Odd mystery series

I was in between loans from the library a few days back, so I browsed the books on my Kindle to see what on there was still unread, or what I might want to reread, and I happened across Charlaine Harris’s Lily Bard mysteries. They are oddly named, and they are oddball murder mysteries—strangely engaging, given their dark tone. They would probably fall under the category of “cozy” mysteries, because they take place in a small town and the lead character isn’t a police officer or a detective, but they are, in fact, the antithesis of cozy in their theme! All five books have the name “Shakespeare” in the title, beginning with Shakespeare’s Landlord, and it’s confusing until you figure out that the protagonist, Lily Bard, was picking a town at random to call home and chose Shakespeare, Arkansas, simply because her last name is Bard. I guess there could be worse reasons for choosing to live somewhere…

Anyway, Lily, the center of all the action, is the survivor of an extremely violent and traumatizing episode in her past and, after trying and failing to get back to normal in her home town, where everyone knows what happened to her and is either pitying or prurient, depending, she moved a few times and finally landed in Shakespeare. She keeps strictly to herself: She makes her living by cleaning houses (preferably while her clients are away at work); she works out at the local gym—lifting weights and taking karate classes so that she is strong and self-sufficient; she avoids friendships and entanglements; and she walks the town at night when she can’t sleep.

When the first book opens, Lily has lived in Shakespeare for about three years, and has managed to remain a mystery to most of the town’s inhabitants, even though gossip in a small southern town is pretty pervasive. All that is about to change, however, because one dark night she witnesses a dead body being dumped in the town’s arboretum close to her house, and the murderer is using her trash bin cart to move the body. Even though she tries her best to stay out of it, an anonymous call to the local police chief, who happens to live in the neighboring apartment building, eventually drags her into the limelight. She soon realizes that the only way she’s going to get back to her peaceful existence is to figure out who killed the police chief’s landlord.

Each of the books features a murder, four of the five in the small town that apparently harbors a bunch of violent people below its deceptively peaceful surface presentation. (The fifth takes place back in Lily’s home town when she returns to serve as maid of honor in her sister’s wedding.) And Lily is somehow connected, if only tangentially by her job, her gym, or her therapy group, to all of the victims. This woman has had and continues to have some stunningly bad luck in life. To counterweight some of that, Harris has her meet a guy in book #2, the first person she doesn’t want to kick to the curb after a single encounter in all the years since her tragedy separated her old life from her new. And although the involvement is slow and cautious with many setbacks, the relationship is a true match.

It’s an weird little series, not only because it’s so relentlessly downbeat but because when I read it, I liked it enough to reread it twice! I can’t say what is so engaging about it—most of the inhabitants of the town are none too nice, and Lily herself, although admirable for her stoicism and self-reliance, is about as loveable as a cactus. Still, there’s something vulnerable about the way Harris writes these people that makes you want to know what happens to them, despite yourself.

Have a gander, as they might say in Arkansas, and see if the Lily Bard series is for you.

Chartreuse

I just finished reading The Grey Wolf, Louise Penny’s latest (#19) in her Chief Inspector Armand Gamache series, and I am torn.

On the one hand, I found myself thinking, during the course of the extremely intricate narrative in which both the reader and Gamache himself are unsure who can be trusted, who is in the know, and who is culpable, that I was enjoying a complex plot in which I wasn’t sure, at any moment, what was to happen next, or who was responsible. I have been reading too many suspense or thriller novels recently that had about as much subtlety as a romcom and disappointed my need for intelligent thought. From that standpoint, I appreciated the complexities of The Grey Wolf. I also enjoy Gamache’s philosophical musings about people and life, and his lyrically worded observations of nature. So there were definitely things to like.

On the other hand…

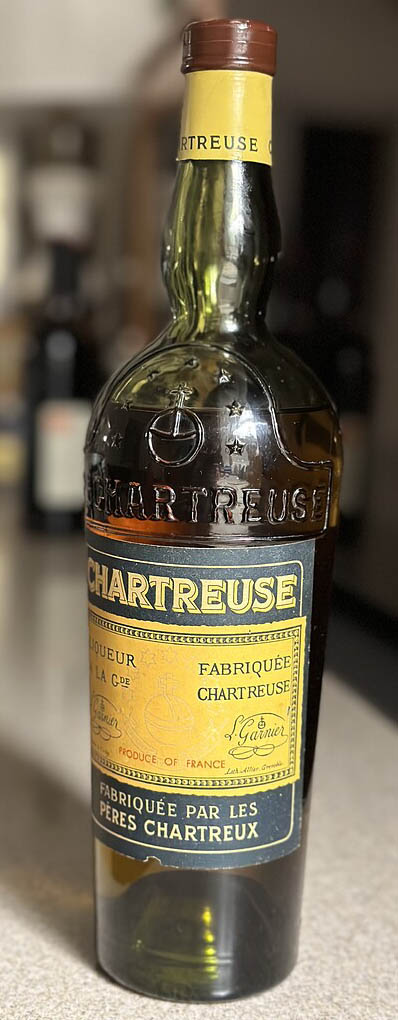

I found myself agreeing with another Goodreads reviewer, who said about this plot, “Penny needs to go back to solving homicides, not national security and international intrigue issues.” It seems like she is making a shift to writing thrillers rather than mysteries. I also agreed with several others who opined that although the plot itself is pretty clear—there is a scheme to poison the drinking water of Montréal by a ruthless person or persons who don’t mind killing anyone who knows anything and/or speaks out—the working out of it, with the jaunts to Washington, D.C., Rome and France, to obscure towns in the wilds of Quebec and to cloistered monasteries whose recipe for a well-known liqueur is another red herring, is overly convoluted and, honestly, somewhat ridiculous. I became skeptical that there was literally no one in the government to trust, other than Gamache’s son-in-law Jean-Guy Beauvoir and his compatriot Isabelle Lacoste (this must be the most corrupt government in Canadian history!) and somewhat bored by the round-and-round nature of clues that led to nothing but more obfuscation.

So…although I am always happy to discover a new Gamache mystery, this one left me more dissatisfied than not.

Also, on a separate topic, am I misremembering, or has Penny rewritten “history”? How is Gamache still in his 50s? I can’t recall the specific book, but I thought he had passed into his 60s in a previous story. And didn’t his godfather, Stephen Horowitz, who is referenced in this book, die in Paris, in All the Devils Are Here? And although I did remember the involvement of Gamache and Beauvoir with the Gilbertine monks from A Beautiful Mystery (book #8), all this back story about this “old adversary” who is now assistant to the deputy prime minister—is my memory so bad that I simply don’t remember that plotline, or WAS there no book and Penny is just making up a shared past for them for The Grey Wolf?

I’m not ready to call it a day on the further tales of Chief Inspector Armand Gamache of the Sûreté du Québec (especially because this book ended on a cliffhanger), but I’m approaching them with less expectation of true love than I used to do.

Learning through fiction

Someone on one of the readers’ pages I frequent on Facebook posted something recently about only wanting to read nonfiction because she “likes to learn while I read.” And it made me think about the fact that I never read nonfiction (since I left school, I can count the number of nonfiction books I have read on two hands), but that I learn many things, nonetheless, from my reading.

One example that I use when people raise an eyebrow in disbelief: A few years ago, one of my friends told me she was suffering greatly from Ménière’s disease, which is “a disorder of the inner ear that can cause vertigo (spinning sensation), tinnitus (ringing or buzzing in the ear), hearing loss, and a feeling of fulness or pressure in the affected ear. It is a chronic condition, meaning it’s long-lasting and can have recurrent episodes of symptoms.” She told me there was no sure-fire treatment and that she simply had to live with it, but that it meant multiple days of lying immobile waiting for the symptoms to go away.

I immediately remembered a scene in Barbara Kingsolver’s novel Prodigal Summer. There is a character in that book, a woman who has a little girl who suffers from extreme vertigo, called BPPV. BPPV is “Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo.” It is a common cause of “a feeling of spinning or dizziness. It’s triggered by changes in head position, especially when rolling over in bed, getting out of bed, or tilting the head. BPPV is caused by loose crystals in the inner ear that move into the wrong part of the balance system.” When the wave of dizziness hits, the book describes how the woman lays the little girl down with her head hanging over the edge of her bed (or, if they are out in public, over her mother’s arm), and then has her do a slow, timed series of movements that alleviate the condition. The action is called the Epley Maneuver. Loose crystals (called otoliths) have become displaced into the posterior canal of the inner ear, which makes the brain think that fluid is moving due to a head turn when it is, in fact, caused by the crystals. Since the fluid is moving even though the head is stationary, it brings on extreme dizziness. The Epley Maneuver attempts to reroute the crystals, moving them out of the canal so that the cause of the dizziness goes away. (Here is a YouTube video that explains the maneuver—if you search it on YouTube, you will find multiple demonstrations. https://youtu.be/o4GV-EbnMfI?si=1lzrDemwCgLayCR-)

In the book, the woman has a neighbor, a curmudgeonly old man with whom she has been feuding over various things for many years. But when he himself has an onset of BPPV, she kindly teaches him the Epley Maneuver.

When my friend told me about her distress and how severely this condition was impacting her day-to-day living, I remembered the scene from Prodigal Summer and shared the technique with her. She tried it and, after repeating it a few times over the next 24 hours, her BPPV subsided. From then on, when she felt it coming on, she would use the maneuver to avoid the onset of the attack.

It should be noted that if you google Ménière’s disease, it will tell you that treatments include diuretics (bad for you) and surgery, and that it’s incurable. I would never have discovered the Epley Maneuver if it hadn’t been for this novel by Kingsolver.

I reflected on this today when I was coming to the end of The Grey Wolf, the latest Armand Gamache mystery by Louise Penny. Armand muses on a quote he heard somewhere that, for me, perfectly epitomized the world we here in the States are living through under our current insane and oligarchic regime. It said,

Do not attribute to malice that which can be explained by stupidity.

It went on to note that there was plenty of malice to go around (yes, there is!), but that it was far outweighed by sheer stupidity. I am constantly reminding myself of this as political events unfold around us, and trying to hold onto the hope that the readers among us will prevail and both malice and stupidity will eventually subside.

Still waiting

I finally picked up Michael Connelly’s latest, The Waiting, which features Detective Renée Ballard, backed up in one of the three plotlines by the retired Harry Bosch and in another by his daughter, Maddy, a fledgling police officer. And my title refers to the feeling that I am regrettably still waiting for this new protagonist to take off and give me the same fondness for Connelly that I have had throughout Harry Bosch’s long and checkered career and also that of Mickey Haller, the Lincoln Lawyer, in that side series.

Alas, after this fourth (fifth?) book featuring Ballard, I’m thinking that once Harry is well and truly no more, I will be letting this series slide off my TBR list. At this point, Ballard feels irretrievable to me; I believe Connelly’s best bet would be to dump her and start fresh with a brand-new protagonist who has absolutely no associations to previous characters (and therefore doesn’t suffer by comparison).

It’s hard to say exactly why I verge on disliking Renée; but it’s more than just that she’s not Harry. As I mentioned in a previous review, I was open to the switch to her quirky, nomadic character in the first book, when she was living on the beach in a tent with her dog and gave almost equal importance to surfing that she did to police work; but once she was integrated into the system, she became almost immediately boring. She has no life, she has no friends (even her relationships with her co-workers being either adversarial or more transactional than comradely), she is constantly reckless on the job but then inexplicably irritated that management doesn’t view her favorably or even benignly, and she’s a terrible dog parent! Honestly, she’s kinda toxic. Harry was also a rule-breaker, but his motivation was almost always clean: It was all for the sake of solving the case, helping the victim, catching the criminal. Ballard, next to him, seems calculated and kind of manipulative; she complains about the politics, but then fully enters into them to get what she wants.

I didn’t love any of the three plot lines in this one either. In the first, Renée’s car is broken into while she’s out on the water before work, and rather than simply report the theft of her wallet, badge, and gun, she decides that it’s a potential career ender (although it wouldn’t have been had she not given her superiors and colleagues reason to be exasperated with her consistently erratic behavior) and involves multiple people in surreptitious plotting and planning to get them back without anyone in power finding out. Even though it leads to a major take-down of dangerous people, it was so shortsighted in its motivation that it irritated me. She brings Harry in on her convoluted plotting to mask her own involvement, then wallows in guilt in case he gets hurt. I think this is one of those reasons for dislike of the character: She can’t herself decide who to be, so as a reader it’s hard to fasten onto some character trait to love.

The second plotline is initially gripping; a cold case that the Open/Unsolved Unit has been exploring via volunteer Colleen’s genealogy and DNA studies yields a familial connection to a serial rapist who terrorized the city for almost five years and then abruptly went inactive 20 years ago, and if the connection is correct, the rapist is a political hot potato. It could be a sensational “win” for the beleaguered unit, but then things take an unexpected (and less interesting) turn and the case is dragged out for the rest of the book only to be resolved quite abruptly in the last 20 pages.

Likewise, the involvement of Officer Madeline Bosch feels contrived, and her personality and participation are so muted that I could have wished this were simply omitted. Perhaps Connelly’s plan is to substitute Maddy for Harry now that Renée isn’t doing so well in the ratings, but if he’s going to do that, he has to get her off “the beat” and into a detective job in a hurry, which means doing some career short-cutting. What better way to achieve that than to have her volunteer for the Open/Unsolved Unit with the specific motive of solving the most notorious cold case in Los Angeles history? Like I said, it felt contrived.

All the other characters in the book, from the captain and the chief to Ballard’s volunteer co-workers to the FBI guys remained essentially cardboard characters, serving only as foils for the main characters, and not great ones.

I’m feeling like a huge curmudgeon—here she goes with another “damning with faint praise” review—but honestly, it’s been so long since an author and a book really knocked my socks off that I’m starting to believe that either they don’t exist or that I have become so hard to please that it will never happen again. I hope neither of those is true. I started this blog to encourage people to read, not to turn them away from books they might potentially enjoy!

Anyway, I’m also hoping Connelly will back himself out of this trajectory and pick a new one, because he’s been a good story-teller with a lot to offer throughout the Bosch and Haller years and I want that to continue. But I don’t think it’s going to happen if he sticks with Ballard.

Reimagining

I just read James, by Percival Everett. Despite being 300 pages, it was a quick read, unlike the story from which it was taken, which took me twice as long to reread. I think there were two reasons for this one going so quickly: One was that it leaned on the presumption that you already knew the original tale and therefore the author gave himself permission to shorthand much of the action and description from that book; the other was that almost the whole story took place in either internal or external dialogue, without a lot of world-building, scene-setting, or exposition.

These things led to an interesting experience if you were hoping to confront this old story from a completely new perspective. I wanted to embrace this book, but I struggled a bit.

The premise that the slaves spoke patois in front of the white “massas” but used the common language when alone seemed a natural outgrowth of their situation; they had to communicate important information with one another without the white people catching on to what was being said, and they had to hide their real personalities behind a façade of ignorance, foolishness, and passivity, so they learned code-switching from childhood. Everett completely enthralled me with this; but then he took it a little too far. I expected the character James to be a bit more than ordinary, given his interactions with Huck and others in the original, but did his life experience really allow him the latitude to become as extraordinary as Everett has written him?

He is painted as an educated man—not just a slave who has learned to read and to speak with a careful use of diction. Would the surreptitious reading sessions in Judge Thatcher’s study in the wee hours really lead to a thorough understanding of the works of Voltaire, Rousseau, and John Locke? Even southern college-educated men of that day were not necessarily cognizant of the intricacies of philosophical thought, so the requirement that we believe it of a man who has had to gain all his education on the sly in stolen moments is a little hard to meet.

This was, to my mind, a central flaw of this book, for the simple reason that we went from perceiving the disguise the original “Jim” presented to the world—the stereotypical shuffle-footed, awkward, ignorant, well-behaved and possibly well-intentioned slave—to yet another disguise for “James”—the cynical, perceptive, erudite man who is playing that character for half his world while laughing about it with the other half. I actually liked that for its dark irony; what I’m trying to say is that there was an opportunity here for us to get to know the real person, but except for some tantalizing and admittedly affecting glimpses here and there, we went from one façade to another. With as much internal dialogue as there was from James, there was nonetheless too little understanding of the man himself. While being able to recognize that he is quick-witted, thoughtful, and compassionate, I didn’t feel that I really understood how he acquired all those positive character traits, because he doesn’t let us in.

The other thing the book thoroughly exhibits is the two-faced nature of slave owners who wish to be regarded as benevolent protectors of their “childlike servants,” but turn on a dime, when challenged, to become brutalists who exult in wielding a belt or raping a child. And again, I found myself applauding the exposure of the stereotypes but wincing at the one-dimensional portrayals—not so much of the slave-owners, but of the slaves! Several other reviewers have noted that the women in this book seem to be present on the page merely to highlight their own ill treatment; they have no agency and almost no personality but are merely offered up as horrifying examples of the results of human ownership. Again, I have no quarrel with exposing the heinousness of the practice, but how much more affecting would the book have been had readers been able to better identify with these women as individuals with personality?

I don’t want to come across as hyper-critical of this book. I admired what he tried to do and was caught up in it while reading it. I am also a fan of his writing style and language, which can be beguilingly beautiful. It actually troubles me to go against the reviewers who gave it unreserved praise (not to mention the National Book Award!). But afterwards, while reflecting on what I had read, I also wished there had been more—more story, more depth of character, more nuance, more exploration. I am curious, now, to read others of his books to see what my reaction to him as a writer might be when not influenced by the rewriting-of-a-classic aspect of this one. I’m sure you’ll hear more about it from me eventually.

The Empyrean “trilogy”

This series by Rebecca Yarros has been hyped a lot. I usually shy away from that, because I have discovered it’s more often than not the kiss of death to my enjoyment. But…dragons. I love dragons. I read all of Anne McCaffrey’s Pern books at least three times. I adore the dragons of Patricia Wrede, Bruce Coville, Diana Wynne Jones, and Angie Sage, and also those in Tolkien’s The Hobbit and Farmer Giles of Ham. I put up with Jane Yolen for the sake of dragons. Dragons gave added value in Ursula LeGuin’s Earthsea books and in the various trilogies by Robin Hobb. One of my favorite series is The Last Dragonslayer and sequels, by Jasper Fforde. I was intrigued by Rachel Hartman’s dragon/human shapeshifters in Seraphina and Shadow Scale. Robin McKinley’s Damar books use dragons as more of an excuse for a story than as a major plot element, but I still loved them. So. I was perhaps predestined to read these.

I will say that I was not initially disappointed by the dragons themselves. They are pretty cool, and the two we get to know more intimately through their association with main character Violet Sorrengail (Tairn and Andarna) have real personality. But there was much less thought put into all the rest of the dragons who appear in the books and, aside from their names being linked as a bonded pair with various characters, they were sadly both interchangeable and underutilized.

As for everything else, well, let’s break it down:

The writing was somewhat pedestrian—way too much exposition, language that was overly ornate but never coming to the point, and modern anachronisms (“for the win” and “shit’s about to get real” are the biggies that come to mind) that took me right out of the fantasy illusion. Sentence structure was awkward. (One reviewer actually counted and said “Yarros used 493 ellipses and 1,089 em-dashes in the 634 pages of Iron Flame.”) Both the meandering plots and the effusive, exclamatory style made me wonder how much power the editor was given over the content of these books (and why it likewise went underutilized).

The character building was good in the first half of the first book, and then disintegrated with each subsequent encounter. The protagonists, Violet and Xaden, had great potential, but knowledge of them stays on a shallow level because the author keeps describing them over and over without adding anything new, and the encounters between them are equally as repetitive. Both the heroism and the villainy become boring, because there’s little depth or explanation. And we might as well go on here to talk about the “romance” between the main characters, because this was an element that made them work even less for me. The first (explicit) physical encounter between them felt hot and daring, but by the time I got through the third book I was cringing and skipping the sex scenes because they were unoriginal replays both physically and verbally.

The secondary characters (Violet’s squad and siblings, the rebels closest to Xaden) had individual quirks that made them lovable or frustrating or inspiring or whatever, but I was disappointed that there was so little growth beyond the naming of that one element that characterized each of them. Much like the dragons, their characters and camaraderie could have been so much more of a feature, had the author cared more, but they were essentially one-dimensional.

The world-building was sloppy. It seemed like the only time it happened was when it was bolstering some plot point, so it became wearisome, for instance, to find out brand-new information well into the second or even third book simply because it was necessary to further the story. The fact that magic dwells only on the main continent, protected by wards, but there are whole archipelagos of islands without it, or that dragons are companions to the people in the warded lands but hated, feared, and targeted by the others would have been enlightening to know halfway through book one, not two-thirds of the way through book two (or later). And as for what magical abilities everybody has, it definitely felt like Yarros was making that up as she went along and needed a Hail Mary to get her out of the situation into which she had written herself. Everything we learned seemed less like a planned surprise and more like a decision in the moment as the author thought of some way to turn the story—oh, did I forget to mention this? Well, let me explain it here for you and then we can move on.

I will also say that since I am not a big fan of romance, maybe “romantasy” wasn’t as appealing to me as it might be to some; but I don’t think that’s really the problem. The problem is the endless, repetitive nature of the supposedly romantic encounters, which is a euphemism for the fact that every time the two protagonists saw each other, it was immediately sexual. Some non-fraught conversation would have been nice. Some peeks into childhood, some sharing of philosophy, a picnic, a book recommendation? Something.

Fourth Wing was good, despite some of these deficits, because we were discovering brand-new information—the challenges of getting into and surviving battle school, the intricacies of bonding with dragons, learning how to navigate the politics of both school and kingdom. It was interesting to learn that Violet had planned and thought she was destined to be a Scholar but was forced, despite her physical frailties (readers said the description of these sounded like she had Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome) and small stature, to choose to be a dragon-riding warrior because her mother was a big-deal commander and wanted all her children to choose that path. The details about Xaden and the other tattoo-marked riders being the children of rebels, basically conscripted into the dragon army to atone for the sins of their (deceased, executed) parents were intriguing. And the physical and mental obstacles Yarros sets up to test the potential riders to prove they could do the job were exciting.

But after the first shocks of a new environment, a new protocol, a forbidden love, the rest seems disappointingly like nothing but reiteration, filler, and false obstacles created to provide constant peaks and valleys in the relationships and the plot without ever taking us much of anywhere new. So (for instance) every time Xaden appears on the page, Violet has to lustfully re-react to his physique, his tattoos, his smoldering expression, his shadow-wielding. Every action or battle scene exists so that brave, impulsive but fragile Violet can be in peril or injured and Xaden can magically turn up to save her, scold her, and have his way with her (after the healers put her back together). And both the action and the storyline depend way too heavily on the life stories of just these two characters. It makes a dull read out of what could have had more significance and nuance.

My biggest beef, however, is that I was ignorant of what was apparently some fairly recent news. This was billed as a trilogy and I was, frankly, delighted to hear that. I wanted to read a series that had a beginning, a middle, and an end within a limited framework. So many fantasies just keep going until they exhaust either their author or their readers, but I thought I had discovered a tale that would be neatly told in three admittedly long but finite books. Nope. I kept reading book #3, at first thinking I should surely be farther along than 37 percent because what was left to say? and then thinking oh, there has to be at least 20 percent more to go because this doesn’t feel anywhere close to wrapping up, and then turning a page to discover, uh-oh, it’s over; WHAT?! I reread the ending of Onyx Storm three times and could make no sense out of it, only to discover (in a footnote on Goodreads on Yarros’s author page) that the rather cryptic close of that book was intentional because…dum dum DUM…there are two more books slated to be published. And after struggling through all the sturm und drang of book three without getting resolution of the central issue in a whopping 527 pages, I was, frankly, pissed off. I think I am done with Rebecca Yarros, despite the dragons. And that’s a big, big deal. Phooey.