Person, place, thing

I wrapped up my wallow through the writings of familiar authors by reading two books that I really should have saved for six weeks or so but, once discovered, I couldn’t resist them. These were Jenny Colgan’s latest, a two-parter with the same characters and location, The Christmas Bookshop and Midnight at the Christmas Bookshop. Colgan has made a habit out of returning to the scene of a previous novel but setting the action at Christmas (Christmas at the Cupcake Café, Christmas on the Island, Christmas at Rosie Hopkins’ Sweetshop, etc.) but these sequels usually arrive after she has segued to another story or two and then returned. This two-fer is an almost-continuous tale all taking place within about a one-year period bracketed by Christmas seasons, so I was glad that I discovered them both at once and could read straight through from page one of #1 to the last page of #2.

My title for this review takes into account a particular skill of Colgan’s, which is to present us with compelling characters with a specific objective in a spectacular setting that becomes every bit as important to the story as the protagonists. In this case it’s the city of Edinburgh, specifically the Old Town shopping district, so far holding out (for the most part) against the store chains and gimmicky tourist fare to present an authentic experience of one-off original shops, from a hardware store to a chic dress shop to a witch’s herbarium. The focus for Colgan’s bevy of characters is, as frequently happens in her books, a bookshop, in this instance a failing one. Mr. McCredie’s ancestors started the rare book store on the rambling bottom floor of their home, and he has lived and worked there his whole life but, despite his affinity for and encyclopedic knowledge about every sort of book, he’s a terrible salesman, a worse marketer, and is on the verge of forfeiting everything. Enter Carmen Hogan.

Carmen has, in rapid succession, lost her boyfriend, her job, and her apartment, and has been living in a state of denial at her parents’ place, tediously and repetitively grousing about everything and eating way too much junk food. Carmen’s parents are rather desperate to get her out of their house and back on her feet, and enlist Carmen’s sister, Sofia, to help them.

Sofia and Carmen have always been polar opposites: Sofia is the elder type A overachiever, and is now a successful lawyer with a happy marriage, three children (and another on the way), and a beautiful home in Edinburgh, and Mr. McCredie is one of her clients at the law firm. Carmen decided to skip college, and has worked in retail in a large department store since high school until the store closed and made her redundant. Sofia somewhat reluctantly asks Carmen to come live with her family, telling Carmen there is a job for her revamping an Edinburgh rare bookshop; what she doesn’t tell Carmen is that the sole objective is to get the store to turn enough of a profit during the next three months so as to make it an appealing prospect to a buyer, and that as soon as a sale takes place, Carmen will again be out of a job (and presumably a place to live).

While initially reluctant to go live with her sister, Carmen sees that she needs a change, and she loves books, so off she goes to Edinburgh. She is horrified by the magnitude of the job she has taken on: The store is in an advanced state of disrepair and disorganization, and Mr. McCredie is absolutely no use unless someone comes in looking for that one eclectic title about which he happens to know something. But she takes a deep breath and pitches in, and starts to make some headway, particularly when she is able to get a famous writer of self-help books to do a signing at the store. This guy and a student/lecturer at the college are the two love interests in the story, and Carmen goes back and forth between the glamour of the first, with his casual attention and expensive dinners, and the quiet regard of the second, a young Quaker with an intensity she has never experienced.

Carmen and Sofia continue to be mostly at odds, but Carmen discovers an affinity for children, specifically her young nieces and nephew, that she didn’t expect, and bonds particularly with the second daughter, Phoebe, who shares many character similarities with her Auntie Carmen.

There are other fun, although somewhat over the top, characters such as Skylar, Sofia’s yogini nanny, and Jackson, the millionaire who is out to ruin the quaint shopping district by remaking all the stores into purveyors of cheap “tourist tat” sporting too much Scottish tartan, and there are a few improbable story elements that made me say “hmm.” But…

I was truly astounded to see a bunch of two- and three-star ratings of these books on Goodreads, where Colgan normally has solid fours and fives. I thoroughly enjoyed both of them; the magical descriptions of Edinburgh in winter at Christmas made me want to go there despite an almost pathological dislike of cold weather; the children were funny and endearing and memorable; the bookshop’s problems and mysteries were involving; and I liked Carmen as the protagonist and driver of the narrative. I was totally immersed in this two-part story for four days, and was sorry when it ended. I’m hoping, as she occasionally does, that Colgan will go back for a third installment set in this world with these people, because I’d love to know what happens in their next chapters. If you’re looking for something to read to put you in the holiday mood, look no further.

Riches

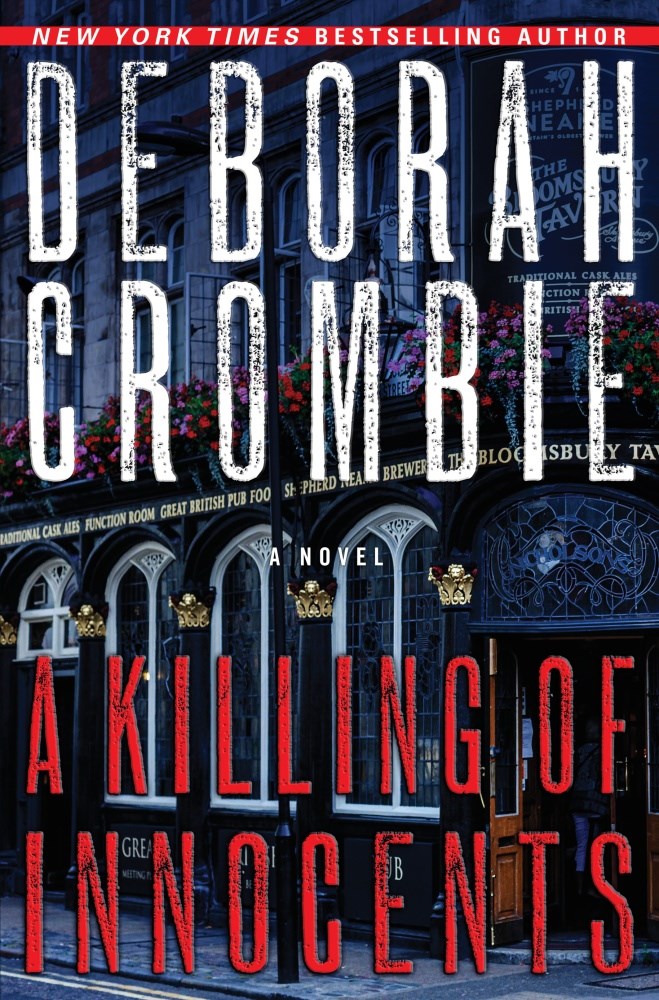

Sometimes forgetfulness or inattention is a gift. I was so busy for a while there trying out new authors and new titles garnered from various Facebook reading groups that I quit paying attention to the yield of some of my favorite mystery writers, with the result that I built up a backlog and got to enjoy three of them in succession: First I read the two Bosch/Ballard books by Connelly, then I followed up with the latest Cormoran Strike; when I finished that (which took some time, since it was 960 pages!), I remembered that I hadn’t checked on Deborah Crombie’s output in a while (I don’t check her too often because she’s an exceedingly slow writer, with as much as four years between books), and discovered she’d published a new one in February! This was a case of gulping down a dessert and then wishing retroactively that I’d made it last a little longer. I was still reading at the intense pace necessary to peruse a Cormoran Strike, but the latest Crombie book in the Kincaid/James series was only 368 pages, and I got through it in under 48 hours, reading at mealtimes and in the middle of the night when histamines from a recent prescription drug reaction kept me awake, and before I knew it, it was over.

I really enjoyed this one although, again, contrasting with the Strike tome with all its wealth of detail made me wish Crombie went a little more in depth into some of her subplots and red herrings to stretch out my experience! Still, we got a nice dose of the main protagonists, the secondaries, the friend circle, and a bunch of new and intriguing characters, and they sucked me into their messy, complex lives and made me want to figure out both the mystery and the relationships.

If you’re not familiar, Crombie’s series is about two detectives who are married to one another—Detective Superintendent Duncan Kincaid, and Detective Inspector Gemma James—although they didn’t start out that way at the beginning of the series (so this is a spoiler for those who haven’t read any of it yet, sorry!). They share a house and a life in London with children from separate previous relationships plus a recently added foster they acquired while together, and some dogs and cats. The books are populated with several significant co-workers and some old family friends from both sides who are ongoing, and then introduce one-off relationships related to the various cases in which they find themselves embroiled. I particularly like this literary pairing because Crombie alternates the lead detective in each book, so one will have Kincaid as the primary while the next will feature James, keeping things both fresh and non-sexist!

In this instance, Gemma has just taken a new position heading a task force on knife crime that places her primarily at a desk rather than in the field, so it’s Duncan who is called out to the scene when a young woman is murdered while walking through the well-populated Russell Square. But Gemma is rapidly involved as well when it turns out that Sasha Johnson, a young trainee doctor at a local hospital, has been stabbed. Is it part of the gang activity that Gemma and colleague Melody Talbot are investigating? It seems to have no connection; but another stabbing in a public park just days later seems to indicate a disturbing trend that will keep everyone looking for associations as they try to solve both cases.

This was well thought out and compelling, and I enjoyed the variety of characters and situations brought into the investigation as all involved look for clues to who might have wanted these people dead and why. Crombie is great at building suspense by switching POV, finding one fact, then changing again, letting each isolated realization begin to form a picture for the team. This was multi-layered with many threads, but they were and remained interesting right through an exciting climax and a satisfying wrap-up.

This series is now 19 books long, and it’s well worth your time if you haven’t tried it yet. I’m envious of those who haven’t, because once you’re caught up, it’s a long time to wait for the next! I keep threatening to start over at the beginning for a massive re-read, and I may well resort to that in the interim before #20.

Re-invested!

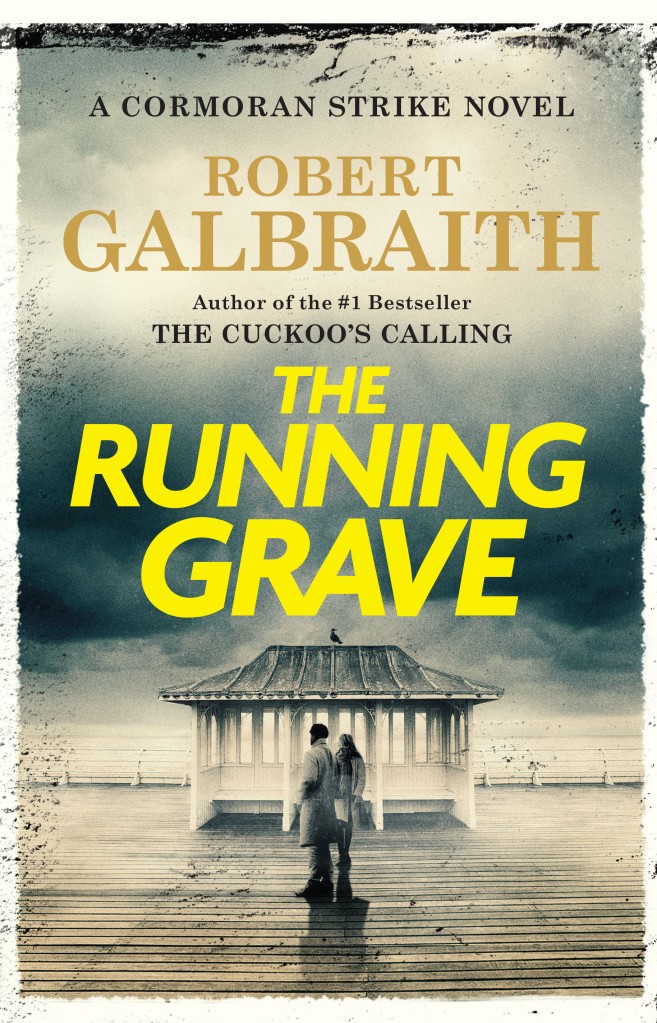

I just finished #7 in the Cormoran Strike/Robin Ellacott series by J. K. Rowling, and my complaints from the previous book are all forgotten in the sheer pleasure of reading this one. The Running Grave (named for a line from a Dylan Thomas poem that I find quite frankly incomprehensible) is likewise long, clocking in at 960 pages, although that still makes it 400+ pages shorter than #6; and the lack of those 400 pages may be one thing that improves this book to no end. But what caught me up in it was the subject matter (the culture and operation of a religious cult) and the resulting changes in the protagonists from their pursuit of this case.

Rowling was so clever in the staging and pacing of this story: Cormoran and Robin are hired by a frantic father to try to extricate his son, Will, from the Universal Humanitarian Church, on the surface a seemingly innocuous organization focused on a general sense of spirituality in service of creating a better world. But after hearing the father’s concerns about how they have prevented all contact between his son and anyone outside the bounds of the cult and then reading up on such rumors as unexplained deaths, compulsory sex, and severe punishments for the slightest infractions, Robin decides to infiltrate the cult. Strike is reluctant to let her be the one, but he is too well known himself to be able to create and maintain an alias, so Robin attends a public meeting of the church designed to recruit new members, and allows herself to be absorbed into their midst and transported to their “farm” in Norfolk for an undetermined length of time, her goal being to contact Will Edensor and see if he is amenable to leaving with her.

This is the genius of the book, creating the world of the cult members living at the farm for Robin to inhabit while keeping Cormoran outside following up on all their other cases, essentially unaware of what’s happening with Robin. They have a tenuous connection: She sneaks out of her dormitory every Thursday night and leaves him a note detailing her week’s experience, putting it in a hollow plastic rock situated in a blind spot near the fence to the outside world; but this weekly check-in is her only fall-back position to get out of what is turning into a seriously sticky situation. Being Robin, she is determined to stay until she achieves results, no matter how precarious things become; and being Cormoran, he is constantly worrying whether he needs to storm the front gate and pull her out of there for her own good. The back-and-forth detailing of the mundane running of the agency (and some rather amusing case work for Cormoran and the gang) with the surreal situation at the farm kept me turning pages every night long after I should have turned out my light and sought sleep.

(female saint in water, painter unknown, 1894)

There is also, of course, the ongoing situation between these two business partners who treat each other like best friends while dating other people because they’re afraid of ruining what they have professionally and are also both a bit cowardly about stating their feelings in the absence of certain knowledge about the reaction that revelation would receive. Robin is currently seeing Detective Inspector Ryan Murphy, while Cormoran uses typical bad judgment in his effort to find sex with no ties by getting involved with someone wholly inappropriate and potentially damaging to his (and the agency’s) reputation. But the longer Robin is sequestered in the cult, the more clear Cormoran becomes about what he really wants, and although nothing definitive happens in the relationship arena for most of the book, it’s not the frustrating experience we have endured for far too long, because we can feel something coming, and the cliff-hanger at the end of this one doesn’t disappoint.

What I am telling you is, if your loyalty has floundered in the face of weird plots on the mystery side and stalled emotions in the romantic sub-plot, I think based on this book that Rowling has hit the tipping point and things are going to get increasingly interesting in future tomes. Read The Running Grave and see if you agree!

Harry Bosch is 70

Speaking of a Golden Bachelor…it had to come sometime. Has there ever been another police officer who has joined and left the LAPD and joined up again so many times? and had a career that spanned three or four departments and several separate locations and even a different police department or two? Not to mention a brief foray as a private eye. Yep, Harry’s getting up there, and I don’t want to say that Connelly is phasing him out just yet, but the fact that he has, in each of the past five books, shared star billing with Renée Ballard says “transition” to me. Seventy isn’t so old these days, but after being exposed to cesium during a previous case, Harry’s mortality is apparently something to contemplate more immediately.

I’m not real happy about that; although I liked Renee well enough in her debut novel, when she appeared to be an outsider to rival Bosch—sleeping in a tent on the beach with her dog, and dividing her time between the police force and surfing—I have mainly read the Renée Ballard books because she always appears in conjunction with Harry, and when he’s no longer with us, I’m not sure she has the moxie to carry a series alone. While I would definitely call the Bosch books police procedurals, the focus has always been squarely on Harry, and his personality defines and permeates every story; but Renée doesn’t have the same spark, and I fear that once Bosch is no longer even an outlier, I won’t find enough pizzazz left to keep reading.

I read the latest Harry/Renée book, and then realized that I had missed the one just before that, so I went back and read that one. In The Dark Hours, Renée is still working “the late show” (the overnight shift) without a partner, but when she gets in too deep or needs some backup, she doesn’t call on a fellow officer, most of whom seem to be phoning it in since the twin discouragements of the “defund the police” movement and the Covid epidemic, but rather on the retired Harry Bosch, at home and at loose ends. This could ultimately get her in a lot of trouble with the department, but she’s a risk-taker and knows what she needs to get a solve on her cases; what she needs is Bosch. In this book the two have an almost instinctual camaraderie that is fun to watch.

There’s a big contrast between that book and the next one, Desert Star. In this latest Bosch/Ballard pair-up, Ballard has become almost unrecognizable as the junior-grade maverick following in her mentor’s footsteps. Towards the end of The Dark Hours, a disgraced Ballard had quit the force and was considering teaming with Bosch in a private detective firm, but at the beginning of this one she is back in the LAPD, and has been made head of her own department, examining cold/unsolved cases for the Robbery/Homicide division, and reopening ones that are viable for moving ahead, due to DNA evidence or other new information. This promotion seems to have turned her into a cautious, uptight, stuffy version of herself, and it takes practically the whole book for her to unwind back into the Ballard we’ve met before.

The inclusion of Harry is made legitimate this time, since Ballard is empowered to recruit him as a volunteer and he is more than willing to fill his time focusing on a multiple murder he was never able to solve. He’s supposed to be working on a case that is important to the city councilman sponsoring the new unit, but as usual Harry prioritizes what he believes to be more essential, and in so doing gets both himself and Ballard in hot water more than once. Most of it is believable, but when he takes off for Florida without telling either Ballard or his daughter that he’s going, it was one step too far into uncharacteristic behavior for me. I ultimately enjoyed most of this book, but it certainly didn’t make me warm up to Ballard or cease to dread the retirement of one of the best detectives any mystery novelist ever created.

Literature as solace

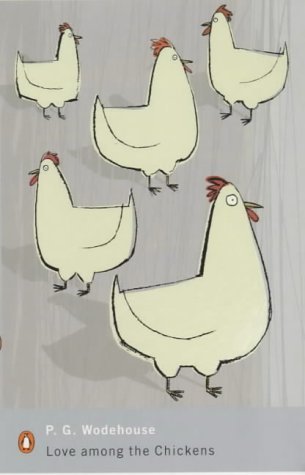

I’m not sure what to say about Good Night, Mr. Wodehouse, by Faith Sullivan. I was intrigued by the title, since I love what I have read by Wodehouse, notably the Bertie Wooster and Jeeves pairing. This book made me want to seek out his other books to see what I’ve been missing…but it didn’t particularly make me want to seek out others of this author’s. I did enjoy the book, but it’s what I would call a quiet read, almost too quiet for my taste.

It’s an old-fashioned story, told in a rather demure style (I wasn’t sure, initially, that this was a modern novel) about a woman who lives in a small town called Harvester, Minnesota, at the turn of the 20th century. The action begins around 1900 and finishes up when Nell Stillman is in her 80s, so the story encompasses many of the big changes of that century, including technological innovations (indoor plumbing, the telephone, airplanes) and two world wars, but all seen from the vewpoint of a 3rd-grade schoolteacher in a semi-rural, insular setting.

There isn’t much of a story arc; it’s more an accounting of one woman’s life as she moves through both historical and personal events. Hers has its share of tragedy and not a huge amount of joy; she is widowed young, loses her child’s sanity to the after-effects of war, and is plagued by the small-minded gossips and nay-sayers who surround her. But her growing love of all kinds of literature sustains her through many of her trials, particularly the writings of P. G. Wodehouse, with whom she has a personal relationship in her active imagination.

Life could toss your sanity about like a glass ball; books were a cushion. How on earth did non-readers cope when they had nowhere to turn? How lonely such a non-reading world must be.”

Nell Stillman, reader

The story has the feel, although not quite the literary quality, of the books of Kaye Gibbons; I haven’t read those for many years, but Gibbons’ book Charms for the Easy Life kept coming to mind for some reason while I was reading this—another small-town saga of generational and community ties featuring eccentric characters.

There were aspects that I found disappointing: A truly major character in the first half of the book (and my personal favorite) leaves the town in disgrace and the author simply drops her character except for a few sparse references towards the end. Similarly, when Nell is elderly she takes three young girls under her wing; they feature briefly but vividly, and then nothing more is heard about them. These weren’t major flaws, but they did cause my enjoyment of the book to be considerably less than if their arcs had been followed through.

I found Good Night, Mr. Wodehouse to be a pleasant read, but it left me with no desire to find out more about either the main character herself or the town of Harvester, which is apparently featured in others of Ms. Sullivan’s works. I did, however, identify closely with all her sentiments about the blessings being a reader brings to one’s life, so I do plan to find and peruse a copy of Love Among the Chickens!

Travel fiction

A “beach read” is defined as “a book, usually fiction, that one might enjoy during a vacation or a day at the beach because it is engaging, entertaining, and easy to read.” And without doubt a subgenre of the beach read is the vacation saga, the “let’s run away from our lives for a while and see what happens” theme, or what I like to call the sub-subgenre “travel fiction.”

The question you have to answer, with this subgenre, is how much bad writing you are willing to endure in order to have the escapist experience because, let’s face it, books that carry their British or American or Irish protagonists away from their various unfortunate events (break-up, lost job, eviction) and their inhospitable environments (damp, gloomy weather, or a small town where they can’t avoid their ex-whatever) are turned out without a lot of editing by a bunch of publishers on a quest to score the next Emily Henry or Elin Hilderbrand or Jenny Colgan novel.

Even with the bad writing contained by those novels not written by the top 10 authors in this field, it’s hard to stay immune to their charms. All of us have a fantasy of what we would do should we decide to abruptly leave our mundane lives behind and simply refuse to come home when our dream vacation is supposed to end.

I recently read two such novels, and have to say that I extended my tolerance for bad writing almost to the breaking point in order to go with the transporting experience of escaping to an unfamiliar and potentially beguiling part of Italy. The two books were One Italian Summer, and The Italian Escape, both by Catherine Mangan, and the constant balancing act was the repetitive language and clichéd sentiments expressed by and about the characters on the one hand, versus the heft of lyrical descriptions of the balmy atmosphere, delectable food, and romantic prospects.

I have never understood why writers make such heavy work of finding original language with which to tell their story—it’s sloppy. I, myself, when writing a book review, an essay, or a paper, simply read each sentence and paragraph aloud to discover if I have used the same word twice (or three times or half a dozen) within the given piece of writing, and then I go back and find another word or another way to express the sentiment, using a thesaurus to good purpose to give my writing the variation necessary to make it feel fresh. Furthermore, if the writer isn’t up to this task, the editor needs must.

I therefore laughed out loud, after reading the painfully repetitive prose of the first chapters of One Italian Summer, when I came to an exchange on pages 70-71. The main character, Lily, having escaped from a break-up in New York City to be maid of honor at a “destination” wedding, is breakfasting alone early on her first day at an Italian resort on the island of Ischia. At a nearby table is an American named Matt, who murmurs “Cranky person. Ten letters.” She asks if he is talking to her, and he replies that he’s two clues away from finishing the New York Times crossword puzzle. She supplies the word “Curmudgeon,” and he expresses doubt that that’s even a real word.

“It’s my job to know words,” she replied matter-of-factly.

“You’re a writer?”

“No, but I write for a living.”

“Okay, is that supposed to be cryptic? How can you write for a living but not be a writer?”

“I’m a copywriter. I write for a living, but it’s just blurb for adverts and products, so I honestly can’t call myself a writer, not in the true sense of the word.”

Then she goes on to provide his final word, which is “capricious.”

“You’re like some sort of crossword Olympic champion!”

“I just need to know a lot of words in my line of work because you can’t keep saying the same thing over and over.”

Lily, p. 71

I laughed because this came after pages of heavy-handed, somewhat pedantic scene-setting narrative and excessive use of the words “so,” “like,” and “really,” not to mention describing someone as a “hot sweaty mess,” then a “shiny mess,” then a “pathetic mess,” in the space of six consecutive paragraphs.

If you can get past such pet peeves, the basic story lines of both of these books are sufficiently escapist to entertain anyone seeking a light read about a fantasy trip; in addition, the location of said trips, slightly off the beaten path of the usual retreats (Ischia rather than Capri; and Liguria, rather than Milan), make for some entertaining speculation about exploring them for yourself someday.

Both books include a little romance for their protagonists, but that is refreshingly not the main theme; rather, it’s the discovery of unexpected depths that lead to life changes. The first book details a week-long itinerary surrounding a lesbian wedding celebration, all of it fraught with way too many drunken evenings described in excruciating detail, while the second is the transformation of a Dublin girl who’s been dating her boss at a business with which she has little affinity who decides, after she’s dumped, that a big change is in order, and refuses to go home when her week in paradise is up. There’s a bit too much interference of a deus ex machina in the form of a wealthy, powerful, and indulgent older woman who takes a liking to protagonist Niamh and smooths her way to a ridiculous degree for a chance-met stranger, but hey, who doesn’t dream of a fairy godmother and wish to immerse themselves in this kind of fantasy?

Bottom line: Not too demanding, pleasantly diverting and, if you’re a foodie, way too provocative!

Immersive

I just finished a re-read (for the third—or fourth?—go-round) of Rosamund Pilcher’s book, Coming Home, which has to be one of my favorite books, as much as I try not to name favorites (because it always provokes a way-too-long list in my head and ends up getting re-ordered during hours of insomnia). Pilcher is sometimes under-rated because of a handful of (short) books she wrote that are obviously formula-driven romance novels, and people expect all her writing to be the same, when, in fact, it’s almost as if (except for the Cornwall setting, which remains pretty constant) there are two writers, with the second waiting to emerge when all the formula stuff was out of her system.

Her most famous books are The Shell Seekers and Winter Solstice, and I love (and re-read) those as well, but for me, Coming Home is the definitive book of her career. It’s a coming-of-age story set within the framework of World War II, beginning in the pre-war years and ending after the war is over. It follows the life of Judith Dunbar, whose father works for a company in Ceylon; Judith spent her first 10 years there, but when her younger sister, Jess, came along, her mother brought the two girls back to England, to Cornwall, leaving her father to a bachelor existence. (This was a common living situation in a time when it was considered dangerous to try to raise Caucasian children in that hot climate.) Now Jess is four years old and Judith is 14; in 1935, their father receives a promotion to a position at the company’s offices in Singapore and wants his wife with him, so Mrs. Dunbar and Jess are traveling back out to the East, while Judith will stay in Cornwall, attending a boarding school in Penzance and holidaying with either her father’s or her mother’s sister, both of whom live fairly close by.

Judith’s existence is transformed by her friendship with a week-to-week boarder at the school, Loveday Carey-Lewis, who returns home each weekend and invites Judith to accompany her. These British aristocrats have an extensive estate called Nancherrow, out at Land’s End, with luxuries about which Judith has never dreamed—a butler, a cook, a nanny, stables, their own cove and beach—and soon Judith is welcomed as one of the extended family by Loveday’s glamorous mother, Diana. But the war imposes hardships on everyone, lower class to royalty, and Judith has her share of life changes that determine her responses to both love and tragedy as the years pass.

It doesn’t sound like such an exciting story, detailed here, but there is something so poignant and so immersive about the stages of Judith’s somewhat lonely teenage and young adult years, especially set against the magical backdrop of Cornwall (and her adoptive family) and dealing with the sobering consequences of living in a country at war. The joys, the sorrows, the suspense about which way the story will go next always hold me enthralled from beginning to end.

I also confess that the artistic aspect Cornwall represents, with its Newlyn School of painters (that are also detailed in Pilcher’s The Shell Seekers), is an additional draw for me. Pilcher’s books, along with Daphne du Maurier’s, are the reason I spent 10 days in Cornwall in April of 2002; my cousin Kirsten and I rented Whitstone Cottage from the National Trust, formerly inhabited by the blacksmith for the Penrose estate between Helston and Porthleven. After reading about it for all those years, it was like coming home for me!

If you’re in the mood for an intimately personal tale with an historical backdrop and multiple settings that portray various ways of life during that time, be sure to check out this book. If you’d like to read an amusing anecdote about our stay in Cornwall, go here.