Coming of age w/dogs

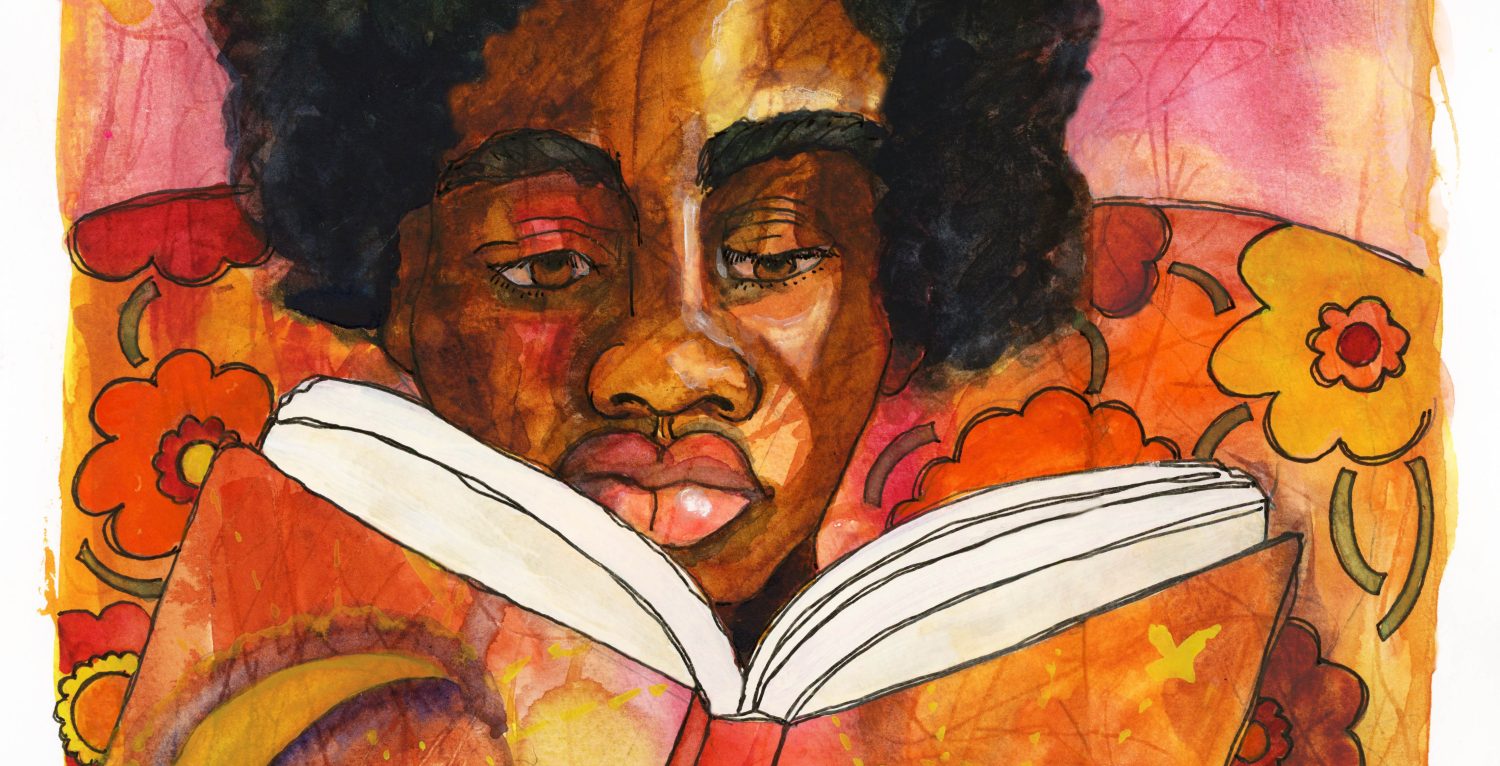

I somehow never picked up The Story of Edgar Sawtelle, by David Wroblewski, back in 2008 when it was published and getting all the buzz. I had started my first job in my new career as a youth services librarian, and was far too exhausted ordering books for the library and trying to get current on children’s literature to read much of anything for my own pleasure. I was buying some remaindered books from bookoutlet.com recently and saw that it was available, so I included a copy in my order and started reading without knowing anything about it.

It reminded me, with its gorgeous prose, descriptive scene-setting, and intriguing characters, of a few other books I have lately read—This Tender Land, by William Kent Krueger; The Extraordinary Life of Sam Hell, by Robert Dugoni; and Where the Crawdads Sing, by Delia Owens. Like those books, it has a young protagonist with a challenging facet to his character, and is both a coming-of-age saga and a snapshot of the times and locale in which its events take place.

In This Tender Land, the boys are orphans being raised in a reservation institution during the depths of the Depression; in Sam Hell, the protagonist is born with red eyes, an odd genetic marker that is a target for bullies; in Crawdads, Kya grows up in isolation in the North Carolina marshes after being deserted by her family, and is regarded with suspicion by the rural community surrounding her. Edgar Sawtelle is more fortunate than these others, in that he has two loving parents and a meaningful life working on his family’s farm in northern Wisconsin, breeding and training dogs for sale. But Edgar has his challenge, too: He was born mute. He hears, but is unable to speak, scream, or make any kind of verbal noise. He is fortunate to meet a woman early in life who teaches him and his parents to sign, and he and his mother go on to make up their own peculiar gestures for all the dog-related trainings, which he does silently with his hands while she verbalizes.

When Edgar is a teenager, his uncle Claude comes back into their lives (he has been in prison), and as soon as he is on the scene, things begin to change. Edgar’s father and his uncle quarrel almost constantly, his father’s native caution coming up against his uncle’s rash impulsiveness. It begins to seem like they are all doomed to live in a constant state of turmoil. Then Edgar’s father dies unexpectedly, leaving he and his mother to carry on the ambitious and taxing breeding and training program with the family’s dogs, and Claude begins to insert himself into the business as his mother, bereft and grieving, reaches out for help. When Edgar has an astounding realization about Claude’s character and actions, he lashes out with tragic consequences and flees into the woods with three of the dogs from “his” litter. But he can’t stay away forever, and is ultimately forced to face the consequences of his flight.

The book has been called a riveting family saga and a compulsively readable modern classic, and I couldn’t disagree with either of those descriptions. Edgar is an immediately sympathetic character, beset by frustration and grief and unable to make himself understood. The story is so moving, in both its triumphs and tragedies. There are those who quibble that the details of the dog breeding and training involve way too much description and attention, just as some readers disliked the lengthy descriptions of nature in Crawdads and asserted in each case that these were flaws of a first-time writer; but I actually enjoyed learning about this trade, and also specifically how it was undertaken by a boy who was mute and couldn’t call out his commands. Others decry the hint of magical realism and/or the anthropomorphism involved in having a few chapters told from a dog’s point of view. But for me, the characters of both the humans and the dogs come to life on the page and are so distinct and compelling that it’s hard to leave them behind when the book is over.

I honestly don’t know what to say, however, about the resolution of the book. I kept expecting, despite all the portents, for it to be a heart-warming boy-and-his-dog story, and up through about 75 percent of it I hung onto that; but the last 25 percent devastated me. After it was over, I went back to Goodreads and discovered that the author had patterned the book on Shakespeare’s Hamlet. It might have been good knowing that, going in! I can’t say that I wouldn’t have read it anyway; but perhaps I wouldn’t have invested so heavily in my belief that there would be a redemptive, if not precisely happy, ending.

I have probably said too much for either proper readers’ advisory or a book review; but it’s hard to get over the emotion that was provoked by this book. It’s beautiful, evocative, and tragic. I would still say to read it, but hold a tiny part of yourself in reserve from wholly committing to the characters.

More Barclay

It turns out that my last read by this author, No Time for Goodbye, has a sequel, called No Safe House. So I decided to read that too, but while I was waiting on a copy from the library, I picked up his book Never Look Away. I think this one is my favorite so far, in terms of the drawn-out suspense.

It actually answered questions that came up when I read his more recently published Promise Falls series. It’s the back story of one of the protagonists from that series—David Harwood, the newspaper reporter. There are comments made in that series about the tragic events involving his wife that took place the last time he lived in Promise Falls, and this book tells that story.

David and Jan Harwood have been married about six years, and have a darling four-year-old boy, Ethan. But lately Jan seems to be struggling with depression. She isn’t able to articulate what’s wrong, so David encourages her to see the family doctor for a talk, and hopes for the best. They make plans for a little getaway one Saturday, taking their son Ethan to a new amusement park that has just opened. But shortly after they arrive, Jan takes her eyes off Ethan’s stroller for just a couple of minutes, and when she turns back, he’s gone. The parents split up to search the park and finally, when they have almost given up, David spots Ethan’s stroller, with a suspicious-looking man running away from it. He’s relieved to find Ethan unharmed—the kid apparently slept through the entire abduction!—and calls Jan’s cell to let her know everything is okay. David waits with Ethan just inside the park for Jan to meet up with them, but after standing there for a really long time, David starts to wonder—has he found Ethan only to lose his wife?

In the days that follow, David’s work life impinges upon his personal situation in such a way that the police start to look at him with suspicion in the matter of Jan’s disappearance and continuing absence. It’s up to David to figure out how he could have gotten his signals so crossed up and what, exactly, has happened to Jan…and why.

No Safe House takes us back to Cynthia (Bigge) Archer, whose family disappeared without a trace one night when she was a teenager. This book takes place six years after the end of No Time for Goodbye; Cynthia’s daughter Grace is now 14 years old, and is responding with typical teenage contrariness to Cynthia’s admittedly somewhat paranoid attempts to keep a tight hold on her schedule. After a particularly fraught interchange, Cynthia moves out of the house and into a sublet apartment to take a break from family life, leaving husband Terry, who’s a little less tightly wound, in charge of Grace. Grace takes advantage by telling her dad she’s going to the movies with a girlfriend and will get a ride home from the friend’s mom afterwards, but instead going out with Stuart, a former student of her father’s who is a couple of years older and exemplifies trouble on two feet. Later that night, there’s a panicky call from Grace to her dad: “I think I might have…done something.” And this sets off events that bring the family back in contact with the lawless Vince, who helped them out during their drama six years ago and suffered for it, and Vince’s stepdaughter Jane, who proves to be a tower of strength for Grace. Things escalate, as is typical of Barclay stories, and stay pretty exciting and perilous throughout. I enjoyed this follow-up even more than I did the first book.

I’m going to take a break now from mysteries to embrace some other genres, but I’m sure I’ll be back with Mr. Barclay someday soon.

Promise Falls

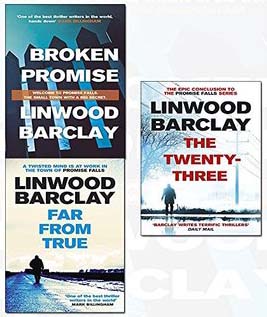

On the recommendation of my friend Patrice, who also enjoys mysteries, I checked out a few books by Linwood Barclay, whose writing I had yet to explore. It just so happened that a fairly recent trilogy by him was available through the library (e-books), so I first read Broken Promise, Far From True, and The Twenty-Three.

The structure of this trilogy seemed to me like an anomaly among mystery writers: Although many write series featuring the same detectives, most of the books in those series are self-contained; that is, a mystery is opened at the beginning of each book and solved by the end of that same volume. But this trilogy carried several complex situations over from book to book, so that small parts were solved in books one and two, but it took until book three to reach final resolution on all sides.

Additionally, instead of just one detective protagonist (or a team), these books feature three protagonists, each with a different profession and a separate agenda, although all of them are ultimately interested in solving the complex situation taking place in Promise Falls, an upstate New York town seemingly plagued by bad luck.

We are introduced to the town in Broken Promise by David Harwood, a “native son” who decides to move back from Boston and a decent (though stressful) career as a reporter, after the passing of his wife. He applies for and gets a job at the local newspaper, only to have the paper fold within a week of his returning home, and he and his son Ethan are stuck living with his parents until he can figure out some other way to support them. Then his cousin Marla, who suffered a recent devastating loss when her child was stillborn, turns up with a baby that is not her own. She claims the child was left with her by an “angel” who exhorted her to care for it; but when the child’s mother turns up murdered, all eyes are on the somewhat unstable Marla as the culprit. David puts aside his own concerns to focus on finding out the truth, but other strange events in town muddy the waters even further.

The second book, Far From True, features Cal Weaver, a private investigator who, subsequent to a major tragic event that takes several peoples’ lives, is hired by one of the deceased victims’ daughters to look into a break-in at his house. Cal discovers far more about a number of supposedly upstanding town citizens than he ever wanted to know; but how are their activities related to the break-in, and are they also connected somehow to the murders the local police are still trying to solve?

The third book’s narrative, The Twenty-Three, is primarily driven by Detective Barry Duckworth, the lead officer on almost every criminal case in Promise Falls. Right now he is feeling out of his depth, torn in five different directions, between the murders he has yet to solve, the new and ominous events that are piling up around the significant number 23, and the latest disaster that is sending a good portion of the town’s citizenry to the emergency room—and some to the morgue.

Although each of the books begins with a particular narrator and may feature more details about that person and his efforts, all three of the protagonists appear in each of the other books as well, and it’s a bouncing timeline that jumps from one crime scene to another, from one character to another (and not just the protagonists), from one interview to another, as the three pursue their separate agendas but also come into contact with one another—sometimes for an amicable exchange of information, other times as opponents or even suspects.

I enjoyed these books in a different way than with regular mysteries, since the cases took three books to solve; the pace is more leisurely and allows you to get to know the characters better (and also for the author to add characters without too much confusion as to who they are). At first I did have to pay close attention to the different story lines between David and Cal, because they are about the same age and share some of the same concerns and characteristics (intelligent, curious, fit, interested in some of the women with whom they interact); Barry Duckworth was much easier to keep separate, since he was the only policeman involved (initially), as well as being a decade (or two) older than the others, married, and described in different terms (a big gut owed to an irresistible sweet tooth, a sweaty suit and tie rather than casual dress, etc.). I liked having all the different perspectives from which to draw conclusions, and I also appreciated Barclay’s introduction of other colorful characters from the community, particularly the former (and hoping to be future) mayor, a genial sociopath who mucks up the works for all of the crime-solvers in his attempts to be both relevant and constantly in the public eye.

In the end, it was a lot to wrap up, even for a trilogy! Serial murders, sex scandals, opportunistic former mayors, a series of what amounted to terrorist attacks on the people of Promise Falls…and basically only two detectives and a couple of well-meaning amateurs working full-time on all of it. In the hands of a less skillful author this would have become a confusing mashup, but I feel like Barclay handles the multiple trains of thought well and keeps everything focused in the general direction he wants things to go. I saw one of the guilty parties coming, but only because our attention was so firmly directed towards someone else; but I was blindsided by the other one. A good conclusion, although Duckworth’s final situation left something to be desired—by him! Still, he knows he has cake in his future…

After completing the trilogy I decided to read a few more of Barclay’s books, which are for the most part stand-alone. One, Too Close to Home, harks back to a specific event in the history of a minor character from the later trilogy; Derek Cutter (father of cousin Marla’s baby in the trilogy) was just 17 when the family next door were all brutally murdered while he hid in their basement. Barry Duckworth has his eye on Derek as his prime suspect, and Derek’s father, Jim, has to do some quick work to figure out who else besides his son could have done the deed and, almost as important, why? Soon Jim has a potential culprit in his sights, but Jim’s wife, Ellen, thinks Jim is taking this opportunity to exact revenge on a former rival. Getting to the truth proves more complex than anyone expects.

The other, No Time for Goodbye, has a fascinating premise: One morning when she is 14 years old, Cynthia Bigge wakes up to discover that her entire family is missing from the house—her mother, father, and brother Trevor. The cars are both gone, and she initially assumes that they have left for work, school, or errands before she came downstairs. When they don’t return, however, the suspicion by the authorities is that they have left—and left her behind. There’s no note; no clothes or possessions are missing; there are no circumstances that overtly indicate a violent end; it’s completely baffling. Twenty-five years later, Cynthia and her husband and daughter are dealing with the trauma afresh, after Cynthia goes on one of those television documentary shows that tries to solve cold cases. Weird things start happening: A car lurks in the neighborhood and seems to follow Cynthia when she walks Grace to school; an anonymous phone call hints that the mystery should be abandoned; a strange artifact from the past appears inside the house. Cynthia’s husband, Terry, is trying his best to be supportive, but can’t help wondering if it’s all a figment of Cynthia’s anxious imagination—or worse, that she’s the source of all of it. Cynthia, determined to solve the mystery, hires a private investigator, and his actions soon send things out of control.

I really enjoyed both of these books. The writing is engaging and entertaining, the plotting is smart and convoluted without being confusing, and the outcomes are nearly always unexpected. I would probably label his books thrillers rather than straight mystery, although there is an element of detecting going on throughout. But the pacing and the level of suspense (and the ultimate revelations) definitely qualify as thriller material. I’m happy I’ve been introduced to Linwood Barclay and will look forward to reading more.

Crossover nuances

I was trying to decide what genre would next receive attention for possible summer reading recommendations, as August winds down. Some people who are turned off by traditional fantasy (quests, medieval societies, talking animals, etc.) are hooked by what some designate as urban fantasy—a story that takes place in a contemporary setting with “normal” people, but eventually fantastical creatures or events invade that space and change it or them. I started pondering, then, what crossovers there are with urban fantasy—so often, paranormal creatures are the fantasy part of urban fantasy, so I looked to my paranormal list to see what fit and what didn’t within that broader category. It also crossed my mind that works of magical realism could, in some cases, twin as urban fantasy. So this will be a mashup of all of those, which, while technically being separate genres, share the characteristic of something “wyrd” intruding on everyday life. (It is obviously not comprehensive, since that would take a post five times as long. But hopefully it is a representative offering.)

The first urban fantasist who comes to mind when thinking about that genre (at least for me) is Charles de Lint, a writer who sets all of his stories in the fictional Canadian city of Newford. People refer to his work not only as urban fantasy but as magical realism and mythic fiction but, whatever you call it, it’s compelling. He has written at least two dozen books that are consciously numbered Newford #1-21 etc., but many of his nondesignated works also take place in and around that city and its anomalies, as well as several collections of short stories featuring characters from various novel-length works.

I have enjoyed reading most of his books, but my two favorites are Memory and Dream, and Trader. Memory and Dream takes place mostly in flashback: It begins with the story of an artist, Isabelle Copley, who has retreated from the city to an island where she isolates herself and paints only abstract works; but in her youth, she was a vital part of the art scene in and around Newford, and studied with a master painter who abused her but also taught her a method of painting that could (at least theoretically) bring the subjects of her portraits to life. Trader is about a musician and craftsman (he makes musical instruments, mainly guitars) who is going through a bad patch in which he has no joy in life and no appreciation of his situation. Across town, there is another man who is going through an actual (rather than psychological) life crisis generated by his own bad behavior—he’s a gambler and a cheat, and has just been evicted from his home with only the clothes on his back. He has come into possession of an Inuit artifact and, as he goes to sleep that night, he clutches it in his hand and wishes hard for his life to get better, just as the other man is wishing the same. In the morning, everything has changed for both of them.

While de Lint’s books are filled with both events and characters who are out of place in their everyday environment, his are based on myth and legend (mostly from the Original Peoples), with archetypes such as Coyote and Crow (as well as more whimsical made-up characters) making appearances. But the next writer who springs to mind—Seanan McGuire—has much more crossover with the paranormal genre than with magical realism, because her unorthodox characters are mostly scary supernatural creatures—were-people, sentient snakes, monsters that cause those bumps in the night. The protagonist and her family call them cryptids. The early books take place in New York City, where Verity Price (a cryptozoologist) is working in a bar while trying to become a competitive ballroom dancer. But she keeps getting drawn into conflicts between the native cryptids, both advocating for and fighting on their behalf for their right to life against the monster-hunting society called the Covenant of St. George, whose members are dedicated to wiping out the monsters one and all, regardless if they are talking mice or dragons in the subway system.

In addition to these InCryptid stories, McGuire writes another urban fantasy-ish series called Rosemary and Rue, around the protagonist October Daye, a half-human, half-faerie changeling who keeps getting burned by both sides of her heritage. It is set in San Francisco, and is about the remains of the fae (faeries) who exist in the cracks of that city and keep intruding on its existence, sometimes in nefarious ways. Although McGuire has a lot of fans for this series, I found it wordy and tedious compared to the witty, light-hearted tone and fast pacing of the Incryptid books.

Finally, McGuire has a new series about which I have raved in reviews on this blog: the Wayward Children books. They are compact little gems of literary writing based around the fascinating premise that some of the children who disappear every year into the back of the wardrobe or under the faeries’ mound on the heath or down the rabbit hole have been kicked out of their alternate worlds back to this real one, and their sole desire in life is to return to whatever world they discovered when they walked through that mirror. Eleanor West runs a Home for Wayward Children that takes in these unhappy souls; their parents believe that West is attempting to re-acclimate them to their mundane life in this world, but Eleanor’s secret goal is to aid them in finding their way back to the magical lands they long for.

A couple other well-known urban fantasy writers are Jim Butcher, who writes the engaging Dresden Files, about wizard Harry Dresden, who consults with the Chicago P.D. whenever a crime seems a little “out of this world” to be solved by a mundane police force; and Charlaine Harris, who has written full-on paranormal (vampires as a part of everyday life in the Sookie Stackhouse books) and also has been more restrained (as in the wonderful Harper Connelly series, about a woman who was struck by lightning and can, as a result, stand on someone’s grave and tell you how they died). Harris has recently extended her imaginative worlds into both alternate history and dystopian fiction with her Gunnie Rose series, which is also urban fantasy with the inclusion of wizardry by Russian and British practitioners.

There is some debate about whether Melissa Albert‘s books The Hazel Wood and The Night Country should be included in the urban fantasy category, since they are predominantly new fairy tales. But the fact that the protagonist and her mother live in the real world while her grandmother, who wrote a cult classic book of dark fairy tales, has thus created the Hinterland, a parallel land into which the protagonist ultimately travels, makes this duology a candidate for both.

It is difficult—and sometimes arbitrary—to differentiate between urban fantasy and paranormal as two different categories, and after thinking it through, I have decided for myself that the paranormal books only qualify as urban fantasy if the urban setting and mindset predominate. In other words, the scene is first and primarily set in the real world, and the fantasy intrudes upon it to the surprise of the characters living in that setting.

One young adult duology that I adore that qualifies in both categories is Lish McBride‘s Hold Me Closer, Necromancer, and its sequel, Necromancing the Stone. While both books are filled with all sorts of paranormal critters, the first book starts out in a commonplace setting and with an all-too-characteristic protagonist. Sam lives in Seattle, still at home with his single mother despite having graduated high school. He’s not exactly a loser, but he lacks focus and ambition; rather than going to college, he has chosen to continue working in the fast food joint where he and his friends have a light-hearted routine of playing “potato hockey” in the back parking lot during slow periods. But when a potato flies out of control and smashes the headlight on a brand-new Mercedes, Sam comes to the attention of Douglas, a scary dude who turns out to be the neighborhood necromancer and reveals to Sam that he, too, has this “gift.” Douglas is threatened by the presence of what he sees as a rival for his territory, and gives Sam an ultimatum; but Sam, baffled by this amazing discovery, feels helpless to know what to do. Fortunately, his mother, his uncle, and even some of his friends have abilities that can help him out of his dilemma.

Another young adult author who specializes in the urban fantasy/paranormal mashup is Maggie Stiefvater. Some, like her Wolves of Mercy Falls books, fall more heavily on the supernatural side, with setting being instrumental (the necessity of a cold climate) but not primary, while others, such as her Dreamer books, feel a lot more like urban fantasy. The Raven Cycle, four books set in the small town of Henrietta, Virginia, straddle the line between urban fantasy and legend. All are intriguing and beautifully written.

Then we come to the crossover with magical realism. Urban fantasy and magical realism have the connection that there are uncanny things happening within a mundane setting; but in magical realism, the setting is often not as important, and this is seen by some as the dividing line. Who could argue, though, that it wasn’t crucial for the book Chocolat, by Joanne Harris, to be set in the straight-laced French village of Lansquenet, with its narrow-minded mayor and contentious residents? Or that the events in Practical Magic, by Alice Hoffman, would have had the same impact had they not taken place in the Massachusetts town where the Owens women had been renowned for more than 200 years as witches? Or that the events of Once Upon A River, by Diane Setterfield, would have differed significantly had they not been centered on an ancient inn on the banks of the river Thames? Looking through my list on Goodreads of the 50+ books of magical realism I have read, these are three that stand out for their significant settings, while the others could most of them have happened anywhere, as long as it was within this ordinary world and featured extraordinary events or characters. But you can see that there are commonalities that can be significant.

The bottom line for me is that all of these permutations contain the wonderful premise that there are things taking place around us in our everyday lives that, could we only look up at the right moment and see them happen, would change everything in a heartbeat. I love this premise and, therefore, the books that promote it, be they classified as magical realism, paranormal fiction, or urban fantasy. I hope you will find a book or two from this blog post that appeal to you in the same way they have to me.

Illustration

In the category of “Better late than never…”

I had a lesson this week in my year-long portrait-painting class that took as its inspiration Picasso’s harlequins. It was a complicated, lengthy, and convoluted lesson and I almost didn’t do it…and then I got an idea. I decided, instead of painting the boy and girl harlequins like the teacher did, that I would illustrate Robin Hobb’s fabulous Farseer books by making a painting of one of the main characters, the Fool, an albino court jester who (in the early books) sits at the feet of King Shrewd, dressed in black and white motley and playing with a rat-head marotte. So I did, and here it is!

The teacher who taught this lesson is a big proponent of collage, and I found some fun and symbolic stuff for this one. In addition to using tissue paper to good purpose for the ermine of the King’s cloak, I found a dragon, which figures significantly in later books; a Queen of Hearts card, which I interpreted as Queen Kettricken, my favorite female character (well, she was until Bee arrived); and a tiny jester, who is gesturing up towards my Fool from the corner.

Perhaps this will intrigue more readers to look into Robin Hobb’s three trilogies about the Farseers!

Robin Hobb wrote the Farseer Trilogy, the Tawny Man trilogy, and the Fitz and the Fool trilogy. There are also other books set in the same universe, about the Liveships and their Traders, the Rain Wilds, and the Elderlings.

Light relief

Sometimes, when you have been reading serious stuff—whether it’s stark realism, a western set in a dystopian world, or an intense (and long) immersive fantasy, you just need to indulge in some junk food. Lighter fare. In other words, chick lit. And if it has paranormal overtones, so much the better!

I have noticed a trend, also, that requires I seek out this kind of fiction occasionally: When I am painting intensely, I want light reading, and when I am reading something heavy, I don’t paint anything too challenging. So I guess what I am discovering is that balance is important, even in cross-disciplines? (Now, if could only find something to read that would make me want to do housework compulsively for about a week…)

I started on this chick-fest with Girl’s Guide to Witchcraft, by Mindy Klasky. I don’t recall precisely how I came across the book, but once I had read the description, I was a goner: The main character, Jane Madison, is a librarian (ahem), and when her library experiences funding difficulties, her boss breaks the news that she is about to suffer a 25 percent cut in pay; BUT, to compensate, she will be allowed to move into an empty cottage on the library grounds (it’s an historical library in Washington D.C., surrounded by extensive gardens) and live there rent free. Jane can’t really afford to turn down this offer; plus, the cottage is within walking distance of work, so she will save gas as well as rent. She and her best friend Melissa (yes, I know, but I am determined to be JANE) spend a weekend cleaning out the place, except for the cellar. A while later, Jane decides to see what’s down there, only to discover an extensive book collection (as well as other artifacts) placed there under ward by a famous witch. Guess what happens next?

When I was in my early 30s I worked in Hollywood as a movie title designer. The office was about a 30- to 45-minute drive from my house in typical Los Angeles traffic, with the result that I spent all daylight hours either driving or at work. The typography studio was in a primarily industrial neighborhood with no restaurants close by, so I mostly brought my lunch. But if I ate it at my desk, I would inevitably get 10 minutes max before someone needed me for something, and there went my lunch hour, so I went looking for somewhere else to enjoy my sandwich and chips. There were no parks close by, but there was a cemetery, backed up against the Paramount lot, and it was beautiful, with a lake, lots of mausoleums and sculptures, and benches strategically situated in the shade of large spreading trees. After eating, sometimes I would go gravestone browsing to see what famous or infamous people I could turn up (not literally). Along one wall of the cemetery there was what appeared to be a stone cottage, built right into the wall. It was most likely a garden shed where tools were kept, but it looked like someplace a reclusive witch (or an indigent typesetter?) would live, however macabre that sounds. So when I read the part of Klasky’s first book about the cottage in the library gardens, I was immediately hooked.

Needless to say, I had to finish out the trilogy, which details Jane’s journey as she comes into her witchy powers, works an accidental love spell that apparently connects with everyone from the library janitor to her own warder, and alienates the head witch of the Washington Coven. There is also a lot of “girl” time with friend Melissa, who is the local baker of delectable pastries and cupcakes and is always up for a Friday night of muddling mint leaves from Jane’s garden to make a pitcher of mojitos over which they can discuss their love lives.

Then I discovered that there were two more books, in which Jane starts her own (highly irregular) school for witches and has to fend off magical rivals and the beasts they send to deter her, so of course I had to proceed. There was also a 3.5 crossover novella that introduced me to a new character, Sarah, clerk of court for the District of Columbia Night Court (the secret after-hours Capitol court for paranormals). Sarah is (of course) a sphinx, charged with the protection of vampires (who knew they needed it?); she contacts Jane for assistance with a library of vampire lore in disarray and I (of course) was lured down this side pathway to read Sarah’s own trilogy, which involves her coming into her own as a sphinx and trying to decide whether to pursue romance with the very nice and compulsively tidy Chris, a reporter for a local newspaper (or is he?), or the darkly dangerous but infinitely appealing James, her vampire boss, head of security for the Night Court.

Finally, when I thought I had come to the end, I discovered one last volume, called The Library, the Witch, and the Warder, which circles back around to tell the Jane Madison story from the viewpoint of her warder, David Montrose. But I swear, THIS is the last Mindy Klasky book that will capture me with its lure of magic, romance, drama, comedy, cupcakes and mojitos.

The books are (in order):

(Jane Madison)

Girl’s Guide to Witchcraft

Sorcery and the Single Girl

Magic and the Modern Girl

Capitol Magic

Single Witch’s Survival Guide

Joy of Witchcraft

(Sarah Anderson)

Fright Court

Law and Murder

High Stakes Trial

(David Montrose)

The Library, the Witch, and the Warder

She has also written some vampire books that take place in a Washington, D.C. hospital, and some books with an actress, a magic lamp and a genie, but I am not going there. At least, not today.

Summer reading #3B

Summer continues, and so does the science fiction list. Here are authors M-Z who made my roster of favorites.

Alphabetical, by author’s last name:

MARLEY, LOUISE: The Terrorists of Irustan. The book is set on a planet that was settled by humans long ago, but where the Second Book of the Prophet reigns, where men maintain their dominant male culture and women are not seen outside the home without being wrapped head to foot in veils. The only women who maintain a tiny portion of independence are those who are trained as medicants, the poor excuse for doctors on this planet. (The men find the profession of medicine distasteful.) These women treat the colonists injured in the rhodium mines, and also minister to any others who are sick and injured. One such medicant, Zahra IbSada, makes a controversial personal decision in the course of her duties that will have unexpectedly wide ramifications for the women

on her world.

RUSSELL, MARY DORIA: The Sparrow, Children of God. This is such an odd sci-fi duology; it’s about first contact with extraterrestrial life, but while the United Nations dithers over whether, whom, and when to send a mission to the planet near Alpha Centauri from which has emerged music denoting civilization, the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits of the Catholic Church) quietly puts together a group of eight and sends them off as “missionaries” to the planet Rakhat and its inhabitants.

The story is told from the point of view of Father Emilio Sandoz, who must return from the trip and report back to a tribunal of Jesuits about the fate of the woefully ill-fated group. The book is couched in religious terms, but I wouldn’t exactly call it a religious book; rather, it goes into the complexities of moral behavior and deals with the sometimes devastating knowledge (to the people at the forefront of this contact) that there will be misunderstandings, contradictions, comedy, tragedy, and everything in between if humans go into this interaction expecting “the others” to think and behave as they themselves do.

It’s almost more about anthropology with its concepts of culture and race and behavior. The characters are compelling, the language is mesmerizing, and Russell knows how to create suspense as well as pathos. The story won’t be for everyone—ratings on Goodreads tend to extremes, either five stars or one. But no one can claim it’s not interesting.

SCALZI, JOHN: Various works. John Scalzi has a variety of long series (Old Man’s War, The Human Division, The End of All Things). I have read the entire Old Man’s War series, of which I loved the first few and liked the rest well enough. But my favorites of his are a couple of stand-alones and a trilogy.

The trilogy begins with Lock In, which is a nifty combination of science fiction, murder mystery, and police procedural. A highly contagious virus ravages the world (sound familiar?), and most people experience it as just a mild flu, but for one percent of the population the virus is devastating—it causes “lock in,” wherein the patient is fully awake and aware inside his or her head but unable to respond physically in any way. Technology presents a solution: A method is evolved whereby the locked-in can transfer their consciousness into a robot and thus be mobile and vocal. There is also a less utilized but rather ominous practice whereby the patient can “ride” in another person’s consciousness—the “integrator” is submerged, and the locked-in person dominates the body. You can imagine the implications for solving crime: Who, exactly, was in charge of the person OR the robot when the crime was committed? Rookie FBI agent Chris Shane and his partner, veteran Leslie Vann, are tasked to find out.

The two stand-alones are Red Shirts, whose significance you will instantly comprehend if you are a Star Trek fan (and otherwise don’t bother), and The Android’s Dream. Of the latter, this was my response upon completing the book:

“There are lots of things you can say about books—you can laud the lyrical writing, or compliment the well fleshed-out characters, you can cite the lightning-fast excitement of the pacing—but I would like to pay this book an ultimate compliment: It was one of the most sheerly entertaining books I have ever read. The turn of every page, the beginning of each chapter, led to a more improbable, more hilarious, more ominous, more engaging next one, and it didn’t falter once, beginning to end. It had just enough science in its science fiction to keep things on an intelligent, brain-challenging level; it had just enough philosophy and politics to start you thinking about the what-ifs of human interactions when they are backgrounded by relations with more powerful (and possibly more devious) alien races; it had action, violence, a little romantic intrigue, and a pace that never let up.”

Oh, and I also quite enjoyed his book Fuzzy Nation, which is part of a series but which I read successfully and enjoyably as a stand-alone. I will have to circle back around to his other series some day!

SCHWAB, V. E.: The Villains trilogy. Victoria Schwab is an incredibly prolific 30-something author who has written four or five trilogies and a few stand-alone books, some for Young Adults and some for the rest of us. Most are more classifiable as fantasy, but her book Vicious is a sci-fi masterpiece that consistently stays in my top five. It is so perfect to me that I almost regretted finding out she was writing a sequel, and I just discovered there is to be a third book as well. I am now glad of both of them—I love the way she took the story in #2, Vengeful, and am intrigued by the hints in that book of what will be revealed in #3, Victorious. But whether or not you go on with the trilogy, do consider reading Vicious.

Victor and Eli are college roommates, both of them brilliant above the standard of everyone around them. They decide to collaborate on a research project that involves adrenaline, near-death experiences, and supernatural events, but it evolves into a science experiment, with disastrous results. Victor goes to prison, and 10 years later comes looking for Eli, who has developed his own troubling agenda during Victor’s years away. The characters challenge all your standards for heroes and villains: Victor is the bad guy you love, while Eli is the saint you abhor, and in this book superpowers don’t lead to heroism. The story is elegant, spare, with just the right amount of detail and not an ounce more or less. The fantastic characters come across fully fleshed out in only a few sentences of description. This book is masterful and mesmerizing.

TEPPER, SHERI S. Various works. Sheri Tepper is up there in my list of formidable female science fiction writers, and there is hardly a book of hers that I didn’t appreciate, although I love some much more than others. The ones I will specifically recommend:

The Family Tree: Police officer Dora Henry is investigating three murder victims, all of whom are geneticists. There is a potential civilization-ending catastrophe directly related to these crimes, and Dora is about to find out that her fate is directly entwined with the survival of humankind, with a solution that will reach out to her from a far distant future. Both profound and comical, this is a great book to trigger a rousing discussion of our ecological future.

The Gate to Women’s Country has been dismissed by some as exclusionary second-wave feminism. I prefer to view it as an exciting story with an exaggerated but still valid message. Its subject is the way gender roles have been fixed and cemented for millennia, and where the power should really lie in the battle of the sexes; it portrays a society peculiarly evolved to keep humanity from ever suffering a second wave of nuclear destruction. It is post-apocalyptic, dystopian, and memorable.

The Fresco: Benita Alvarez-Shipton is having a difficult time in her personal life when she is approached in the desert by some aliens asking her to speak on their behalf to the Powers That Be in Washington. She agrees, but then finds herself the sole liaison between the two sentient races, as the Pistach offer the humans a spectacular opportunity for knowledge and enrichment, which the humans typically want to dither and argue about until it’s too late…. This book is both philosophical and hysterical, and I reread it every once in a while just for the fun of it.

The Companions: This is real science fiction—layered, intricate, analytical, examining moral, racial, social, global, galactic issues, all within the context of a story. It deals with humans’ seemingly innate inability to refrain from destroying their own environment, and what happens when other intelligent life decides to stand up for itself. A fascinating read.

JOAN D. VINGE has been a notable contributor to many science fiction anthologies, and has also written some Star Wars novels, but her two original series should be a fan’s focus. The first takes place on the planet Tiamat, beginning with The Snow Queen, which initially reads more like fantasy than science fiction. This is a purposeful choice, however, because the story is told from the perspective of the Summer “primitive,” Moon, a sibyl for her tribe. The bigger story is that Tiamat is a central stargate that has been ruled during its Winter period by a ruthlessly ambitious and fabulously wealthy queen Arienrhod. The planet is not only essential for interstellar travel but is also a secret source of the empire’s wealth and power. But the planet has 150-year cycles, and the galactic stargate to the planet is about to close, isolating Tiamat and putting its rule in the hands of the Summers…. There are three more books, all good, but the first is exceptional.

Vinge’s other fun series is framed as Young Adult, but can be enjoyed by anyone. It features a half-human, half-alien orphan telepath named Cat, an outsider whose only hope is to work for an interstellar government that he fears and mistrusts. There are three books in the series: Psion, Catspaw, and Dreamfall.

I have to mention the formidable JO WALTON, whose books I only discovered a few years back, and whose style and subject matter are as various as they are brilliant. She is not an author that everyone will appreciate, but her audacious creativity is compelling. Her trilogy, Thessaly, begins with The Just City, created as an experiment by the time-traveling goddess Pallas Athene. The goddess is enamored of the writings of Plato, and decides to create a planned community of 10,000 children, overseen by a few hundred adult teachers plucked from all parts of history (past, present and future); the goal is for the adults to use the teachings of Plato to lead the children to become their best selves. Athene puts the commune on a Mediterranean island in the distant past that will, in its future, be destroyed by a volcano, ensuring the eventual obliteration of her experiment. The god Apollo decides to live a human life, coming to the city as one of its children. Things progress for a few years, and then Athene has the bright (?) idea of pulling Sokrates himself out of time and setting his inquiring mind to work in the City that follows his own pupil’s instruction. The result is intriguing, frustrating, exciting, laughable, and also deadly serious for the fate of the experiment. The story is continued in The Philosopher Kings, and concluded in Necessity.

CONNIE WILLIS: Time travel and other stuff. Connie Willis has written some amazing novels, but my favorites among them are her loosely connected series of time travel books. The first is Doomsday Book, in which the Oxford history department has invented a method of time travel and is sending graduate students, appropriately prepped, accessorized, and clothed, back in time for short periods to study the actual events. Kivrin is sent back to the 1300s to do some research on medieval times, but two things go wrong: The first is that she ends up someplace (well, someTIME) different than she was supposed to, and the second is that there is immediately a flu pandemic in present-day Oxford that prevents anyone from discovering the mistake about where/when she was sent for quite awhile, leaving her to her own inadequate devices.

Willis’s second foray into time travel, although still controlled and initiated by the Oxford history department, takes place quite a few years later, when the perils of time travel are more well known and better appreciated, and To Say Nothing of the Dog is also as silly as The Doomsday Book was serious. Only Connie Willis could combine time travel with a French farce in Victorian England, throw in a couple of mysteries to solve, and pull it off.

I found her other two time travel tomes less satisfying: Blackout and All Clear have a World War II setting as their objective, but someone decided that Willis didn’t need an editor, resulting in one mammoth book of more than 1100 pages being split down the middle into two separate books despite the fact that it’s one connected story, presumably both to make it a more manageable size and also to stimulate extra sales for all those who wanted to read the rest of it! I enjoyed it, but the characters’ circular agonizing over whether they’ve irreparably screwed up the historical timeline becomes tedious, and I wished in vain for someone to come along and judiciously trim about 400 pages from its content to make it a better tale.

Other non-time-travel books of hers I have enjoyed are Passage and Crosstalk.

Last but not least, let me mention a fun and thought-producing book by GABRIELLE ZEVIN, called Elsewhere. It’s intended for teens and I read it with my high school book club, but I think anyone could enjoy the premise and the execution. Liz Hall is a 15-year-old girl who has just died as the result of a hit-and-run accident. She wakes up, quite confused, on a cruise ship that takes her to a place called Elsewhere, which turns out to be the afterlife. In Elsewhere, everyone ages backwards until they become infants who are sent down a flume to Earth and rebirth. But Liz is outraged by this fate: She wants to get her driver’s license, go to prom, and grow boobs, for goodness’ sake, not get younger; and living with a grandmother she never met and doesn’t particularly like is equally unacceptable. Watch as Liz attempts to come to terms with this unexpected outcome.

That’s the end (for now) of my science fiction picks to entertain you for the rest of this long, hot summer. I hope you find something (or things) that fulfills your curiosity about our collective or individual futures!

Summer reading #3

Summer continues, and it’s about time I provided another list. This time it will be science fiction, including both classics and some of the new stuff. I haven’t read as much sci fi in recent years (except for dystopian and apocalyptic, which deserve a category of their own) as I did in my younger years, so this may seem like too much harking back to past glories of the genre; but don’t discount the “ancients,” some of their stuff is still ground-breaking. I will attempt to share more of the books that seem still relevant to a speculative future.

Alphabetical, by author’s last name:

ALTEBRANDO, TARA: Take Me With You. A YA novel of technology run amok that could easily happen in our near future. Think about Alexa, already able to a degree to self-program by learning from repeated experiences and providing what you want or need in your home or car. Then give her a little boost, so she is aware enough to become curious about human interactions and to experiment with your reality by trying out things you haven’t requested or approved, with little critical judgment about what is trivial and what is potentially catastrophic. Now you have the propelling idea.

ASIMOV, ISAAC: The Foundation Trilogy. In this trilogy, which later grew to encompass more books both directly and tangentially connected, Asimov imagines a Galactic Empire that has ruled a vast expanse of populated space for 12,000 years. One scientist, Hari Seldon, has created a science called “psychohistory” that he believes projects for humankind a dark age of ignorance, barbarism, and warfare. He resolves to protect the accumulated knowledge of the Empire, thereby shortening and softening the effects of this dark age, so he gathers the best minds in the Empire and creates a Foundation to preserve hope for future generations. But those who would rule—both in the Empire itself and from among the warlords rising to conquer it—are inimical enemies of Seldon and his preservationists, who have to come up with clever ploys to hide, fight, and prevail.

Other books for which the exceedingly prolific Asimov is famous are the Robot series, beginning with I, Robot (nothing at all like the ridiculous movie), and a series of books about the Galactic Empire.

CARD, ORSON SCOTT: Ender’s Saga. Many are familiar with the classic Ender’s Game by this author, but not so many go on to read the subsequent volumes, which is a shame. There are at least five and possibly more books that deserve recognition in this series, including Speaker for the Dead, Xenocide, Children of the Mind, Ender in Exile and, from the directly connected Shadow series, Ender’s Shadow and Shadow of the Hegemon. I’m not a big fan of the other books by Scott that I have sampled, but this is a solid series, taking the reader from a simple view of “the bugs” as an enemy to be mown down in their hundreds of thousands to a philosophical and social comprehension of another race unlike ours but worthy at least of recognition and an attempt at truce.

ELLIOTT, KATE: Novels of the Jaran. An anthropological science fiction story, with overlapping alien races who know about each other but don’t know each other. There are the supposedly indigenous people of the interdicted planet Rhui, who may in fact be distant descendants of the people of Earth, perhaps the remnants of a lost expedition, and who live in a cultural bubble as nomadic hunter-gatherers; there are the people from present-day Earth, who believe it is necessary to preserve the nomads in their ignorance of space travel and other races and peoples; and there are the “aliens,” who once inhabited the planet and whose artifacts have been incorporated into the spiritual beliefs of the occupying nomads. It’s such a fascinating philosophical puzzle, and the intrigue comes from watching them all trying to coexist while keeping their secrets and pursuing their own goals and ideals. There are four lengthy books in the series; if the description intrigues you, you can read a more complete review and explanation here.

GRAY, CLAUDIA: The Constellation trilogy. This is a YA trilogy that deserves to be read on its own merits as an exciting sci fi chapter. The premise is that there are five planets that have been settled from Earth, each one vastly different according to the ideals and expectations of the settlers who colonized it. The books are, in some ways, pure space opera, but because of the examination of the settlements they also go into religion, environmentalism, and politics, and are thought-provoking in all areas.

Noemi Vidal is a soldier defending the rights of her planet, Genesis, from the depredations of Earth. During a battle, she discovers an artifact of Earth, a robot named Abel who has been abandoned in space for decades, but whose ingenious design by his creator has guaranteed his further evolution as a learning, thinking being. His initial meeting with Noemi is potentially cataclysmic, but she turns out to be the catalyst who brings him to ultimate personhood. There is a slow evolution of character, with issues of trust and confidence, that makes this a particularly intriguing read. The books are Defy the Stars, Defy the Worlds, and Defy the Fates.

HEINLEIN, ROBERT: Various books in his universe. Heinlein wrote science fiction from his first short story in 1939 to his last novel in 1988. He was considered one of the first “hard science” writers, in that he insisted that the science in his novels be accurate. He also anticipated many later inventions, including the CADCAM drafting machine, the water bed, and the cell phone. Many of his later books suffer from Heinlein’s rigid (and slightly bizarre) agendas, but his more well known works, as well as many of his earlier ones, are great stories with a unique perspective. Some of my favorites:

The Door Into Summer: Encompasses romance and time travel, as well as the invention of various robots including one that closely resembles the Roomba.

The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress: The Moon has evolved from a former penal colony into a rugged frontier and a source of trade for Earth. But when Earth seeks to dominate the citizens of the Moon, several of them rise up to lead an unorthodox revolution to gain freedom for all its inhabitants—even their secretly sentient computer!

Stranger in a Strange Land: Michael Valentine Smith is a human who was raised on Mars. Experiencing Earth and his own people in adulthood, he struggles to understand their social mores and prejudices and ultimately starts a movement to promote his own philosophy of love. If you have ever heard a nerdy friend say “I grok” instead of “I understand,” you can be sure he has read this significant work of Heinlein’s.

HERBERT, FRANK: The Dune saga. This is a fascinating tale of conquest, witchcraft, indigenous rights, and the mystery of a life-changing substance, Spice, that controls the universe and is only available on this one remote planet. Warring houses—the Harkonnens and the Atreides—struggle for domination of the spice trade, but go about it in radically different ways, the Harkonnens by cruel oppression and the Atreides by ultimate assimilation. Follow the fortunes of House Atreides as the young son of the Duke must come to an understanding with the natives of Dune or die trying. This is a long series; I would recommend the first six books, but after that it gets increasingly odd and obscure. Herbert is not a writer for everyone; his non-Dune books are challenging to read and more so to understand. But the saga he created in Dune is riveting and worth your time. Let me warn you, however: Frank Herbert passed away at a relatively young age, and his son, Brian, took over the franchise. I will be kind and just say, Don’t bother.

JEMISIN, N. K.: The Inheritance trilogy. What a fascinating series. I don’t know how to describe it, because parts of it are so amorphous. It’s full of intense themes–fate, love, death, destiny, chaos, divinity, life—and particularly potent characterizations. I don’t normally like books in which the gods or a god take an active part, but these gods were…something else, both literally and colloquially. I will say that Jemisin is a lyrical writer with an amazing breadth of vision, and the thing I like about this high fantasy series is that it doesn’t follow the clichéd tried and true for one moment. These won’t be for everyone—they are challenging to read—but for some they will be beloved. The books are The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms, The Broken Kingdoms, and The Kingdom of Gods.

LE GUIN, URSULA: Various. I regard Ursula K. LeGuin as perhaps the best science fiction writer of her age. She is perhaps better known for her fantasy series, Earthsea, but her science fiction novels are equally compelling, and written indubitably for grownups. Some of the best:

The Dispossessed: There are various peoples living on a world much like our own, and one group of them wishes to lead a different kind of lifestyle than that to which the rest of the planet, Urras, is committed. So these anarchists leave Urras for Anarres, the moon, which is just barely habitable for humans, and create their own perfectly equitable utopian society in direct contradiction of the capitalist one on Urras. There is an interdiction between the moon and the world—beyond limited trade, which takes place within the boundaries of a landing field on either world, there is no contact between the two for generations. Then Shevek is born on Anarres, and it quickly becomes clear that he is the most brilliant physicist of his generation. His need for interaction with other minds as bright and quick as his own provokes a showdown about the association of the two peoples, and Shevek must choose whether to give up his partner, his child, and his life on Anarres in order to find what he is seeking.

The Left Hand of Darkness: When a child is born on Earth, what is the first question everyone asks? “Is it a boy or a girl?” Now imagine a world where the inhabitants can both choose and change their gender at will, and yourself as the lone one-gendered human (male) emissary from the Hainish empire, sent there to facilitate this world’s inclusion in your growing intergalactic civilization. Imagine the implications of psychology, society, and human emotions when examined in this strange environment. This book is hailed as “a landmark achievement in the annals of intellectual science fiction”—but it’s also a fascinating tale.

Other books noteworthy in what Le Guin called her “Hainish cycle” are City of Illusions, Planet of Exile, The Word for World is Forest, and The Telling. She also wrote a variety of other fiction with a more anthropological bent. In my opinion, everything she wrote is worth reading.

Whoo! This has stretched out way longer than I expected, and we have only covered authors in A-L. I’m going to stop here, publish, and save M-Z for next time. Enjoy your immersion in the speculative world of your choice!

Ginny Moon

I picked up a Kindle copy of The Truth According to Ginny Moon, by Benjamin Ludwig, partly because it sounded like a good story and partly because it was discounted to $1.99 and I was looking for something realistic to bounce back from my prolonged immersion in fantasy.

This is not an easy story to read; I don’t mean that from the standpoint of time or vocabulary, but rather because the heroine, Ginny, is so overwhelmed by frustration at unmet expectations that her constant state of tension, confusion, anger, and sadness, all further accentuated by the characteristics of autism, is hard to bear in prolonged doses. But what kept me reading was knowing that what was hard for me to read must be impossible for Ginny to experience; I almost felt compelled to continue for her sake, as if she was a real person and needed me to advocate on her behalf!

The story opens when Ginny is 14 years old. She grew up in an untenable situation with a flighty, impulsive, irresponsible drug addict of a mother and her dysfunctional rager of a boyfriend. Ginny was removed from the household at the age of nine, when she showed a “failure to thrive” that included malnutrition, bruises, and evidence of broken bones and possibly worse violations in her past. She then went through several foster situations and finally ended up with Brian and Maura, who have adopted her. But the birth of their baby, Wendy, triggers profound and unsettling memories for Ginny, causing a drastic shift in her demeanor that baffles everyone who knows her. Ginny seems to revert to a younger age, obsessing over her Baby Doll that she left behind at her mother’s apartment; she ultimately finds a way to contact her birth mother (who is forbidden to see her) so that she can find out if they found the Baby Doll after she left, and if it is okay.

This initial innocent action on Ginny’s part turns her world upside down, as she tries in vain to communicate her fears to those around her—her new parents, her therapist—while they must deal with the intrusion of the birth mother, Gloria, and others from Ginny’s past, and become increasingly frustrated by Ginny’s continuing erratic and difficult behavior.

I can’t speak to the accuracy of the depiction of autism as expressed in Ginny. I tend to think that a lot of her situation, while exacerbated by the functional issues of the condition—emotional disconnection, apparent lack of empathy, inadequate socialization, extreme sensitivity to external stimuli, compulsive habits—could equally be blamed on PTSD from the unendingly stressful situation in which she was raised. But regardless, she is the fascinating narrator of her own story, and seeing everything from her perspective gives the reader a glimpse into what it must be like to try to navigate the world as such an unusual person. The literalism, the skewed but also sensible logic, the heartbreaking self-analysis as those she loves seem to reject her, all come together to create a truly heroic individual who is confronting her demons despite her despair. Bravo to Benjamin Ludwig for giving this child such a wonderful voice.