Reimagining

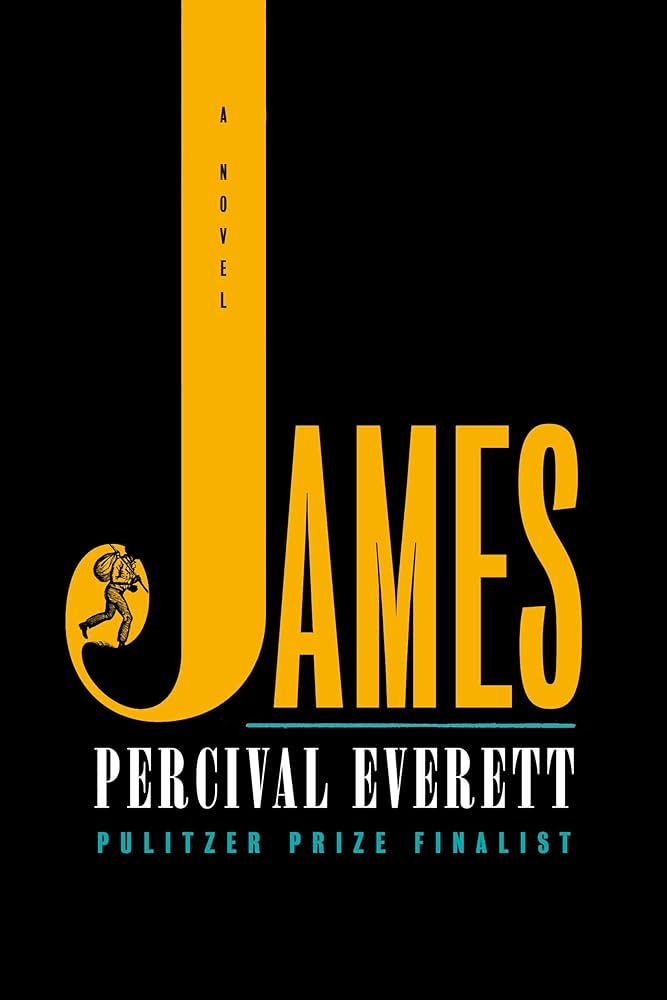

I just read James, by Percival Everett. Despite being 300 pages, it was a quick read, unlike the story from which it was taken, which took me twice as long to reread. I think there were two reasons for this one going so quickly: One was that it leaned on the presumption that you already knew the original tale and therefore the author gave himself permission to shorthand much of the action and description from that book; the other was that almost the whole story took place in either internal or external dialogue, without a lot of world-building, scene-setting, or exposition.

These things led to an interesting experience if you were hoping to confront this old story from a completely new perspective. I wanted to embrace this book, but I struggled a bit.

The premise that the slaves spoke patois in front of the white “massas” but used the common language when alone seemed a natural outgrowth of their situation; they had to communicate important information with one another without the white people catching on to what was being said, and they had to hide their real personalities behind a façade of ignorance, foolishness, and passivity, so they learned code-switching from childhood. Everett completely enthralled me with this; but then he took it a little too far. I expected the character James to be a bit more than ordinary, given his interactions with Huck and others in the original, but did his life experience really allow him the latitude to become as extraordinary as Everett has written him?

He is painted as an educated man—not just a slave who has learned to read and to speak with a careful use of diction. Would the surreptitious reading sessions in Judge Thatcher’s study in the wee hours really lead to a thorough understanding of the works of Voltaire, Rousseau, and John Locke? Even southern college-educated men of that day were not necessarily cognizant of the intricacies of philosophical thought, so the requirement that we believe it of a man who has had to gain all his education on the sly in stolen moments is a little hard to meet.

This was, to my mind, a central flaw of this book, for the simple reason that we went from perceiving the disguise the original “Jim” presented to the world—the stereotypical shuffle-footed, awkward, ignorant, well-behaved and possibly well-intentioned slave—to yet another disguise for “James”—the cynical, perceptive, erudite man who is playing that character for half his world while laughing about it with the other half. I actually liked that for its dark irony; what I’m trying to say is that there was an opportunity here for us to get to know the real person, but except for some tantalizing and admittedly affecting glimpses here and there, we went from one façade to another. With as much internal dialogue as there was from James, there was nonetheless too little understanding of the man himself. While being able to recognize that he is quick-witted, thoughtful, and compassionate, I didn’t feel that I really understood how he acquired all those positive character traits, because he doesn’t let us in.

The other thing the book thoroughly exhibits is the two-faced nature of slave owners who wish to be regarded as benevolent protectors of their “childlike servants,” but turn on a dime, when challenged, to become brutalists who exult in wielding a belt or raping a child. And again, I found myself applauding the exposure of the stereotypes but wincing at the one-dimensional portrayals—not so much of the slave-owners, but of the slaves! Several other reviewers have noted that the women in this book seem to be present on the page merely to highlight their own ill treatment; they have no agency and almost no personality but are merely offered up as horrifying examples of the results of human ownership. Again, I have no quarrel with exposing the heinousness of the practice, but how much more affecting would the book have been had readers been able to better identify with these women as individuals with personality?

I don’t want to come across as hyper-critical of this book. I admired what he tried to do and was caught up in it while reading it. I am also a fan of his writing style and language, which can be beguilingly beautiful. It actually troubles me to go against the reviewers who gave it unreserved praise (not to mention the National Book Award!). But afterwards, while reflecting on what I had read, I also wished there had been more—more story, more depth of character, more nuance, more exploration. I am curious, now, to read others of his books to see what my reaction to him as a writer might be when not influenced by the rewriting-of-a-classic aspect of this one. I’m sure you’ll hear more about it from me eventually.

Discover more from The Book Adept

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.