Christmas past

I find myself, on the 18th of December, woefully unprepared to offer up Christmas reads here on the blog. I haven’t exactly been busy, but I also haven’t been much in the holiday mood, so I have read nothing relateable to share. But I did do a search on my own blog, which I encourage you to do as well if you are in need of a festive book to read, and found a bunch of suggestions I featured from Christmases past. Just put “Christmas” in the search box and you will find at least five separate lists.

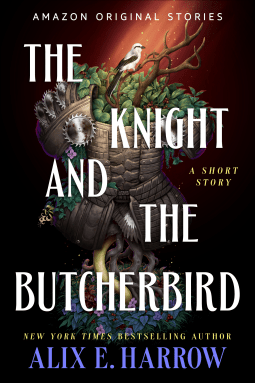

In case you are too lethargic to do that, here’s one that I mentioned before and will share again—a novella with minimal effort and maximum payoff from one of my favorite authors, sci fi writer Connie Willis. I knew that Willis herself collected Christmas stories, having come across a comprehensive list she made some years ago of all her can’t-miss favorites, but I didn’t know she had written one until a few years ago.

Take a Look at the Five and Ten is pure nostalgia in its subject matter while being scientific in its methodology. It adopts the premise of her book Passage, wherein a neuroscientist is conducting research on a particular aspect of memory. In that book it’s all about dreams, while in this one the topic is the TFBM: Traumatic Flashbulb Moment. A Ph.D. student, Lassiter, is doing a study of people who have experienced one of these; imagine his delight when he meets a new and potentially perfect subject at Christmas dinner with his new girlfriend’s family.

Ori begins dreading each year’s holiday season (Thanksgiving to New Year’s Day) in July. Her one-time stepfather, Dave, never lets go of the people from his past, so even though he’s working on his sixth marriage (his union with Ori’s mom ended when she was eight years old)), he never forgets to include in his celebratory invitations the in-laws he collected along the way, including Ori, Aunt Mildred (the great-aunt of his second wife), and Grandma Elving (the grandmother of his fourth). Dave’s latest bride, Jillian, cooks elaborately awful trendy food, and invites her snotty daughter Sloane, along with Sloane’s current boyfriend and her own stuck-up friends, and they all, with the exception of Grandma Elving, treat Ori as if she is a combination of charity case and the hired help.

Grandma Elving presents her own trying behavior, as she insists on telling the same story each year of how she worked at F. W. Woolworth’s “five and dime” store in downtown Denver one Christmas in the 1950s. Everyone else in the family is fed up to the gills with hearing it, but Sloane’s new boyfriend is fascinated by Grandma’s extraordinary ability to remember each and every vivid detail about her experiences at Woolworth’s, since clarity and consistency of a particular memory are hallmarks of a TFBM. Lassiter invites Grandma to be one of his test subjects, and the two of them elicit assistance from Ori to get Grandma to and from her appointments at the clinic where Lassiter is conducting the experiment. Ori quickly begins to have what she knows are ill-fated feelings for Lassiter as their proximity grows….

This is a cute and humorous Christmas tale reminiscent of the French farce-like quality of Willis’s time-travel book, To Say Nothing of the Dog. It’s short (140 pages), qualifying more as a novella than a full-length book, and you can get it for Kindle too, so if you’re trying to hit your 2025 Goodreads Challenge quota, it’s a quick read that counts. But best of all, it’s an unconventional Christmas story that will give you even more appreciation for Willis’s whimsy and heart.

Age and time

After 900+ pages of frustrating and confusing murder mystery, I needed a break from the serious, so I picked up two books in a row by Sophie Cousens, whose books are billed as romantic comedies. I don’t know that I would go that far, although there are comedic elements and/or moments. But I did find them enjoyable, one more than the other, although the one I liked second-best is apparently her most popular.

First I read Is She Really Going Out With Him?, mainly because I am a big fan of Joe Jackson. If you don’t get that reference, you are probably too young—Joe made his mark in the 1970s. But do go to Spotify and dial up his song by the same name—you might find a new favorite musician, who knows? If you like the song, then follow up by playing his album Night & Day.

Anyway…the premise of this one is engaging, although you sort of know what will happen at the end by pretty early on. Still, it’s amusing the way the story takes you there. It’s the tale of a divorcée with two children and not much interest in (or success with) renewing the dating game. Anna is a columnist for a popular but struggling arts magazine that has just been bought by a larger company, and she’s nervous that her job is on the line; the new publisher wants material that is more social media-attuned than her traditional approach—more personal, more anecdotal, more relateable. She is doubly alarmed when she gets the idea that her office rival, Will, may be trying to poach her column.

She ultimately has a contest of sorts with him, when he proposes to the publisher that they do a dual column. Anna decides that Will will write about going out with seven women he discovers on dating apps, while Anna will give up the details of the same number of dates with men chosen by her children. Since they are young and enthusiastic (seven and 12) and not particularly discriminating in their choices, her dating pool is a weird one, but Anna gamely holds up her end of the competition. But working together with Will presents more problems than just fending off his job takeover…

Yes, it’s pretty trope-y, and yes it’s been done before, but Cousens does have a gift for character development and for comedic moments that keep this one pretty fresh. And yeah, an author who references Joe Jackson…

The second book, The Good Part, reminded me of a few other books (in a good way), foremost being What Alice Forgot, by Liane Moriarty. In that book, Alice gets conked on the head and forgets about the past decade of her life, in which significant things happened (she had kids, she got divorced), which makes it awkward and sometimes comical when she keeps trying to relate to people the way she did in the moment to which she has been returned by amnesia. The Good Part is sort of the opposite of that, because Lucy Young doesn’t forget her past, precisely, she just anticipates her future so hard that she suddenly wakes up there one morning.

Lucy is 26, a downtrodden TV production assistant who is tired of fighting for the promotion that never comes, tired of living in a dump with three inconsiderate roommates and a ceiling that leaks on her bed every time the upstairs neighbor takes a bath, and one night when she takes shelter in a news agent’s during a downpour and discovers a curious wishing machine, she puts a coin in the slot and wishes hard to be past all this and into the “good part” of her life.

Next morning she awakens with a ring on her finger that the handsome man downstairs apparently put there, and a closet full of really expensive designer shoes. But she also has two children about whom she has no memory, a high-powered job she doesn’t know how to do, and a shockingly old (40-something) face confronting her in the bathroom mirror! She has apparently been transported ahead 16 years but retains only the memories of her life up to age 26, which in her mind was last night.

Not wanting to be diagnosed as mentally ill, she tries for a while to “fake it until she makes it,” but with variable success (especially with her older child, who thinks an alien has possessed his mummy). At first she firmly believes that the mysterious machine has transported her here, and that she will wake up the next day back in her grotty apartment, but when this doesn’t happen, she also has to confront the idea that she may simply have amnesia and has conjured a crazy reason for it.

The most interesting part of the book is Lucy’s inner debate about what she really wants. She has it all—but at the cost of missing the entire experience of getting there. Her husband remembers them falling in love, the birth of their children, her climb up the professional ladder, but inside Lucy is still that single girl who has never been able to afford nice things, doesn’t know if she wants to have kids, wonders if she should ditch her career for something different…and now that she is seemingly in the middle part of her life, she has to decide whether she will settle into the wonderful achievements and relationships she doesn’t remember establishing, or try to get back to her past so she can experience them all first-hand—or possibly make different decisions? This quandary is complicated by the fact that what she ends up doing (if she is able to figure out how) may impact not just the lives but the very existence of the husband and children staring at her with so many questions in their eyes…

These books were a great way to while away a few days. I might even read more Cousens the next time I get burned out on long, serious, and complicated.

Water, water everywhere

I love dystopian and post-apocalyptic novels. I have a fairly long list on Goodreads of those I have already read, and I continue to look out for others amidst all the book recommendations I see online. Included in my favorites are A Boy and HIs Dog at the End of the World, by C. A. Fletcher; Starhawk’s Maya Greenwood trilogy set in San Francisco about the division of California into the good, bad, and ugly that includes The Fifth Sacred Thing (the best of the three); the seemingly neverending post-nuclear-war saga detailed in Obernewtyn and sequels by Australian writer Isobelle Carmody (that has taken her decades to complete); the weird and horrifying Unwind series by Neal Shusterman; and a few oddball stand-alones such as The Gate to Women’s Country and The Family Tree, by Sheri S. Tepper; Lucifer’s Hammer, by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle; and War Day, by James Kunetka and Whitley Streiber. I have about two dozen more on my list, and probably that many again that I still want to read. But Kassandra Montag’s After the Flood crossed paths with me purely by accident.

In December, I found a vendor on Etsy who put together cute “blind date with a book” packages including bookmarks, teabags, and a book, and thought this would be the perfect Christmas gift for a friend who seemed to be in an emotional slump; so I purchased the package and told the seller what book I would like her to include. Her response was to say that she didn’t take specific requests, but would try to accommodate if I gave her a list of preferred genres and some example titles. I felt that her advertising had been misleading, but ultimately went along with the program by giving her my friend’s favorite genres (romance and science fiction), with my sole request being that she send an upbeat story, since the whole idea was to cheer up my friend. Her choice was this dystopian novel by Montag, whose description alone should have warned her off.

After apologizing to my friend for this weird choice, I decided that I would read it myself to see just what she was in for; and after having finished it, I can say that it’s wholeheartedly depressing and that I’m really wishing I could get my money back. Not so much for me, but it definitely won’t be lifting my friend’s mood!

It’s set about 100 years in the future, when global warming has (presumably) done its worst…

We still called oceans by their former names, but it was really one giant ocean now, littered with pieces of land like crumbs fallen from the sky.

The ice caps melted and the water rose, first engulfing the coastlines and then, with the Six-Year Flood, the flatlands were likewise covered by water, and the remaining land consisted of mountaintops sticking up above the watery horizon. People fought to cling to the small settlements carved out of those elevated spaces, or they took to the water, living their lives on the sea and only docking to trade fish for vegetables, flour, fabric, and materials to repair their boats.

Myra and her daughter Pearl are eking out a precarious existence on their boat Bird, built by Myra’s grandfather when the water began to overwhelm their Nebraska farm. Myra’s husband Jason was so terrified of the encroaching floods that he decamped in a friend’s boat, kidnapping their five-year-old daughter, Row, while Myra was in her last month of pregnancy. Her grandfather and her mother didn’t survive the floods, and Myra was forced to set sail when Pearl was an infant still carried swaddled on her mother’s chest.

Now it’s seven years later, and Myra and her daughter are living day-to-day, keeping their heads down, avoiding other people for fear of their intentions. But one day Myra encounters a raider who inadvertently gives her news she never expected to hear; her older daughter, Row, is still alive, in a settlement up in Greenland. This hopeful news is offset by his comment that she’s nearly old enough (13) to be sent to a “breeder” ship, which is exactly what it sounds like; and Myra becomes determined to go and get Row, whatever it takes, to protect her from this fate.

Unfortunately, luck and nature are against her, and she has to team up with others to pursue her goals. But how many people is she willing (or right) to endanger to get what she wants?

The world-building in this book is excellent: visceral, realistic, and detailed. The disintegration of the moral integrity of desperate people also rings true, and many of her characters are compelling. But…there were a few things that work against elevating this to among my favorite dystopian novels. I found myself disliking the main character quite a bit for her ever-shifting moral compass and especially for all her justifications; so living inside her head in order to follow the story proved both exhausting and occasionally distasteful. And while the synopsis given by the publisher promises to serve up hope along with the angst, it seems like there is pitifully little room for that amidst all the catastrophe, and I didn’t feel like the end of the story justified the means.

Still, it was fairly engrossing, especially in the action-packed parts, and it also painted a poignant picture of the joys, the pains, the requirements of motherhood. So I would recommend it as a solid dystopian tale, but I wouldn’t rank it in my top ten.

Impossible

I picked up this book mainly because I thought I had read Matt Haig’s previous book, The Midnight Library. And at some point I must have actually believed I had read it, because I gave it a five-star rating on Goodreads. But there is no accompanying book review, which is unheard of for me since about 2012, so I looked through all my back posts and discovered that I had planned to read it, but somehow ended up instead with The Left-Handed Booksellers of London, by Garth Nix!l Anyway, that means The Life Impossible is the first book by this author that I have read, which means I came to it under false pretenses.

I may still read The Midnight Library, because I did enjoy parts of this one, and that one is better, according to the reviews of countless others.

I was initially drawn to this one by the description, which was about Grace Winters, a retired teacher who has been experiencing a dreary sameness to her days. (I related to this, being a retired librarian of a certain age who is mostly housebound.) Then she discovers that someone with whom she had a brief friendship decades before has left her a house on the island of Ibiza (one of the Balearic islands off the coast of Spain in the Mediterranean). There is some mystery about what happened to this friend—she is presumed dead, but no one can give Grace a clear account of how—and Grace decides, impulsively, to go to Ibiza and find out.

Up to that point, the story seemed like it was going to be one of those books where somebody who is stuck hits a turning point and changes her life, and that is, indeed, Grace’s story; but the magical bit to this tale isn’t that she discovers herself by embracing a different lifestyle in a fresh locale, or that she meets someone or acquires a new and exciting avocation. The magical bit is, indeed, magic—it’s something that is described by those who introduce her to it as a natural phenomenon that is the next step along the way for the evolution of humans’ innate powers or abilities that just looks like magic. And the explanation of its source is even more bizarre. So, this is a story for which you have to be willing to suspend disbelief, which at some moments feels easy and natural and at others may cause you to say “What?!” and put down the book.

I don’t know whether to characterize this story as magical realism or as a metaphysical metaphor or what. It has some uplifting and ah-hah moments, but I had as hard a time embracing them as Grace does. I appreciated the setting and the beautiful descriptions of Ibiza, about which I have been fascinated ever since I read about the place in a Rosamunde Pilcher novel 25 years ago, and I liked the eco-consciousness the author promotes; but some of the elements of the story were just too weird for me, and the narrative becomes borderline didactic in its zealous promotion of self-actualization.

Also (and some may find this too nit-picky, but so be it), I didn’t like the vehicle that caused Grace to write down her saga: She receives an email from a former student who is having a really hard time—Maurice has lost his mother, lost his job, been dumped by his girlfriend, and is in despair—and instead of doing something concrete to assist him, such as sending him an encouraging response, or engaging in a series of helpful phone conversations during which she listens and is supportive, or referring him to a therapist and following through to make sure he is okay, she makes it all about herself. She tells him “I know what you’re going through” and then writes a 300-page manuscript about her own issues and how she resolves them, and sends it to him as if that will somehow fix things. I mean, he might find that it briefly diverts him from his own problems, but short of going to Ibiza himself and trying to replicate her experience, it certainly doesn’t address his crisis, particularly because what did happen to her could cause him to think she’s lost her mind.

Hmm. Have you ever started out writing a book review thinking that you had enjoyed the book and discovered, by the time you dissected all of its elements for your readers, that maybe you weren’t so thrilled by it after all? Yeah. Well.

Positives:

• Some truly epic descriptions of the character and beauty of the island of Ibiza

• Some engaging characters

• A protagonist with whom some may closely identify (at least initially)

• A useful portrayal of how capitalism is destroying nature

• Some lyrical writing and a few memorable moments and quotable quotes

Negatives:

• A lot of angst and some petulant indignation

• Meandering narrative that prolongs the story to no purpose

• Magical elements that start out appealing but end up being pretty weird

• A certain self-centeredness on the part of the protagonist and several of the other characters

I guess you will have to decide for yourself on this one.

Reiteration

I got frustrated this week by my seeming inability to pick a winner of a book, and fell back on a sure thing by rereading Charlaine Harris’s four-book series about Harper Connelly, victim of a lightning strike, who uses the ability given her by this event to make a new life for herself. And now, once again stymied by a new-to-me book series that isn’t grabbing my attention or enthusiasm, I’ve been considering rereading Harris’s other series about dystopian gunslinger Lizbeth “Gunnie” Rose. So imagine my delight, after going to Goodreads to remind myself which book was first in the trilogy, at discovering that Harris wrote two more in this series while I wasn’t paying attention!

If you’d like a more thorough dissection of these two favorite series of mine by Harris, go here and read all about them. This post reviews the third book in the Gunnie Rose series. And stay tuned for reviews of The Serpent in Heaven, and All the Dead Shall Weep.

Diversity and superheroes

I just finished reading two books of a planned trilogy by April Daniels. I would slot them as young adult although, in the area of superheroes, fandom seemingly crosses all borders, including that of age. But since the protagonist is 15 when book #1 opens, and comes with a lot of the issues teens encounter, labeling them YA is plausible, whether or not the author intended that.

Dreadnought (Nemesis #1) follows the adventures of Danny Tozer. When the book opens, Danny is Daniel, an unhappy teen girl trapped in a boy’s body, with parents who adamantly refuse to see her for who she is or even contemplate the possibility of a transgender future. A miracle is shortly to follow, however; while hanging out alone behind the mall, Danny ends up on-scene at the murder of Dreadnought, a powerful superhero, and as he dies he passes the “mantle” of his powers to Danny. What comes with those powers is a transformation so epic that Danny’s life will be forever changed—she is gifted with a girl’s body as part of her new identity. Although becoming a superhero ought to be the most amazing thing that happens to a person, it is the realization of her secret dream of manifesting as female that is the overwhelmingly joyous news.

But Dreadnought was taken down by a “black cape” named Utopia, who shouldn’t have had enough power to faze him, let alone kill him, and now Danielle has to figure out how that happened and foil Utopia in her grand plan for the destruction of humanity. And she will have to do so while confronting the prejudice and paranoia of her parents, whose dearest wish is to find a “cure” that will turn her back into “their son,” a disillusionment regarding her best friend, who turns out to be an objectifyer when Danny turns into a girl (hey, eyes up here, dude) and, of course, her fellow superheroes in New Port, some of whom also have a problem with Dreadnought suddenly being a 15-year-old petite blonde.

This is such a fresh, wonderful, fun, and yet serious discussion of transgender in the context of fiction! The author shares the identity of the underrepresented and marginalized group in question, and in this series, the authenticity shines through. There is something for everyone here: While those who enjoy the cool powers, the fight scenes, and the trope of conflict between good and evil so characteristic of superhero books can revel in those things, there is also a lot of all-too-mundane psychology tied up with the issues of misogyny, abuse, identity, gender vs. sexuality, you name it. In addition to the transgender nature of the protagonist, we have her lesbian love interest, a non-binary superhero colleague, multiple people of color, and a villainous trans-exclusionary “feminist.” But none of these (well, with the possible exception of Graywytch, who turns into kind of a cipher as the plot progresses) is a stereotype: Danny runs the gamut of emotions—brave, terrified, powerful, weak, utterly secure, and totally lacking in self-confidence. The side characters are equally well developed, especially those who are in her inner circle of supporters and colleagues. The world-building is thorough, and especially enjoyable is all the focus on “hypertech” inventions.

I enjoyed the first book a little bit more than the second, simply because I love a good origin story, and Dreadnought dealt much more with the emotions and challenges of a 15-year-old transgender girl who is suddenly in the spotlight as the heroine of the city and has to work through all her personal issues with family and friends while simultaneously maintaining a public image and fighting crime. Sovereign landed more heavily on the superhero role and focused less on the personal, although it almost made up for it with the relationship dynamics among the main characters, including a little romance. And the ongoing question of the wisdom of taking a survivor of childhood abuse with anger issues and encouraging them to beat up on people (well, admittedly bad guys, but still) is also a powerful theme.

Having read these two, I would have felt completely satisfied with a duology; but Daniels is writing a third book to wrap up the secondary plot of Nemesis, and I look forward to reading it. This is a solid recommendation for a positive and delightful treatment of diversity within a fictional shell, not to mention a dynamic story line and an enjoyable read! I would suggest this for teens 14 and up, plus anybody who enjoys a good superhero tale. To discover other diverse books, visit https://diversebooks.org/.

Genre assumptions

The book I chose to read this week was the perfect example of being led into genre mislabeling by certain aspects of content. The book is Dragon and Thief, by Timothy Zahn, part of the “Dragonback” series. Because of the presence of dragons, and also because of the series title (making it sound like people were riding on the backs of dragons), I assumed going in that this would be a fantasy. After all, dragons are mythical creatures, right? and their presence would probably indicate world-building that involves some kind of medieval setting?

I was dead wrong. The only thing I got right about this book was believing that it would be a solid addition to my list of books for middle school readers, and that I might possibly be fortunate enough to have discovered one that was particularly appealing to boys, who are more typically reluctant readers than are girls at that age.

Dragon notwithstanding, this is science fiction. The dragon is one of a race of poet/warriors (the K’da) who are symbiotic with other select species and need them in order to live. The dragons transform from three dimensions to two, and ride around on (and receive sustenance and life from) their hosts while giving the appearance of being a large and elaborate tattoo—so instead of people riding dragons, it’s the other way around. And all species involved in this book are space-faring, with much of the action taking place on ships and in spaceports and outposts on various planets.

There aren’t too many books with dragons that anyone would consider sci-fi; the dragons of Rachel Hartman, for instance, while able to shapeshift back and forth between their native shapes and human form, are set within a construct that is definitely medieval in nature, as are the conflicts explored in her books. Same with the dragons of Robin Hobb, Robin McKinley, Chris Paolini, Jasper Fforde, and, of course, Tolkien. Even Naomi Novik’s Temeraire books, alternate history in which dragons are the steeds ridden by the soldiers of the Napoleonic Wars, figure more as fantasy than anything else.

The only dragon books of which I’m aware whose author has attempted to claim science fiction status are those of Anne McCaffrey. Since these are telepathic fire-breathing dragons that bond for life with their riders, many have scoffed at McCaffrey’s claims. Her rationale for the premise is that mankind travelled to the planet Pern via rocket ships, only to discover that their new home was beset by deadly spores that traveled from a red planet to theirs in irregular cycles that lasted a decade or two every once in a while; they used their science to take the native fauna they called fire lizards (miniature dragons about the length of a forearm) and super-size them through selective breeding to wipe out the spores by breathing fire on them. (Her premise would be a lot more believable if she had also thought to use science to explain how these spores from the red star survive the unbearable heat of entry into the planetary system only to be destroyed by a simple toasty breath!)

Anyway, back to my middle school series. Zahn’s voice is perfect for his protagonist, who is a 14-year-old thief named Jack. Jack’s parents died when he was little, and his uncle Virgil, an interstellar conman, raised him to be an innocent-looking but precocious assistant for his various illegal exploits, so Jack has lots of talents like breaking and entering, computer program manipulation, and being a quick-thinking fast-talker. But his uncle died a little while back, leaving Jack alone except for the computer that runs Jack’s ship, upon which Uncle Virgil imposed his personality, so that “Uncle Virge” is still in some sense with Jack, imbued with the same sly, evasive, self-serving qualities that his human uncle possessed.

Uncle Virge is unhappy, therefore, when Jack decides to rescue and play host to Draycos, one of an advance team of K’da warriors who landed on a supposedly vacant planet where his people were intending to settle, refugees hiding out from their mortal enemies. Somehow their enemies already knew their destination, however, and managed to destroy all the advance ships and everyone on them save Draycos. Draycos has a few months to figure out what happened and from where, exactly, the threat lies, so that he can return to the main emigration ships of his people and re-route them somewhere safe, and Jack has undertaken to help him.

It turns out, however, that Draycos is at least as helpful to Jack as Jack is to Draycos, given his superb warrior skills. The two of them make a good team—the boy with lots of undercover experience to get them where they want to go with no one the wiser, and the dragon, honorable and principled, who can protect them along the way.

I finished book #1 and proceeded on to the second, Dragon and Soldier, and I plan to keep going with the rest of the series. So far, book #2 is as imaginative and delightful as was the first, my sole complaint being that each book ends rather abruptly so that you feel an immediate need to access the next volume, which is actually a decided advantage when it comes to luring the reluctant reader to keep going. I believe that those middle-schoolers (and anyone who loves science fiction and/or dragons) who discover these books will do just that.

Paper magic

I began reading The Paper Magician, by Charlie N. Holmberg, with great anticipation—as it turns out, too great. Its opening pages reminded me of another series (of which I have read the first two) that I recently loved (and reviewed here), the Art Mages of Lure books by Jordan Rivet, beginning with The Curse Painter. They seemed like similar systems of magic, in which the practitioner invests everything in learning how to bring magic to the world through a particular medium, in that case paint and in this, paper.

In this series there is a particular magical system, in which potentials attend the Tagis Praff School for the Magically Inclined and (ideally) by the end of their studies have discovered with which material or element their skills are best-suited to work. Ceony Twill has graduated at the top of her class with every expectation of being able to choose her path as a magician, and her inclination is towards becoming a Smelter, a worker of bullets, jewelry, and all things metal. Instead, she is informed by her mentor that there is a severe shortage in the world of magicians who can work with paper, and she is therefore being assigned to a Folder for an apprenticeship in paper magic.

Ceony’s level of dismay is more understandable when you realize that once a magician chooses a material with which she will bond, that is her medium for life—there’s no changing over to a different field in this system. Still, her new mentor/trainer, Magician Emery Thane, has much to forgive in her first few days as she in turn exhibits reluctance and indulges in sarcasm and sheer petulance. But as he pursues his rather quirky methods of instructing her in the folding of paper into marvelous creations with all sorts of uses (and also none, save for beauty and whimsy), Ceony is gradually won over to the idea that being a paper magician might have its own appeal.

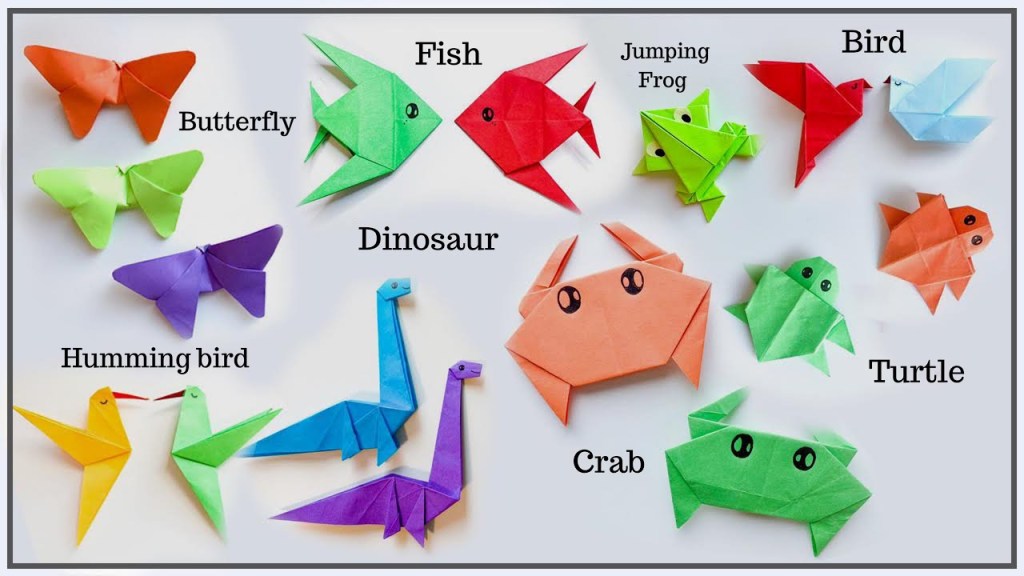

I loved the book up to this point. The idea of binding to a specific material and only casting through that medium was intriguing, and the initial instruction by Mg. Thane (don’t you love that abbreviation?) in how “folding” works was wonderfully portrayed. Consider if you could use origami techniques to fold a paper crane—or a dog, or a dinosaur!—and, if you’d done it perfectly, being able to say “breathe” to it and bring it to life, or at least to animation. Imagine creating an entire garden out of folded paper tulips that would go back to bud every night and bloom again in the morning, or folding a paper airplane that you could actually use to fly across town.

I also loved the grounding of the book in the transitional period between the Victorian era and the Industrial Revolution. Some houses have lightbulbs while others still use gas lamps, or candles. Some drive automobiles while others rely on a horse and buggy for transport. And alongside all this mundane detail, being a magician is equally common—just another job in the world.

Unfortunately, as intrigued with the job of paper folding as she was rapidly becoming, Ceony was also in short order beguiled by the smiling green eyes of her teacher, Mg. Thane. I sighed a little and prepared to be treated to some insta-love alongside the solid characterizations and nice set-up in world-building that Holmberg had created…and then everything went to hell in a handbasket, as people in the 1870s might say.

Why the author chose to hare off on the tangent she did, especially in the first book of the series, is a mystery to me. Suddenly Thane’s ex-wife pops into the picture as a super-villain who takes over the story, even though we have previously never heard of her and are abruptly informed of her ill will towards Thane, his attractive pupil and, in fact, pretty much all and sundry, with a few short sentences about the kind of bad magic she practices; but we have no background on her history, motivations, or abilities. And we are not destined to get any! Instead, she attacks Thane, and Ceony embroils herself (despite being only a couple of weeks into her apprenticeship) in an attempt to save him. Those efforts take up the rest of the book.

I know this is a little spoiler-y, but honestly, I was so exasperated by the turn things took that I couldn’t get over it! There are three more books in this series, although by reading the descriptions it seems like #4 is an add-on; the first three are centered around these two protagonists (Ceony Twill and Emery Thane), while the last seems completely detached per its description. The other books reveal more about the magical system, in that they address people who are able to work glass, plastic, etc., and I am a little tempted to keep reading because of that aspect…but the set-up for book two has Ceony pining over her as-yet lack of attachment to Emery, and I just don’t know if I’m up for it, particularly since there are also promises of a repeat of book one: the introduction of a rogue character who upsets the apple cart again.

I’m not telling you not to read these books; the characters are appealing, and the situations, despite their lack of context, are imaginative. But when I compare this series to the afore-mentioned one by Jordan Rivet, there’s just no contest; and I could wish that this writer had had a more astute editor to say “stop, wait, think” when she decided to take a turn for the dramatic, and point out a more logical, integrated way to pull it off.