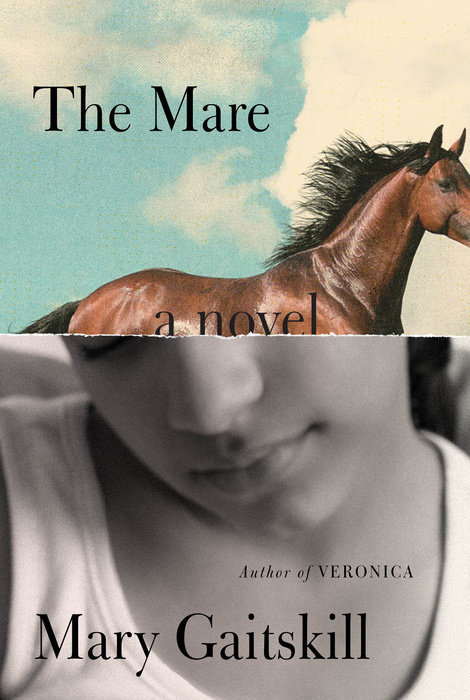

The Mare (the girl)

Having read Horse, by Geraldine Brooks, a few months back, when someone recommended the book The Mare, by Mary Gaitskill, I was primed to read it, especially because the teenage main character was named Velvet, immediately transporting me back to the joy of reading National Velvet in my childhood. And, similar to that book, this story was about a disadvantaged child whose encounter with horses changes things for her, although the child in this one is a much more extreme example. I didn’t grow up in a financial or social environment that would indicate the need for escape, but I was an introverted, solitary child who longed for the connection with horses in lieu of any relationship with people, so books like this spoke to me, and still do.

Velvet (short for Velveteen) Vargas is the daughter of a single mother, Sylvia, an immigrant from the Dominican Republic. They, along with Velvet’s little brother, Dante, live in Crown Heights (an inner city section of Brooklyn), and it is a limited, hand-to-mouth existence. Sylvia is hard and bad-tempered, shaped by the fearful responsi-bilities she has been forced to take on from a young age, and she is alternately loving, manipulative, and abusive with her children. The effect on Velvet’s sense of self, in particular, is both negative and confusing, and Velvet is a troubled, conflicted child.

Through Velvet’s school, they find out about the Fresh Air Fund; although the actual organization apparently sends children to six-week summer camps so they can have outdoor experiences and take leadership workshops, the program in this book pairs up inner-city children with more well-to-do host families from the country, with whom they spend a couple of weeks’ holiday. Both Dante and Velvet participate, although we never hear any more about Dante’s experience after he is put on a bus at Penn Station that first summer.

Velvet, age 11, is matched with Ginger and Paul, from rural upstate New York. Ginger is a painter, although she has been blocked for a long time; she is also a recovering alcoholic. Paul is a teacher, and met Ginger at an AA meeting. They have been together for some time without having children, and Ginger longs for some kind of connection; they initially sign up to host because Ginger wants to experience what it might be like to adopt an older child. (Paul has a daughter from a former marriage and is lukewarm, at best, about this.)

Ginger and Paul live near a horse stable, and it is the incentive of being able to ride horses that most appeals to Velvet about the experience. The book carries its characters through several years, as Velvet transitions from child to teenager while paying sporadic weekend and holiday visits to the couple’s home, and is told through the primary viewpoints of Velvet and Ginger, with a few scattered chapters giving added perspective from Paul and Sylvia.

The surface story is a coming-of-age saga, but the underlying context is the stark contrasts inherent in race and socioeconomic class. The switch between Velvet’s world and Ginger’s holds up the realities of inequality in our country by showcasing minority poverty and its relationship to white liberal guilt and its accompanying savior complex.

My reaction to the first part of the book was positive; it’s written in a rather quirky style that appealed to me because it was so internal. Conversations are had, but they don’t exist as present-tense dialogue; rather, each person is narrating from her sole point of view, and relating the conversations second-hand as she perceives them. It makes for an experience that is simultaneously cerebral and intimate.

The path of the story is choppy; sometimes we get to see the same scene and actions as experienced by Velvet and then again by Ginger, but at others we see things only from the one point of view and then the timeline is continued by the other, as when Velvet narrates her day at the barn and Ginger takes up the story when Velvet returns to the house and Ginger tries to get an account of the day’s events out of a recalcitrant and somewhat inarticulate teenager. Everything about the story is filtered through one or the other psyche (with the exception of the few short chapters related by Paul or Silvia), so there isn’t really a factual feel about it, since both viewpoints are opinion colored by personality and emotion.

Where the book started to break down for me was when Velvet (at home in Brooklyn) started paying attention to boys, and one boy, Dominic, in particular, and her attention is riveted on him to the exclusion of her own family, her host family, and the horses. Although it was probably a natural development in the life of a young girl from this neighborhood and, more widely, that of a pubescent girl from any neighborhood, it was a disappointing distraction from Velvet’s previous one-track focus on her almost mystical relationship with the horses and with one mare in particular.

The mare was a problem horse from whom everyone was warned off, as she was both unpredictable and occasionally vicious, but Velvet felt a kinship with the horse that developed, over the course of several years, into something so compelling that to draw the attention away from that to a helpless crush on an older boy who doesn’t really want her was disappointing. (Some of the best writing in the book is when Velvet is trying to articulate the feelings and internal dialogue between herself and the horses and how those translate into action.)

I also have to say that although I don’t mind stories that are more character- than plot-driven, I truly loathe ones that are open-ended, and when I got to the last page of this book I had a momentary flare of irritation that I had spent so much time persevering to finish reading it. In retrospect I don’t exactly regret it, but I really wish there had been a more definitive story arc with an end as engaging as its beginning.

Discover more from The Book Adept

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.