Seeking a thrill

After reading in one genre for a while, I often seek a “palate cleanser” by consciously choosing from another. Since I just finished about 2200 pages of epic anthropological science fiction, I decided to turn to something fast-paced and psychologically thrilling, and checked out two books by

B. A. Paris.

The first was The Breakdown, and the title is definitely a double entendre. Cass is driving home from a last-day-of-the-semester party with her colleagues. It’s “a dark and stormy night,” and she’s in a hurry to get home, so even though her husband, Matthew, has repeatedly pled with her not to use the shortcut through the woods, Cass decides to risk it. She sees another car, pulled into a turnout at the side of the road, with a woman sitting in it. She passes the car, then stops and looks back to see if the woman needs assistance, but the woman neither moves from the car nor signals Cass by honking or flashing her lights. It’s raining so hard (and is in such an isolated, creepy location) that Cass doesn’t want to get out of her own car, but she figures that if the woman’s car had broken down, she would have signaled in some way, so she continues her drive home, planning to call someone for her when she gets there. But something happens to put it out of her mind, and she doesn’t make the call.

The first was The Breakdown, and the title is definitely a double entendre. Cass is driving home from a last-day-of-the-semester party with her colleagues. It’s “a dark and stormy night,” and she’s in a hurry to get home, so even though her husband, Matthew, has repeatedly pled with her not to use the shortcut through the woods, Cass decides to risk it. She sees another car, pulled into a turnout at the side of the road, with a woman sitting in it. She passes the car, then stops and looks back to see if the woman needs assistance, but the woman neither moves from the car nor signals Cass by honking or flashing her lights. It’s raining so hard (and is in such an isolated, creepy location) that Cass doesn’t want to get out of her own car, but she figures that if the woman’s car had broken down, she would have signaled in some way, so she continues her drive home, planning to call someone for her when she gets there. But something happens to put it out of her mind, and she doesn’t make the call.

Next morning on the news, she learns that the woman was murdered. Cass can’t seem to overcome her guilt, and it’s compounded by the fact that she doesn’t want to tell anyone (including the police), for fear of incurring scorn and blame, or even suspicion. If only she had stopped, if only she had called, the woman might still be alive.

In the following days, Cass grows increasingly distraught, and begins to exhibit signs of her stress by forgetting things—some small, some important. Compounding her distress is the thought that perhaps she is exhibiting the signs of early onset dementia, which is the disease to which she recently lost her mother. Then the house phone starts ringing every morning after her husband has left for work, but there’s nothing but silence on the other end. Cass starts to believe that someone knows she passed the victim’s car the night of the storm. Perhaps they think she saw something she didn’t. Are they watching her? Stalking her? As her memory grows worse and evidence mounts up that there’s definitely a problem, Cass doesn’t know what to do or whom to trust.

The suspense in this book builds nicely. The author knows just when to deal out bits of information about the other people in Cass’s life—her colleague, John, her best friend, Rachel, her husband, Matthew, as well as more peripheral contacts—to send the reader down some right and some wrong tracks in their suspicions about what’s going on. Like any good thriller, there is a twist you don’t quite see coming that puts the entire story on a different footing and begins to solve the mystery while leaving the most shocking bits for last.

I enjoyed this book so much that I decided to go back for more, and picked up Paris’s book Bring Me Back. This one has a before-and-after component to it, beginning with the traumatic night that Finn lost Layla. The two young lovers were driving home late at night from a ski holiday; Finn stopped at a lay-by to use the bathroom, and when he returned to the car, Layla had disappeared. Or at least, that’s how he told the story to the police; there may have been a few details he left out.

I enjoyed this book so much that I decided to go back for more, and picked up Paris’s book Bring Me Back. This one has a before-and-after component to it, beginning with the traumatic night that Finn lost Layla. The two young lovers were driving home late at night from a ski holiday; Finn stopped at a lay-by to use the bathroom, and when he returned to the car, Layla had disappeared. Or at least, that’s how he told the story to the police; there may have been a few details he left out.

The book picks up 12 years later with Finn living with Layla’s sister, Ellen. After a few stagnant years unable to adjust to the loss of Layla, Finn meets Ellen at a memorial service suggested by Tony, the detective who, during the lengthy investigation, has become a friend. Finn and Ellen take mutual comfort from shared grief and a certain sense of familiarity, and begin to spend time getting to know one another. Now they have been living together for nearly a year, and have imminent plans to wed.

Then Tony calls Finn to tell him that an old neighbor of theirs swears he spotted Layla in the street near the cottage where they lived. Finn’s heart leaps, and he realizes that while he loves Ellen, if Layla were actually alive…the possibilities are troubling. While he assumes that the old man who claims he saw her could have made a mistake, he has no explanation for the Russian doll that appears at his and Ellen’s house, an exact replica of one Ellen lost as a child and always believed that Layla had stolen. And what about the leading emails he begins to receive from a stranger?

Finn keeps most of these events and clues from Ellen, hoping to sort things out on his own. If Layla is still alive, though, why hasn’t she just turned up? What could she want? What is the purpose of this game?

This one was more of a mixed bag for me than The Breakdown; a little more predictable in some moments, a little more clichéd. But I have to say that it was a compulsive read, and despite the ridiculous behavior of some of its characters, I continued to want to know what was going to happen until the very end, which is fittingly climactic. It’s definitely a page-turner that would make you a good beach read, if this is your kind of book! Paris knows how to draw a picture of life that is bright and shiny on the surface but dark and murky underneath, and to dole out glimpses of the latter in tantalizing servings.

From what everyone says on Goodreads, Paris’s most interesting book is still to come: Behind Closed Doors is her debut novel and received many votes in Goodreads’ best debut novel and best mystery/thriller categories. All copies are backed up with holds at the library right now (always a good, though frustrating, sign), so I have put it on my list. The author also has a new book expected to be released in January, 2020.

Cross-cultural sci fi

I’ve just gone on a reading odyssey not quite as lengthy or labyrinthine as Game of Thrones, but definitely of a complexity that would deter some readers! It’s a series containing four books, each of the first three coming in at around 500 pages, and culminating in a fourth book with a staggering 752! The series, by Kate Elliott, begins with Jaran. I had read Kate Elliott once before when I took a look at her young adult series that begins with The Court of Fives. I liked that one well enough to give it four stars on Goodreads, but not well enough to keep reading the rest of the series. But in my comments, one thing I mentioned that I did enjoy was the portrayal of the societal relations between the conquerors and the oppressed.

That turned out to be something that Elliott does even better in her adult novels, and I was immediately hooked by the deeply complex interrelationship of all the players on the board of this science fiction saga. My response to the first book was that it reminded me of a couple of Ursula K. LeGuin’s Hainish books (and I can’t pay a higher compliment than that). Similar to Rocannon’s World and The Left Hand of Darkness, it’s an anthropological science fiction story, with overlapping alien races who may know about each other but don’t know each other. It’s old school, and yet it’s fresh, and I enjoyed and was engaged by the way it unfolded.

That turned out to be something that Elliott does even better in her adult novels, and I was immediately hooked by the deeply complex interrelationship of all the players on the board of this science fiction saga. My response to the first book was that it reminded me of a couple of Ursula K. LeGuin’s Hainish books (and I can’t pay a higher compliment than that). Similar to Rocannon’s World and The Left Hand of Darkness, it’s an anthropological science fiction story, with overlapping alien races who may know about each other but don’t know each other. It’s old school, and yet it’s fresh, and I enjoyed and was engaged by the way it unfolded.

In the first book, we learn that Earth has been subsumed into a vast galactic empire ruled by the alien Chapalii. At one point a human, Charles Soerensen, led a failed rebellion against their dominance, but rather than punishing him, the Chapalii inexplicably made him a “duke” of their kingdom and gave him dominion over an interdicted planet, Rhui. (What it means that the planet is interdicted: The native peoples are prohibited from knowing about space travel, alien or human technology, or anything that is beyond the development of their existing culture.)

On Rhui, there are two types of people, the jaran and the khaja. Khaja is actually a jaran word for “not jaran,” otherwise designated by the jaran peoples as “barbarians.” The jaran are akin to the Romany people of Earth, in that they are nomadic, dwelling in tents and moving from place to place according to whim and affected only by weather and pasture. They are matrilineal, with female etsanas of twelve tribes deciding what’s best for the people, but the women work in a fairly equal partnership with men, who are the warlike, saber-wearing, horseback-riding element of the tribes. They are proud, romantic, mostly illiterate but nonetheless intelligent people with an oral tradition and an elaborate history. And under the leadership of the charismatic and visionary Ilya Bakhtiian, they have recently grown larger aspirations and are in the process of conquering the khaja within their realm of influence.

On Rhui, there are two types of people, the jaran and the khaja. Khaja is actually a jaran word for “not jaran,” otherwise designated by the jaran peoples as “barbarians.” The jaran are akin to the Romany people of Earth, in that they are nomadic, dwelling in tents and moving from place to place according to whim and affected only by weather and pasture. They are matrilineal, with female etsanas of twelve tribes deciding what’s best for the people, but the women work in a fairly equal partnership with men, who are the warlike, saber-wearing, horseback-riding element of the tribes. They are proud, romantic, mostly illiterate but nonetheless intelligent people with an oral tradition and an elaborate history. And under the leadership of the charismatic and visionary Ilya Bakhtiian, they have recently grown larger aspirations and are in the process of conquering the khaja within their realm of influence.

The khaja are all the peoples on Rhui who do not follow in this nomadic tradition—those who have settled down into city-states or kingdoms and jealously guard their land for their own people, who speak various local dialects and are unwelcoming to strangers. Their lifestyle differs markedly from that of the jaran, not just because they are not nomadic, but because they follow a more traditional pattern of patrilineal societies in which women have few rights and are treated as chattel. This includes those groups spread out across the landscape of Rhui and also the inhabitants of the city of Jeds, which is the secret stronghold of Charles Soerensen, the aforementioned duke of the planet, known in Jeds as the Prince of Jeds. This city is the de facto capitol of the planet, where there are schools and universities, a library, and supposedly more “civilized” inhabitants, although under their thin veneer of culture, they also subscribe to the unequal treatment of men and women.

The people of Earth associated with Soerensen cautiously visit and explore the planet in various ways, while maintaining a cover as locals. The Chapalii are supposedly forbidden by the interdiction from traveling to Rhui at all, but as the first book opens, we discover they are not all sticking to this contract.

Charles Soerensen’s heir to the “throne” of Jeds (and actually to all his holdings on all planets) is his sister, Tess. She is young, just graduated from university, and is uncertain of the role she wishes to play in Charles’s complex agenda. She is also suffering from a broken heart, and feeling rebellious. So she sneaks aboard a shuttle bound for Rhui, intending to go to Jeds and buy herself a little time to think; but because the Chapalii on her ship are involved in an illegal operation, she ends up getting dumped somewhere out in the wilds, and is picked up after a week of wandering by the leader of the jaran warriors.

Tess decides that she will remain with the jaran people, immersing herself in their society, as the perfect cover for attempting to solve the Chapalii smuggling scheme that put her there on the planet. What she doesn’t reckon with is her seduction by the warmth and inclusiveness of their lifestyle, and her growing feelings for their leader, Ilya Bakhtiian (and his for her).

Whew! That’s a long and complex introduction to an equally elaborate and convoluted story, but if it sounds like something you’d like, definitely invest the time. With each book more conflicts arise, more truths (about each of the peoples depicted) become apparent, and more investment in the future fates of all takes place. And while we do eventually reach an ending that is satisfactory, the potential is there for more about the individuals and the cultures involved, should Elliott ever decide to revisit them. I can’t help hoping that someday she will!

The four books are as pictured above: Jaran, An Earthly Crown, His Conquering Sword, and The Law of Becoming. Don’t be put off by the covers (dated looking and unfortunately not great to begin with); two of the four books are out of print at this time anyway. But this could be considered a good thing: Who has room on their bookshelves for four more 500+-page books? Do as I did and buy them as a four-book set on Kindle. If you’re not sure you want to read the whole series, you can get each book individually for the Kindle, but why spend the extra money? I checked out the first one from the library, and then got tired of being on the holds list for the other three and bought the set.

If you have ever had a romantic dream of wandering on horseback with the Travelers; if you have ever wondered how a matrilineal society might work; if you have ever wondered if there are, indeed, aliens among us; this is the series for you. (And do check out the Hainish novels of Ursula K. Le Guin as well!)

The power of flowers

Because of an extraordinary amount of rain and snow this year, many parts of the country (mine included) have had a particularly colorful spring when it comes to both wildflower superblooms and the overflowing roses, peonies, and daffodils in cultivated gardens. Observing this bounty has caused me to take a look at some books, both fiction and nonfiction, that deal not only with the appearance but also with the language of flowers.

Because of an extraordinary amount of rain and snow this year, many parts of the country (mine included) have had a particularly colorful spring when it comes to both wildflower superblooms and the overflowing roses, peonies, and daffodils in cultivated gardens. Observing this bounty has caused me to take a look at some books, both fiction and nonfiction, that deal not only with the appearance but also with the language of flowers.

Although flowers and other plants have had symbolic significance for centuries, the full blossoming, if you will, of the use of flowers as symbols for emotions was in the approximate 75-year span of the Victorian Era in England. Restrictive social conventions prohibited direct expression through conversation between those whose interests were loverlike, so whatever was deemed unacceptable by etiquette to share openly was encoded in the giving of particular flowers or combinations of flowers to convey specific meanings. This practice became so commonplace that the language of flowers was christened “floriography.” The practice has also captured the imagination of various authors, who have used it as a vehicle to tell their stories. Among them:

The Language of Flowers,

The Language of Flowers,

by Vanessa Diffenbaugh

From the title, you’d think this book would be soft and romantic, but it’s not at all. The main character, Victoria, is an 18-year-old who has just aged out of the foster care system. She has no friends, no family, no history, no prospects, and no skills, and soon she is homeless. Once she had a foster parent who taught her the language of flowers (i.e., asters = patience, red roses = love, etc.), and since she left that home, she has pursued her knowledge further. Based on this, she finds a florist willing to give her some under-the-table work, and creates for herself a small, regular life—for awhile. The book is told in alternating chapters between the one good foster home she was in at age 10 and her present existence, and the level of tension maintained as you wait to find out what happened that brought her to her current fix keeps you eagerly reading. The protagonist is engaging despite herself, and you don’t know whether you feel sorry for her or want to shake her. It’s a poignant story, and although Victoria isn’t always a likeable character, her courage is inspiring.

Forget-Her-Nots, by Amy Brecount White

Forget-Her-Nots, by Amy Brecount White

While researching the Victorian language of flowers for a school project, 14-year-old Laurel discovers that the bouquets she creates have peculiar effects on people. Her mother hinted at an ancient family secret, and Laurel suspects it has something to do with her new-found talent, but her mom was never able to share either the gift or its use with Laurel. Unfortunately, Laurel uses this talent to meddle, and a string of incidents that involve the misuse of flowers threaten to mess significantly with everyone’s prom night experience. Clever, fun, and informative, too. (Young Adult fiction.)

The Art of Arranging Flowers, by Lynne Branard

The Art of Arranging Flowers, by Lynne Branard

Ruby Jewell grew up in a harsh environment, her only comfort being her close relationship with her sister, Daisy. Daisy’s death when Ruby was in her early 20s was devastating as well as life altering. Instead of pursuing her studies to become a lawyer, Ruby just wanted to curl up and die, too. It was the flowers that saved her. For 20 years now, Ruby has created floral arrangements at her shop in the small town of Creekside. With a few words from a customer, she knows just what flowers to use to help kindle a romance or heal a broken heart. However, Ruby has a barrier around her own heart and is determined that she will not allow it to be broken. It takes an extraordinary group of people to bring Ruby out from behind her wall.

If reading any or all of these causes you to be intrigued by the background these authors used to create their floral fantasies, you can read about Victorian identification in…

Kate Greenaway’s Language of Flowers

Kate Greenaway’s Language of Flowers

This is a charming reproduction of a rare volume by a 19th-century illustrator that includes a full-color illustrated list of more than 200 plants and their supposed meanings: tulip = fame; blue violet = faithfulness, etc.

And if you feel further inspired, you can read some germane nonfiction delving into the scientific significance of blooms:

The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s Eye View of the World,

The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s Eye View of the World,

by Michael Pollan

Michael Pollan has a vision in his garden that leads him to question the interrelationship between humans and plants. He postulates that the plant species humans have nurtured over the past 10,000 years may have benefited as much from their association with us as we have from ours with them. He decides to investigate four plants—apples, tulips, potatoes, and marijuana—and he digs into history, anecdote, and personal revelation to do so. It’s entertaining, philosophical, and smart.

The Reason for Flowers: Their History, Culture,

The Reason for Flowers: Their History, Culture,

Biology, and How They Change Our Lives,

by Stephen L. Buchmann

This is a comprehensive examination of the roles flowers play in the production of our foods, spices, medicines, and perfumes. Buchmann also goes into the cultural history of flowers, examining everything from myths and legends, decor, poetry, and esthetics to their basis for various global industries. From the flowers to the pollinators to the people who pursue the many intertwined careers sparked by these natural wonders, Buchmann inquires about it all. A fascinating volume, liberally illustrated.

If you want more, there is a 17-book list on Goodreads on the subject of floriography.

Here’s hoping your next tussy-mussy conveys the emotions you desire!

Superheroes / Antiheroes

If Marvel movies about superheroes and evil geniuses haven’t yet palled for you,

If Marvel movies about superheroes and evil geniuses haven’t yet palled for you,

there is a young adult novel you might want to try: Brandon Sanderson’s Steelheart. It doesn’t feel like a book written for teenagers, but more like one written for anyone who enjoys stories in which villains take over the world and heroes rise up to fight them.

The premise of Steelheart is that our world has been changed forever by an event that everyone calls Calamity. There aren’t many specifics about the event; there was a big burst of light in the sky, and then afterwards, some of the population developed superpowers. But with the acquisition of great gifts came a lust for power and domination, and the Epics, as they’re called, turned into monsters, wreaking havoc on the portion of humanity that stayed human. They fight amongst themselves for ascendency, destroying infrastructure and driving people underground or enslaving them for their purposes. Many parts of the world have been turned to wasteland, and even the cities that have been preserved by those Epics who wish to rule a cooperative populace are no Eden. People are increasingly unable to remember the good old days, and only hope for such basic amenities as power, clean water, and somewhere

dry to sleep.

The protagonist of the book is David, who is now 18 years old, but had his major run-in with an Epic 10 years ago, when he was eight. At that time (soon after Calamity), some humans, including David’s father, still believed that some of the Epics would turn out to be good, and would become superheroes to defend humanity from the others. But David’s father’s faith was shown to be misplaced, and David has spent the 10 years since his father’s death at the hand of the Epic Steelheart plotting his revenge.

A big part of his plan is to find a group of humans called Reckoners, an underground organization that studies the Epics, finds their weaknesses, and assassinates them. He has tracked the activities of the Reckoners with almost as much attention as he has given to the quirks and skills of the various Epics, and now he is in position to try to make contact and insinuate himself into this band of resistance fighters. And he has a secret that he thinks will gain him a welcome: He is perhaps the only human who has ever seen Steelheart bleed.

There are two sequels to this book: Firefight, and Calamity. Immerse yourself in the world of Epics and Reckoners!

By the way, if this kind of fiction makes you happy, there are a few other titles you will definitely want to try: Carrie Vaughn’s books After the Golden Age and Dreams of the Golden Age; and V. E. Schwab’s books Vicious andVengeful. My review of the books by Schwab is here.

Cheese and crackers

I’m not much of a nonfiction reader—I’m almost never in the mood to tackle some massive tome that tells me everything I (or anyone) ever wanted to know about a particular subject. But sometimes I like to graze a little. You know those days when you don’t want the lunch entree with the salad or fries alongside your giant sandwich, you just feel like making a snack plate with some crackers and cheese, maybe a pickle or some olives, and following up with a cookie? On those reading days, I seek out the essay.

There are many books of essays out there, and they encompass every topic under the sun. Some are serious, some are humorous. Some are lyrical and poetic, others are stark and matter-of-fact. Many writers of longer fiction and nonfiction also have thoughts that don’t extend to an entire novel or treatise but demand to be expressed, so they collect these short nuggets of thought and when they have enough to share, they publish them as books of essays.

One essayist who is a favorite of mine is multiple award-winning science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin. The things I enjoy about her science fiction–that it is rooted in philosophy and ethics and deals with controversial topics–are also what I enjoy about her essays. But they are not all super serious; in her book The Wave in the Mind, she ranges from literary criticism to anthropology to the power of the imagination, and then dips into thoughts on aging, on being a woman, and on libraries. An eclectic but thoroughly engaging collection.

One essayist who is a favorite of mine is multiple award-winning science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin. The things I enjoy about her science fiction–that it is rooted in philosophy and ethics and deals with controversial topics–are also what I enjoy about her essays. But they are not all super serious; in her book The Wave in the Mind, she ranges from literary criticism to anthropology to the power of the imagination, and then dips into thoughts on aging, on being a woman, and on libraries. An eclectic but thoroughly engaging collection.

Another interesting essayist whose writings I enjoy is the Wiccan leader, ecofeminist, permaculture instructor, and novelist Starhawk. She has written three books of essays, but is probably most well known for Dreaming the Dark: Magic, Sex and Politics, which she wrote almost 20 years ago but which still resonates today. The book is political theory grounded in intuitive terms, an examination of hierarchies as structures of estrangement and the consideration of the collective theory of organization as an alternative. If you are a person who is put off by, as one reviewer called it, “hippy dippyness,” you may not enjoy the terms in which she couches her political philosophy; but she has much to share about organizing and empowerment, topics that are currently relevant to many.

Another interesting essayist whose writings I enjoy is the Wiccan leader, ecofeminist, permaculture instructor, and novelist Starhawk. She has written three books of essays, but is probably most well known for Dreaming the Dark: Magic, Sex and Politics, which she wrote almost 20 years ago but which still resonates today. The book is political theory grounded in intuitive terms, an examination of hierarchies as structures of estrangement and the consideration of the collective theory of organization as an alternative. If you are a person who is put off by, as one reviewer called it, “hippy dippyness,” you may not enjoy the terms in which she couches her political philosophy; but she has much to share about organizing and empowerment, topics that are currently relevant to many.

When you want wryly funny stories of everyday life, Annabelle Gurwitch is a good choice. After being fired by her idol, Woody Allen, she began back in 2005 by collecting other people’s stories about being fired from a job, and parlayed those into a gig on NPR, a live stand-up show with friends in L.A. and New York, a documentary film and, finally, a book of essays called Fired! Tales of the Canned, Canceled, Downsized, and Dismissed.

When you want wryly funny stories of everyday life, Annabelle Gurwitch is a good choice. After being fired by her idol, Woody Allen, she began back in 2005 by collecting other people’s stories about being fired from a job, and parlayed those into a gig on NPR, a live stand-up show with friends in L.A. and New York, a documentary film and, finally, a book of essays called Fired! Tales of the Canned, Canceled, Downsized, and Dismissed.

She followed those up with I See You Made An Effort, her humorous essays about aging towards 50, and Wherever You Go, There They Are, stories about her family of “scam artists and hucksters.” Conversational, sarcastic, but also sweet, Gurwitch hits a common human note that many will enjoy.

She followed those up with I See You Made An Effort, her humorous essays about aging towards 50, and Wherever You Go, There They Are, stories about her family of “scam artists and hucksters.” Conversational, sarcastic, but also sweet, Gurwitch hits a common human note that many will enjoy.

Renowned poet Mary Oliver is best known for her award-winning poetry, in which she celebrates all aspects of the natural world in lyrical yet concise verse. But Oliver was also an essayist, and although she preferred to write poetry, citing prose as “the softened, fleshy story, while poetry remains the stark revelation in writing,” her essays are also a treat. Since she generally mixes essays with poetry in all her books, check one out and you can experience both! Her essays are primarily contained within Long Life and Upstream.

Renowned poet Mary Oliver is best known for her award-winning poetry, in which she celebrates all aspects of the natural world in lyrical yet concise verse. But Oliver was also an essayist, and although she preferred to write poetry, citing prose as “the softened, fleshy story, while poetry remains the stark revelation in writing,” her essays are also a treat. Since she generally mixes essays with poetry in all her books, check one out and you can experience both! Her essays are primarily contained within Long Life and Upstream.

In 2003, author and editor Dave Eggers started publishing a magazine called Believer, an eclectic mix of pop culture and literature. Essays originally published in that magazine were later collected into two volumes, Read Hard, and Read Harder, a delightful collection of the profound and the absurd by such writers as Jonathan Lethem, Nick Hornby, Lev Grossman, and Susan Straight.

In 2003, author and editor Dave Eggers started publishing a magazine called Believer, an eclectic mix of pop culture and literature. Essays originally published in that magazine were later collected into two volumes, Read Hard, and Read Harder, a delightful collection of the profound and the absurd by such writers as Jonathan Lethem, Nick Hornby, Lev Grossman, and Susan Straight.

It’s bittersweet to realize the power and poignancy of the essays in The Opposite of Loneliness, by Marina Keegan, because this is the only book we will ever have from her; she died in a car crash five days after graduating from Yale University, just weeks away from taking a position at the New Yorker. But her essays live on, defining and discussing the struggle we humans face as we try to figure out who we are or want to be, and how that will be expressed in our lives. Her best known essay is “Even Artichokes Have Doubts,” about the odd career aspirations of her fellow classmates after Yale.

It’s bittersweet to realize the power and poignancy of the essays in The Opposite of Loneliness, by Marina Keegan, because this is the only book we will ever have from her; she died in a car crash five days after graduating from Yale University, just weeks away from taking a position at the New Yorker. But her essays live on, defining and discussing the struggle we humans face as we try to figure out who we are or want to be, and how that will be expressed in our lives. Her best known essay is “Even Artichokes Have Doubts,” about the odd career aspirations of her fellow classmates after Yale.

In Utopia is Creepy, and Other Provocations, Nicholas Car, author of The Shallows (“Is Google Making Us Stupid?”), discusses the various social aspects of technology, looking with an educated and somewhat jaundiced eye at everything from Wikipedia to Snapchat. The essays are interesting for both inveterate tech lovers and those who fervently wish that Tim Berners-Lee had never invented the World Wide Web. His final conclusion? “Resistance is never futile.” See what you think.

In Utopia is Creepy, and Other Provocations, Nicholas Car, author of The Shallows (“Is Google Making Us Stupid?”), discusses the various social aspects of technology, looking with an educated and somewhat jaundiced eye at everything from Wikipedia to Snapchat. The essays are interesting for both inveterate tech lovers and those who fervently wish that Tim Berners-Lee had never invented the World Wide Web. His final conclusion? “Resistance is never futile.” See what you think.

There are hundreds of collections of essays out there in the world—do you have a favorite?

New from Heller

I never bypass the chance to read a novel by Peter Heller. I love that I never know what to expect—each book is so different from the one before, but all are gripping; his prose is both spare and lush in its evocations; and on top of that, the guy can tell a story. Once having read both The Painter and The Dog Stars, I would have been hard pressed to choose a favorite between them, and although I liked Celine less, it was, again, such a departure from previous works that both its characters and its mystery intrigued me.

His new book, The River, is similarly powerful. The sense of uneasiness evoked from the very first page builds to a cascade of climactic moments, each overpowering the previous one, until you wash into the ebb tide of the epilogue and realize you’ve been holding your breath for a good part of the book.

His new book, The River, is similarly powerful. The sense of uneasiness evoked from the very first page builds to a cascade of climactic moments, each overpowering the previous one, until you wash into the ebb tide of the epilogue and realize you’ve been holding your breath for a good part of the book.

Two college friends, Dartmouth classmates Jack and Wynn, are taking a much-dreamed-of trip together, setting aside a few weeks to canoe a series of lakes into a northern-flowing river up into Canada. Jack, who was raised on a ranch in Colorado, is the more experienced of the two at camping and hunting, but Wynn, a gentle giant from rural Vermont, has his share of skills. They plan a leisurely trip of trout fishing, blueberry picking, and a slow trek through a route that alternates between smooth, flat water idyllic for paddling and rapids that must either be run or portaged around.

All of this changes one afternoon halfway through the trip, when the two climb a hill and see the glow of a massive forest fire about 25 miles off but clearly headed directly across their path. The lakes up until now have been completely empty of humans, and the two boys have enjoyed the cry of the loons and the spectacle of moose, bear, and other wildlife, but as they paddle upstream with new urgency, they encounter first a pair of men, drunk on whiskey and lolling in their campsite with no awareness of their peril, and then, as fog drops down and obscures the shore, they hear the voices of a man and woman, arguing passionately, their voices bouncing across the water. They warn the men about the fire, but can’t catch a glimpse of the contentious couple, and paddle on to their next campsite.

The next day, burdened with a sense of guilt for not searching harder, Jack and Wynn agree to turn back and warn the couple, if they can be found. This turns out to be a fateful decision that burdens them for the rest of their trip with unexpected responsibilities, dangers, and crises over and above the dreaded wildfire, which approaches ever closer.

Heller always delivers on atmosphere, and even if you have never camped out, paddled a canoe, or caught a fish, you are right there with his characters on the bank of the lakes and river, looking at the stars, watching the raptors in their nests at the tops of the tallest trees, or reeling in a line with a brown trout on the hook. The reader also gets quickly inside the heads of both protagonists, as well as tapping into the quiet and solid friendship between the two, which nonetheless becomes strained as events ramp up to catastrophe and their differing temperaments emerge.

As with his other books, I read this one in a day and a half, only deterred from one continuous sit-down by a traitorously depleted battery in my Kindle. In an interview for Bookpage, Heller said that he writes…

“…a thousand words a day, every day, and I always stop in the middle of a scene or a compelling train of thought. Most writers I know write through a scene. But if you think about it, that’s stopping at a transition, a double-return, white space. That’s what you face the next morning; it’s almost like starting the book fresh. If you stop in the middle, you can’t wait to continue the next day.”

That same sense of urgency pervades me as I read any of his books.

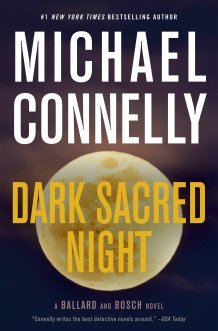

A reliable, enjoyable read

I just picked up Michael Connelly’s latest, Dark Sacred Night, which is a combo novel featuring both Harry Bosch (his 21st outing) and Renee Ballard (#2 for her) in the Bosch “universe” of 31 books. I have been nervous, for the past few volumes, that with Harry truly getting beyond the age of a comeback, Connelly’s franchise would dwindle. Although I am a fan, for instance, of John Lescroart’s Dismas Hardy series, I have been vocal about my disappointment in those books in which he chooses one of his other characters as the lead, and I wasn’t quite sure, with the first Renee Ballard book, that Connelly wasn’t going to go the same way, even though Renee’s character sketch was intriguing. (She has no permanent home but that of her Gran’s up in Ventura, and sleeps between shifts in a tent on the beach in Venice, with her dog to guard her, and her surfboard and a casual relationship with a lifeguard to keep her entertained.)

Fortunately, with his choice to bring the two detectives together for Renee’s next adventure, Connelly both solidified her character further and gave us something to compare and contrast between the way the old veteran and the young fanatic go after their cases. Harry recognizes by the end of this joint endeavor that Renee has that same certain something—the gleam in the eye, the doggedness of the pursuit, the dedication of the purist—that has kept Harry going through multiple separations from the LAPD, private consulting, and now as a part-time temporary guy at San Fernando’s tiny police department…and so do we, the readers. So while I had my doubts, this book made me much more confident that Connelly can pull off this changing of the guard, particularly by using these transitional novels.

After Ballard’s run-in with a superior officer (a sexual harassment incident in which she was the target) in her book #1, she was shunted off to “the late show” (the graveyard shift) at Hollywood’s detective bureau. And although it’s not been great for her career, she has decided that there are many advantages to this shift, including greater autonomy both at work and in her free time, and the opportunity (in the occasional downtime of the wee hours) to pursue cold cases. One night she returns to the deserted detectives’ bureau after having rolled out on a case that might have been homicide but turned out to be accidental death, only to find a stranger going through filing cabinets that she would have sworn were locked when she left the office. After interrupting him and essentially kicking him out, she becomes curious about who this guy is and why and how he got access, and goes on a fact-finding enquiry about Hieronymus (Harry) Bosch.

After Ballard’s run-in with a superior officer (a sexual harassment incident in which she was the target) in her book #1, she was shunted off to “the late show” (the graveyard shift) at Hollywood’s detective bureau. And although it’s not been great for her career, she has decided that there are many advantages to this shift, including greater autonomy both at work and in her free time, and the opportunity (in the occasional downtime of the wee hours) to pursue cold cases. One night she returns to the deserted detectives’ bureau after having rolled out on a case that might have been homicide but turned out to be accidental death, only to find a stranger going through filing cabinets that she would have sworn were locked when she left the office. After interrupting him and essentially kicking him out, she becomes curious about who this guy is and why and how he got access, and goes on a fact-finding enquiry about Hieronymus (Harry) Bosch.

When she finds out that he’s pursuing a cold case and herself becomes intrigued by it, she offers to work with him, in her spare time, to solve it. Harry’s not sure he needs the help or wants a partner (when has he ever?), but since having an in-house buddy at the LAPD ensures him access to stuff he couldn’t get at on his own, he agrees.

The case is nine years cold, the murder of 15-year-old runaway Daisy Clayton, brutalized and left in a dumpster, and Harry has a personal interest in the case; he has met and befriended Daisy’s mother, Elizabeth, and helped her to get clean from an opioid addiction she fell into after her daughter died. Harry has promised Elizabeth that he won’t let go of Daisy’s case until he solves it and gives her at least that much closure. Renee Ballard, being generally inclined towards solving cases involving victimized women, is immediately intrigued by the details of Daisy’s story, and she and Harry trade off on tracking down leads, sources, and suspects before and after Ballard’s late-night shifts and Harry’s part-time day job, sometimes working together and sometimes tag-teaming one another. Being true to actual police work, this case isn’t the only thing keeping the two detectives busy, and the book is an action-packed amalgam of multiple story lines.

The book is told in the third person, but from two viewpoints, following each character individually and also when they work together, and it’s an effective back-and-forth reflecting all the fascinating details of police procedurals at which Connelly excels.

At the end of the book, a tentative suggestion is made by one detective to the other that perhaps they could work together again in the future; I have a feeling that offer will be taken up in Bosch 22, Ballard 3, and Universe 32! (Or maybe it will simply be called

B&B #2.)