Cold cases

I was a little wary when starting to read Case Histories, by Kate Atkinson, because I read her book Life after Life and, while I admired it, didn’t enjoy it much. But I think, in Jackson Brodie, she has found an anchor around which she can wrap the chain of her storytelling to keep it stable.

I will admit that it took me a while to get into this book and to understand what was going on; Brodie is a private investigator who has been invited for various reasons by family members or interested parties to look at three cold cases, the latest one already 10 years past, the oldest more than 30. Because Atkinson presents the case histories one at a time at the beginning of the book before ever mentioning Brodie’s name, profession, or involvement, the book initially seems disconnected by its three narratives, save for the fact that some crime has been committed in each. But having the case histories narrated by the people involved, rather than exclusively through the eyes of Brodie, makes the stories that much more powerful, and also allows us to encounter them as if we were standing in Brodie’s shadow, listening in and trying to make connections in the same moment he is.

I will admit that it took me a while to get into this book and to understand what was going on; Brodie is a private investigator who has been invited for various reasons by family members or interested parties to look at three cold cases, the latest one already 10 years past, the oldest more than 30. Because Atkinson presents the case histories one at a time at the beginning of the book before ever mentioning Brodie’s name, profession, or involvement, the book initially seems disconnected by its three narratives, save for the fact that some crime has been committed in each. But having the case histories narrated by the people involved, rather than exclusively through the eyes of Brodie, makes the stories that much more powerful, and also allows us to encounter them as if we were standing in Brodie’s shadow, listening in and trying to make connections in the same moment he is.

I liked Jackson Brodie’s character, and the slow reveal of what his life is like and what kind of person he is. I also enjoyed the many and varied characters who took the lead in each of the histories, although I did have to scroll backwards on my Kindle a couple of times to remind myself of exactly who they were or how they were involved. Each of the mysteries consisted of equal parts frustration and intrigue, just enough so to keep me reading. But I don’t mind some complexity in a plot, if it serves the plot, which this absolutely did.

I have placed a hold on the next Jackson Brodie book at the library.

READERS’ ADVISORY NOTES: I think this book (and perhaps the rest, we shall see) would appeal to readers of such mystery icons as Ruth Rendell, Barbara Vine, and Patricia Highsmith. Perhaps also Tana French? Those writers produce dark, devious, complex mysteries in sophisticated language, and Atkinson nearly rivals them. And if you are a reader who enjoys Atkinson’s books but haven’t ventured back into the annals of these other writers, by all means do so!

Heroes

It’s hard for me to review Robin McKinley books, because although they have (sometimes many) obvious flaws, the beauty and fluidity of the language and the tangibility of the setting and characters is so overwhelming that I am always mesmerized by it.

In The Hero and the Crown, Aerin is the daughter of the king of Damar, a country that has been led in previous centuries by woman rulers…but the thought of Aerin as ruler of Damar is laughable to anyone who knows her—shy, clumsy, inept, magically ungifted, and daughter of a witch woman from the North who, it was rumored, cast a spell over Damar’s king to insinuate herself into its royal line. Aerin grew up with the story that her mother turned her face to the wall and died in despair when she discovered she had borne a daughter instead of a son to King Arlbath. Her jealous and vindictive relatives, who wish they were the sol of the kingdom instead of in second or third place, never let her forget this story or her own shortcomings. Aerin is essentially alone, with support from her serving woman, her cousin Tor (who is slated to inherit), and her distant but fond father.

In The Hero and the Crown, Aerin is the daughter of the king of Damar, a country that has been led in previous centuries by woman rulers…but the thought of Aerin as ruler of Damar is laughable to anyone who knows her—shy, clumsy, inept, magically ungifted, and daughter of a witch woman from the North who, it was rumored, cast a spell over Damar’s king to insinuate herself into its royal line. Aerin grew up with the story that her mother turned her face to the wall and died in despair when she discovered she had borne a daughter instead of a son to King Arlbath. Her jealous and vindictive relatives, who wish they were the sol of the kingdom instead of in second or third place, never let her forget this story or her own shortcomings. Aerin is essentially alone, with support from her serving woman, her cousin Tor (who is slated to inherit), and her distant but fond father.

But accident and destiny combine to push Aerin out of the shadows and enable her to become the hero of her own story, as well as the savior of her people, the bearer of the blue sword Gonduran and the rescuer of the lost crown of Damar.

This book is a wonderful evocation of an uncertain girl lacking confidence in herself, alienated from all those “normal” people around her and painfully aware of her outsider status, but despite her self-doubt persisting in learning, growing, bettering herself, and turning into a champion in the truest sense of the word. Some of the other characters are slighted a bit when it comes to character development, but McKinley makes up for it with the personality and charm of Aerin’s elderly, injured warhorse, Talat, whose progress mirrors that of Aerin as they quest together.

Two major flaws I see in this book: The abrupt appearance and understanding of Luthe as a character is more than a bit bewildering; and McKinley yanks the bad guy out of a hat, never having mentioned him before, never speculating on his existence, his intentions, or his power, and then gives him one big scene in which he is defeated, somewhat accidentally! As another reviewer on Goodreads mentioned, if you asked readers of Lord of the Rings who Sauron was, they would all know; but with this guy, it’s hard to even recall his name being mentioned, let alone how he came about and the purpose for his existence.

But…despite her glossing over some details that in another writer would be fatal mistakes, McKinley’s prose and imagery and the sympathetic characters upon whom she does focus make this book a triumph.

Although she wrote The Blue Sword first and The Hero and the Crown second, this book takes place some centuries before the events in The Blue Sword, so you can read them in either order. And if you love high fantasy and were charmed by this book, you should definitely read the other one set in Damar, about Harry Crewe, the unlikely heiress to Gonduran. I don’t love Robin McKinley’s books equally–some are amazing, some are okay, and one or two I actively dislike—but The Blue Sword is one of her best.

Although she wrote The Blue Sword first and The Hero and the Crown second, this book takes place some centuries before the events in The Blue Sword, so you can read them in either order. And if you love high fantasy and were charmed by this book, you should definitely read the other one set in Damar, about Harry Crewe, the unlikely heiress to Gonduran. I don’t love Robin McKinley’s books equally–some are amazing, some are okay, and one or two I actively dislike—but The Blue Sword is one of her best.

READERS’ ADVISORY NOTES: These books would most likely appeal to someone who enjoyed Laini Taylor’s Strange the Dreamer, Kristin Cashore’s Graceling realm books, Melina Marchetta’s Lumatere Chronicles, or some of the books of Margaret Mahy and Patricia McKillip. These books all share protagonists who are unlikely as the heroes of their own tales but who manage to rise to many challenges, and all these writers are in some sense wordsmiths of high fantasy language. For those who love fantasy (or those who are recommending it), it is always a smart idea to look to the books of the past as well as to the hits of today.

Bellman & Black

As I mentioned in my Hallowe’en/ Samhain post,

I have been reading Bellman & Black, by Diane Setterfield. I anticipated enjoying this book greatly, based on my experience of The Thirteenth Tale. Unfortunately, that anticipation was misplaced. In most book reviews, I hesitate to give away too much, but in this instance it doesn’t make a difference in your experience of the story. I will reserve the ending.

You get the highlights in the book description on the dust cover. When he is a boy, William has three other friends—all born in the same month of the same year—with whom he runs and plays. As boys did in Victorian England, one of their pastimes is to shoot at things with slingshots. One day William lines up an impossible shot aimed at an immature rook perched in a tree and, against all odds, he hits and kills it. Then there are ominous pronouncements about how rooks never forget, rooks are smart, rooks will avoid you if they perceive you as evil, etc.

Drawing of slingshot © 2019 courtesy of Mishu Bogan

William grows up, forgets about this incident, is taken on at his uncle’s mill, and discovers that he has an uncanny sense of how to better a business. He revamps everything about the mill, endearing himself to both his uncle and the workers. When his uncle dies, the heir, his cousin Charles, an amateur painter and art collector who prefers to spend his time in Italy, lets William get on with running the business for a large share of the profits. He does well, takes a wife, has four children, and then…everyone starts to die.

After his uncle, it’s the three boys with whom he grew up, who drop one by one for various reasons; then a fever comes to town and takes away all of his family but one. And at each funeral, he sees the same man, dressed in black, hovering around the churchyard, giving him significant looks, winks and smiles, but somehow eluding him whenever William tries to engage the man. Finally, at the last funeral, William, desperate to save his daughter Dora, talks to the man, and seems to think they have struck a deal to keep Bellman’s one remaining child alive. From this man (supposedly), Bellman gets the impetus to open a large emporium in London that deals with every aspect of the death industry, from coffins to mourning clothes to stationery to gravestones. It is to be a magnificent edifice, five stories high and boasting its own live-in staff of seamstresses, and Bellman regards the elusive Mr. Black (as William has christened him) as a sleeping partner.

End of part one. Although it’s taken a long time (and a whole lot of details about running the mill) to get there, you’re thinking oh, this is where William Bellman starts interacting with and attempting to placate Mr. Black, who is somehow the nemesis who has brought all these deaths into William Bellman’s life. Hmmm.

End of part one. Although it’s taken a long time (and a whole lot of details about running the mill) to get there, you’re thinking oh, this is where William Bellman starts interacting with and attempting to placate Mr. Black, who is somehow the nemesis who has brought all these deaths into William Bellman’s life. Hmmm.

This is supposed to be a ghost story. There are no ghosts. Bellman is indeed haunted—by his numerous dead, and by Mr. Black—but he manages not to realize it, because he keeps himself so frantic with establishing and running his businesses that he evades every thought in his head not involved with inventories, displays, products, sales figures, and improvements. You keep reading, and waiting. You get more tidbits of information about rooks. You get more descriptions of William’s evasive actions that keep his business thriving but deprive him of all self-knowledge. You finally get to the end, and…what?!

I don’t know what to say about this book. It is beautifully written, and it is obviously about life and death and grief, and yet its main character does not grieve, scarcely acknowledges either the living or the dead, and manages to live in a psychological wasteland of his own contriving. You could call it Victorian gothic, or psychological fiction, or literary fiction, but in the end, it’s 300+ pages of description about the processes, not the thoughts or feelings, of one man’s life. And while I found the technical details of both the milling process from shearing to finished dyed cloth, and even the conception and set-up of the Bellman & Black emporium to be fascinating from an historical perspective, it’s not enough to carry the rest. Bellman is basically running from both death and grief, but it isn’t particularly ominous, or powerful, or poignant, or cathartic. It is lyrical, but it is slow, and its conclusion, for me, was incredibly disappointing and somewhat vague. I can’t say it was a bad book…but I honestly couldn’t recommend it. Which makes me sad.

In my previous review, I mentioned another book with the same feel as this one, in terms of the lyrical narrative and kind of weird premise. The book is Far Far Away, by Tom McNeal. In that story the protagonist, Jeremy Johnson Johnson (his parents both had the same last name) is guided in life by a voice in his head. It is, specifically, the voice of Jacob Grimm, one of the two renowned Brothers Grimm who collected the fairy tales. Jacob watches over Jeremy, protecting him from an unknown dark evil that is being whispered about in the space between this world and the next and apparently threatens him. But when town troublemaker Ginger Boultinghouse takes an interest in Jeremy, a grim (pardon the pun) set of events is put into motion. Many fairy tales don’t have happy endings…

This was such a strange, fanciful, weird, interesting book. Because it’s mostly told from the viewpoint of Jacob Grimm, the narration has an old-fashioned quality that makes you feel like you’re in a fairy tale taking place in the 1800s, but it is in fact set in a 20th-century small town, with electricity, television, and all the amenities. It’s an odd mix, but it works, and the story has an arc with a satisfying ending. I offer it as an alternative.

This was such a strange, fanciful, weird, interesting book. Because it’s mostly told from the viewpoint of Jacob Grimm, the narration has an old-fashioned quality that makes you feel like you’re in a fairy tale taking place in the 1800s, but it is in fact set in a 20th-century small town, with electricity, television, and all the amenities. It’s an odd mix, but it works, and the story has an arc with a satisfying ending. I offer it as an alternative.

Books for Hallowe’en

I went looking for scary reads to feature here, but although I found some things I liked, I struck out when it came to true horror. My selections turned out to be more suitable for the original pagan festival of Samhain, which marks the end of the growing season and honors the dead.

First, because I was in the mood to read something I already knew I liked, I did a re-read of Charlaine Harris’s four-book series about Harper Connelly. Harper has a strange gift, bestowed upon her when she was struck by lightning and lived: She can find dead people, and she can tell you how they died. Traveling with her step-brother Tolliver as her manager, she roves around the country giving the living (and the dead) closure, and getting paid for it. The problem is, although she can see the circumstances surrounding their death, the murderer, if such there be, is never included in the vision.

I don’t know what it is about this series that sets it apart for me, but I enjoy it more than any of Harris’s other series (which I also like). The combination of what Harper Connelly does and how she does it, combined with the poignant story of her hard life and the partnership with her “brother,” Tolliver, just pulls me in.

I hesitated on where to “store” this series on my “shelves” on Goodreads, however, because despite the fact that it contains paranormal activity and is occasionally pretty spooky, the books read more like mystery stories than anything else; once Harper discovers the cause of death, the next natural step is for the relatives and friends of the deceased (and the police) to want to know how, why, and who, if murder is the answer. So I put the series under paranormal AND mystery, and then decided against horror, even though there is some creep factor. Definitely worth a read, however. The four books are Grave Sight, Grave Surprise, An Ice Cold Grave, and Grave Secret.

The next thing I picked up to connect with Hallowe’en was John Searles’s book, Help for the Haunted. The premise for this one sounded intriguing, and at first I thought it would be a good, spooky tale. The set-up of a couple who “helps” haunted souls was interesting, particularly because the author doesn’t go into much initial detail about exactly how they help, so I was left wanting more. The back-and-forth of the story from before to after the couple’s death, all told from the viewpoint of their youngest daughter, Sylvie, was puzzling, and the device of an unreliable narrator (because she was young and naive) and an unreliable secondary character (Sylvie’s volatile sister Rose, whose actions and viewpoints couldn’t be trusted) kept things suspended in “what if?” for quite a while.

When I first started reading it,

When I first started reading it,

I got a feeling not unlike reading We Have Always Lived in the Castle, by Shirley Jackson. Not to say that this anywhere equals the brilliance of that book, but just that you find yourself inside this family with people who seem normal but aren’t, and people who seem crazy but aren’t, and you keep reading because you want to find out what’s true.

Ultimately, this author left important revelations for way too long, spinning out the story with a few seemingly supernatural events here and there to string the reader along, but ultimately I became bored with all the back-and-forth that led nowhere. Once Sylvie determined that she would figure out who killed her parents, no matter what, and sought out such pivotal characters as her uncle, the man who wrote a not-entirely-flattering biography of her parents, and the man she initially suspected of their murder, things finally began to pick up again…only to mean virtually nothing in the face of a completely implausible, albeit surprising, ending.

This book could have been so much more—the characters of Sylvie and Abigail were particularly intriguing, and there were so many ways the author could have chosen to taken it…but he didn’t. I can’t say I liked it, but I can’t condemn it as wholly bad either. A good effort that ultimately disappointed. And I couldn’t even shelve it in “horror.” More gothic and paranormal than anything, with a small modicum of suspense.

My final choice was Diane Setterfield’s book, Bellman & Black. This book has been on my “to read” list for awhile; I had previously read and greatly enjoyed The Thirteenth Tale by this author, and knew that even if this wasn’t the ultimate in horror, it would at least be intelligent, well written and well plotted. The jacket copy telling us “rooks never forget” sounded ominously Edgar Allan Poe-ish…

My final choice was Diane Setterfield’s book, Bellman & Black. This book has been on my “to read” list for awhile; I had previously read and greatly enjoyed The Thirteenth Tale by this author, and knew that even if this wasn’t the ultimate in horror, it would at least be intelligent, well written and well plotted. The jacket copy telling us “rooks never forget” sounded ominously Edgar Allan Poe-ish…

I am loving this book…but you couldn’t account it as horror by any stretch (at least not so far), although parts are foreboding, haunting, and mysterious. It has the same old-fashioned fairy-tale-retelling feel as a strange and fanciful book by Tom McNeal called Far, Far Away that I read a few years back with my high school book club.

Because I took so many days to read Help for the Haunted, I wasn’t able to finish Bellman & Black in time to review it for today’s post, so that will wait for a day or two—I still have about half the book to go.

But I feel pretty confident that Setterfield will not disappoint, and that it’s sufficiently ghost-filled to make for satisfying reading on All Hallows Eve.

In the spirit of the holiday and the theme of Bellman & Black, here are a pair of rooks, styled after Odin’s corvids Huginn and Muninn. Happy Hallowe’en, and Blessed Samhain to you!

Reading culture

I thought I would “publish” the remarks I made for a panel with Antioch University Library Director Lisa Lepore and Adult Services Librarian (LAPL) Eugene Owens at the California State Library Convention on Friday. Our topic was “Creating a Reading Culture in Libraries.” My part was about public libraries.

When I was a teen librarian, to get kids reading we started a program one summer called Book Café. We set up round tables that seated eight; we served cappuccino and cookies; and we introduced the idea of book-talking. We asked the teens to bring whatever they were reading, and to sit at a table labeled with their favorite genre—fantasy, mystery, or whatever. Our idea was that they would go around the table, each book-talking the book they had brought, and then maybe trade books at the end if someone else’s sounded appealing.

After we did a demo of a book talk from the front of the room and told them to get on with it, a sixth-grader named Harrison came up to me and the other teen librarian.

“Listen,” he said. “I just read a book that was so good, I KNOW that if they heard about it, everyone in this room would want to read it. Can I share it from the front of the room?”

We gave him the microphone. He book-talked his book, everyone applauded, and he sat down. Several hands went in the air. “Yes?” I asked. “I have one I want to do too!” another kid said. So I motioned her up to the front and handed her the mic, and for the next two hours, the mic was handed off from one to the next for about 24 teens. It had become like Open Mic Night but with books.

After this, Book Café became our most popular program. Teens would stop us in the library to request more sessions. Teens would ask other teens, Are you coming? You’ll like it! Attendance for the program climbed from the 30s into the 60s. And the teens clamored to select a book from our stash of teen fiction as prizes for summer reading club drawings.

We had created a culture of reading.

In the 1990s, when online search engines and databases began to accumulate and hold the knowledge formerly accessible mainly in books, librarians had to meet the challenge of information-seeking in a different arena. They had to learn, and they had to teach, adapting to new technologies and formats. Many librarians succumbed to panic. Their relevance was challenged with the familiar phrase, “Why do we need the library when we have Google?” The frantic and continually changing evolution of the library had begun. Books felt less relevant. For decades now, librarians have been like sharks, constantly moving into some next phase of justifying their existence. But a friend of mine, a professor in the UCLA MLIS program, said recently, “Libraries have Shakespeare, we have Toni Morrison, we have all the riches of literature—why are we running from that? We are the keepers of the books, and if it’s education that we want to promote, how better than to do so by creating a culture of reading for our children? Why do we not trust reading, and trust ourselves not only as its collectors but as its purveyors?”

“Certainly we get essential information from factual books, but it is experience we need most. If we would live richly, we can expand our lives more by sailing down the Nile with Cleopatra, looking at the cherry trees with Housman, or sweating it out to triumph at long last with Moss Hart than we can by gathering all available information on Egypt, raising cherries, or writing for the theater.”

—Margaret A. Edwards,

The Fair Garden and the Swarm of Beasts (1969)

In 1932, Margaret A. Edwards, the first teen librarian, said essentially the same thing to her colleagues, who were holding fast to the information standard and shunning the idea of devoting their education as a librarian to learning about and giving people books they would enjoy reading. I propose that the same thing is still true 87 long years later, and it’s past time for us to wake up.

In marketing pamphlets and in some online promotions, this year’s summer reading program has for the first time been changed to a summer “learning” program. Children’s librarians are being encouraged to do educational programming. The iREAD theme for 2020 is “Dig Deeper,” and its promotional language no longer encourages reading for the simple—and profound—pleasure of reading. It seems that everything must tie back to STEM.

The CSLP theme for 2020 is “Imagine Your Story.” This sounds more promising until you read the slugs underneath each age group: Building reading and language skills. Motivating teens. Preparing children for success. This is the language of business. Success to me is the kid who’s reading three grades above his age level because he loves books.

CSLP has published an impressive white paper on their website in which they review all the studies made of students and summer learning loss, and the advantages of participating in a program to combat that loss. One of the things they note is that public libraries face increasing accountability standards and scarce funding, and therefore must resort to evaluation of their programs. But this clinical review of best practices leaves the heart and soul out of the reason for cultivating reading in children and teens: to promote a love of reading that will be of lifelong benefit and advantage. If we persist in equating libraries with school, and take the pleasure component out of reading, we will lose those children.

Dr. Stephen Krashen, the leading expert on the subject of free voluntary reading, reminds us: People who read because they want to, with no assignment components—no book reports, no questions, no tests, no analysis—do better in school by far than those who don’t read or who only read under compulsion. Krashen’s premise, which has been broadly verified, is that the source of a wide vocabulary, good grammar, spelling skills, and competent writing ability is free voluntary reading. He goes on to note that students who participate in sustained silent reading programs go on to read more on their own than those

who do not.

By contrast with the curriculum-based initiative to push school children into reading with education and information as an end, some progressive library systems are taking note that a return to our roots—to the philosophical underpinnings of library culture—might actually be the most modern and up-to-date course we could pursue as librarians. The Sacramento Public Library has recently created an initiative for its entire staff, one in which that staff is expected to place reading and readers’ advisory at the top of their list of job priorities as they create a culture in which literature is as important as information and technology, and readers are valued.

Sacramento PL took an in-depth and global approach to this goal. First, they created the culture within their system by involving their entire library staff.

- They incorporated books into library meetings as icebreakers;

- They sent out weekly emails asking what “you” are reading, and actually expected an answer;

- They encouraged reading through staff challenges;

- They provided time during the workday for reading;

- They incorporated reading into job performance evaluations;

- And they provided formal readers’ advisory training.

Then they expanded to consider the library itself:

- Reading displays and staff picks were created for every section of every branch, and staff were assigned to maintain them;

- Books became central on all fronts, using merchandising standards;

- They made sure that everything from library events and programming to social media posts reflected their new initiative.

Finally, they started taking the initiative outside the library with outreach events.

- They hosted a readers’ advisory table at the state fair;

- They did a Chamber of Commerce mixer with stacks of ARCs on each table as décor, so people could take books home with them to keep.

Their new unofficial motto became “books are the hook that get people in the door,” and everything reflected this.

In other key places across the country, this is also beginning to happen. Libraries in Colorado and in Chicago have readers’ advisory interest groups or committees, and belong to such global initiatives as the Panorama Project, a coalition of readers’ advisory professionals who offer support for librarian networking and training and are also involved in ongoing research on the impacts of such activities as community reading events.

As librarians, we cannot afford to view our entire function as transactional. Our intellectual lives are important and should be valued. Public libraries, unlike academic settings, have not traditionally promoted time for librarians to take in reading and to produce new knowledge, but this needs to change, especially in an educational climate that has eliminated school libraries and teaches to the exam. As a public librarian for 11 years, I know what we are up against, besieged by both small tasks and large social concerns, until our work-day is so fragmented that we are in danger of losing focus. But I am asking you to make reading your priority, for the simple reason that no one else is doing or will do it.

No matter what other services you offer, when you observe your work space you realize that you are sitting in the center of a great big box full of books. And although librarians religiously keep up with their collection development, buying the worthy and the popular each year and expanding their collections, we need to acknowledge that sometimes we forget it’s our job not just to maintain our collections but to have deep knowledge of them and know how to present them to our patrons.

Let me share some statistics with you:

- According to a 2017 Pew Research survey, 64 to 73 percent of patrons say they come to the library to find a good book.

- For a 2016 Materials Survey for Library Journal, Barbara Hoffert discovered that FICTION accounts for 65 percent of print circulation and 79 percent of e-book circulation in libraries.

- In 2015, NoveList conducted a “secret shopper” survey. The main question was, “If the book the patron was seeking was not in the library, did the librarian then suggest an alternate title?” 75 percent of patrons answered NO.

In the face of these figures, are we not derelict in our duty as librarians if we fail to create opportunities around books? What better way could we serve our public than to realize that reading and advising are a skill set, to enable ourselves to be readers, and to advise our community that we are not only able but eager to connect them with the books they want?

The sad truth is that most library patrons don’t even know this is a service we offer. If people don’t know what we have and we don’t tell them, we are and will remain invisible. When we choose to adopt philosophies imposed upon us by schools, by business, by those who don’t understand what a library can be and what librarians can do, we weaken our impact.

I would like to challenge you to take these ideas back to your home libraries, to consider the benefits of a community rooted in a love of reading, and to share your knowledge and expertise with them by creating a pervasive reading culture in your community. I believe the benefits of truly “making story our brand” will be immeasurable.

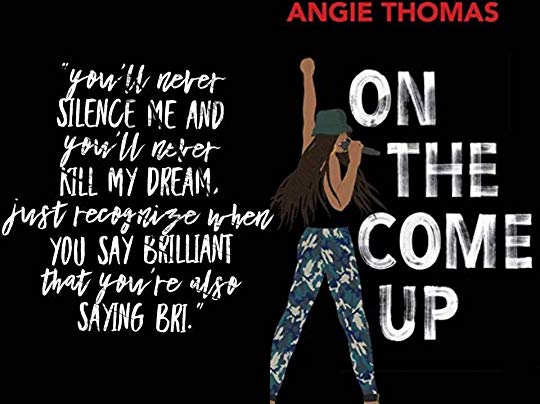

On the Come Up

You always worry when the first book of a new author is as good and as much of a hit as was The Hate U Give (THUG), by Angie Thomas—sales, prizes, a movie, all for a first novel. You worry that she’ll be a one-hit-wonder, that the kudos for the first book will freeze her in her tracks, that she’ll never be able to up her game. But this book was definitely “on the come up.”

Having read both, I feel like maybe this one more directly expresses the personality and background of its author, that perhaps it was a project closer to her heart and to her authentic self.

THUG was about a girl who was being victimized by the system and figures out that speaking her mind and finding her voice are important. It’s about the giant and overwhelming exterior forces that shape a person, and what it means to go up against them.

On the Come Up is the story of quite a different girl, one whose story is driven by the choices she makes while pursuing her dream. Although the books share some commonalities (project kids going to school in the privileged white world, conflicts between the traditions of home vs. the expectations of outsiders), this book is more intimate, with a tight narrative focused on protagonist Bri.

Bri Jackson lives with her mother, Jay, and her older brother, Trey. Her father, a rapper, was shot by a gang member when Bri was little; her mother, eight years clean after a drug addiction, is doing her best to provide for the family, working as a secretary at their church. Trey, who graduated from college summa cum laude, can’t find a “real” job and is working in a pizza parlor to help make ends meet until he can figure out a way to continue his schooling (he wants to be a doctor), but sometimes, when trying to stretch the dollars, it’s a choice between rent, food, or lights. Then Bri’s mom loses her job, and the desperation accelerates.

Bri is a talented rapper who wants to follow in her father’s footsteps, but using her own words and style. She is well motivated by a desire to take care of her family, but she’s also 16 years old, so she is impulsive, stubborn, and occasionally irrational as she acts out against the injustices in her life. She is also determined on getting what she wants, for her, for fame and security, for love. She is pushed and pulled by people who want to help her and those who merely want to profit by her talent, and she hasn’t yet figured out that if she’s not true to herself, none of it will work.

The incorporation of Bri’s lyrics give the story authenticity and depth. Writing prose and writing poetry (or lyrics) are such different skill-sets that it’s always impressive when an author manages both in the same work, and makes them work. Thomas is a gifted writer, and her exploration of the themes of systemic racism and inequality, social injustice, and gang violence are only exceeded by her skills at depicting them through utterly believable characters and a compelling story line. I’m impressed with book #2, and can’t wait to see what she’ll be up to next.

Here is the author herself, delivering some of Bri’s lines in the rapper “ring”:

READERS’ ADVISORY NOTES: Thomas’s books would obviously appeal to anyone looking for diversity in their reading material. But just as the so-called “problem novels” of the 1970s and ’80s fell by the wayside because they were too one-track, diversity can never be the only reason for a book to be judged “good.” Angie Thomas writes powerful stories of coming of age in an atmosphere of adversity. They are artfully written, character-driven, and satisfying. Most young adult readers who enjoy realistic fiction and like a scrappy, determined protagonist would appreciate and enjoy On the Come Up. The evocation of empathy with the targets of racial profiling is a big plus to a good story.

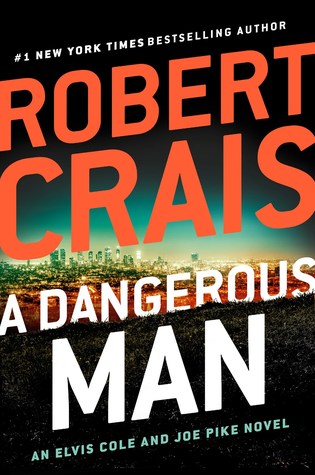

The Man

Twice in two weeks I was able to read the latest in a mystery series I have followed from the beginning. What a treat!

Robert Crais has been writing the saga of Hawaiian shirt-wearing Private Investigator Elvis Cole and his sidekick, the inimitable Joe Pike of granite mien and special (forces) skills, for 18 books now, occasionally interspersing them with a stand-alone thriller here and there. Although I have mostly preferred the stand-alones to the series, I never miss any of Crais’s books, because he tells a good story and because I like that they are set in Los Angeles.

There’s no denying that this series, like any other long-running one based on the same people in the same city, has had its ups and downs. There have been books I couldn’t put down for 48 hours straight, and others I could barely make it through. I liked A Dangerous Man for the very reason that a few other people cited for disliking it—it was straightforward. There have been a few of these that got so complex and brought in so many extraneous people and details that it spoiled the lead, which for me is always the partnership between Elvis Cole and Joe Pike, and how they have developed such synchronicity.

There’s no denying that this series, like any other long-running one based on the same people in the same city, has had its ups and downs. There have been books I couldn’t put down for 48 hours straight, and others I could barely make it through. I liked A Dangerous Man for the very reason that a few other people cited for disliking it—it was straightforward. There have been a few of these that got so complex and brought in so many extraneous people and details that it spoiled the lead, which for me is always the partnership between Elvis Cole and Joe Pike, and how they have developed such synchronicity.

The initial encounter in this one was, as I said, simple—nobody calling the office with a long and complex tale to be sorted. Joe Pike goes to the bank, and Isabelle (Izzy) Roland is the teller who waits on him. Her boss asks her to take an early lunch, so she leaves the bank only minutes after Joe, who is still on the street by his car. A couple of guys in an SUV pull over next to her on the curb; one gets out and engages her in conversation, and before she knows it, she’s being forced into the car and abducted. Joe spots the look of panic on her face, and does what Joe does—he follows, he outwits, and he rescues, wreaking a little havoc on the kidnappers in the process and then turning them over to the police.

From this point on, it does grow a little more complicated, because the power behind the kidnappers redoubles efforts to get hold of Isabelle. When she calls Joe in a panic because SUVs have been trolling her street and then disappears, Joe appoints himself her bodyguard and avenging angel, but at this point also decides it’s time to pull in both John Chen (medical examiner) to run some fingerprints, and friend Elvis to use his P.I. contacts and figure out why these people are so determined to get control of a 22-year-old bank teller with an old car, a falling-down house, and no apparent reason to be of interest to anyone in particular.

It’s a believable story, well told, and holds your interest start to finish. The question I was left with was, is “the dangerous man” of the title the person who is relentless in his pursuit of Izzy? or is it Pike himself? In a showdown, I know who I would pick.

READERS’ ADVISORY NOTES: This is a series you could suggest to a mystery lover who is a fan of Michael Connelly, the other guy who writes a series (Bosch) based in Los Angeles. Although Harry Bosch is a policeman and Elvis and Joe are private/independent, they share the characteristics of being mavericks who take direction from no one and who are relentlessly determined in pursuing their objectives. Because of the locale, the scene-setting is quite similar, and I have always wished the two authors would get their characters (neighbors in the Hollywood Hills) to meet up and collaborate! Also, either series might appeal to people who like noir fiction, as all of these detectives tend to be involved with the darker elements of their trade, and sometimes the books feel like an offshoot of 1940s Hollywood, a lá Walter Mosley or Duane Swierczynski.

A feast

The mail brought me a delightful surprise this past week: Deborah Crombie’s latest in her Kincaid/Duncan mystery series. (I had forgotten that I had excitedly pre-ordered it a few months back.) It’s one of the British police procedural series that I follow religiously, but patience is required for this one, because Crombie is not a speedy writer. This is #18 in the series, and #17 was published in February of 2017, so it’s been a long 31 months in between.

In A Bitter Feast, Scotland Yard Detective Superintendent Duncan Kincaid and his wife, Detective Inspector Gemma James, have been invited for a relaxing weekend in the Cotswolds countryside at Beck House, as guests of the family of Melody Talbot, Gemma’s detective sergeant. The Talbots are wealthy and somewhat notorious as the publishers of one of Britain’s major newspapers, and except for Duncan and Gemma and her friend Doug, Melody has been completely silent about the family connection so as not to influence her co-workers (for good or ill) due to her prominent family connections.

In A Bitter Feast, Scotland Yard Detective Superintendent Duncan Kincaid and his wife, Detective Inspector Gemma James, have been invited for a relaxing weekend in the Cotswolds countryside at Beck House, as guests of the family of Melody Talbot, Gemma’s detective sergeant. The Talbots are wealthy and somewhat notorious as the publishers of one of Britain’s major newspapers, and except for Duncan and Gemma and her friend Doug, Melody has been completely silent about the family connection so as not to influence her co-workers (for good or ill) due to her prominent family connections.

The weekend for which they have been invited is to feature a charity luncheon hosted at the Talbots’ home and catered by chef Viv Holland, whose current position as co-owner of a local pub doesn’t reflect her illustrious background as a Michelin chef. Lady Addie Talbot, always mindful of her own influence and desirous of helping her friends and protégés, sees this luncheon as an opportunity to increase the usually self-effacing Viv’s fame, and accordingly invites national food bloggers and restaurant critics; but this action sets some unexpected events into motion that will scar the day with tragedy and provoke additional crimes to cover someone’s tracks.

This was a somewhat subdued book in the series. That’s not to say it wasn’t thoroughly enjoyable, but it was a bit different in that Duncan and Gemma weren’t the principal cops on the case. You just knew, when the book opened with the prospect of an idyllic country weekend away for the entire Kincaid/James clan, that it was too good to be true, and sure enough a car accident puts Kincaid out of the picture before he can even arrive at the Talbot estate. When the investigation of the two people in the car that hit him turns up a finding of suspicious death, Gemma and Duncan both become involved in the solution of this and another, later crime; but because it’s not their turf, the lead is taken by a local inspector, and they are demoted to the role of helpers. Additionally, because of Duncan’s injuries he’s not his usual competent and capable self, distinctly shaken by the accident and its aftermath.

The mystery is a good one; I enjoyed the past-and-present details of the life of Chef Viv Holland, including all the delectable descriptions of the food she was producing, the cast of characters inhabiting her restaurants (Ibby, Jack, Antonia, Bea, and the charismatic but volatile Irishman, Fergus O’Reilly), and the complications of her personal life. Likewise, the disclosures about Melody Talbot’s parents, Ivan and Lady Addie, the picturing of their beautiful home with its Gertrude Jekyll-inspired gardens, and the sleepy autumnal setting of the golden Cotswolds is compelling and lends additional charm.

One thing that put me off a little: The book became particularly busy, with too much back-and-forth trading off of cars, duties, and childcare, because of the presence of the entire family. Although son Kit plays a somewhat pivotal role in this book, the constant need for Gemma or Duncan to find someone to watch Toby and Charlotte so they could go off and solve crimes added a lot of unnecessary detail, as did all the descriptions of places and activities pursued specifically to entertain the children, from zoos to ice creams to croquet. The story might have been less cluttered if the kids had all gone to the grandparents for the weekend, leaving Gemma and Duncan to enjoy their holiday unfettered and (later) to pursue their sleuthing. Of course, life is messy and cluttered and busy, so perhaps I am just reacting from the perspective of a single person without too much patience for this kind of thing!

Although this is not my favorite of Crombie’s series, it certainly stands up as a worthy participant, and is well worth the time. I just wish she were a faster writer; it’s a long time between books, and I miss Duncan and Gemma while they’re gone!

Upper Slaughter, The Cotswolds

READERS’ ADVISORY NOTES: This is a great series for dedicated mystery readers whose preference is for detectives with whom they can become familiar and develop continuity and relationship. Both the personal and professional lives of these two are intriguing, and even more so for being lived together. Crombie’s usual habit (not seen in this one) of alternating the lead in each book between Kincaid and James keeps the series fresh. The mysteries are usually satisfyingly complex and mystifying, and maintain attention throughout. And for those whose preference is specifically the British mystery, you can’t beat Crombie, her surprising nationality as a Texan notwithstanding.

Heist

I haven’t read a book by John Grisham for many years, and my reading was mostly restricted to his legal thrillers (not being a fan of baseball, his other main focus), which I enjoyed quite a lot, particularly A Time to Kill and Runaway Jury. Honestly, when it comes to those kinds of books, he is as much of a screenwriter as a novelist, because they are so aptly suited for the visual medium. I have enjoyed both reading and watching them.

In recent years, it seems like he has been trying to expand his repertoire (or soften his image?) to include other kinds of fiction—A Painted House, Playing for Pizza, Skipping Christmas, and this one I just finished, Camino Island. I’m not sure that these efforts have been entirely successful; while these books have all been pleasant, interesting, and well written, they don’t seem to me to have the snap of his legal dramas.

In recent years, it seems like he has been trying to expand his repertoire (or soften his image?) to include other kinds of fiction—A Painted House, Playing for Pizza, Skipping Christmas, and this one I just finished, Camino Island. I’m not sure that these efforts have been entirely successful; while these books have all been pleasant, interesting, and well written, they don’t seem to me to have the snap of his legal dramas.

This book is billed as a “heist” novel, but although the theft of five original manuscripts written by F. Scott Fitzgerald from Princeton University is detailed in the first part of the book, there isn’t much excitement surrounding it. The heist planning was interesting, but because it was all done undercover, so to speak, with distraction rather than direct action enabling the crew to pull it off, it wasn’t all that gripping.

Then there are not one but two abrupt shifts in the book—one to a bookstore owner and his history as a bookseller, and the other to a broke, blocked writer trying to figure out how she’s going to survive. These are initially confusing, until you realize that both these people are going to have some role in the further history of the heist.

Bruce Cable has a bookstore on Camino Island, in Florida, and the tracing of certain industry connections of his has led the insurance company to conclude that he may know something about the missing manuscripts that the company will be expected to pay out on if they aren’t located and returned to Princeton. The company hires an unnamed investigative entity who in turn hires Mercer Mann, a writer who had some success with her first novel, but is now blocked on her second and has just been let go from her teaching job. Mercer has ties to the island (her grandmother lived there and she visited every summer as a child), so the investigators feel it will seem natural for her to “infiltrate” by staying at her grandmother’s cottage, ostensibly to write, and inserting herself into the local literary scene at the bookstore. They hope that by doing so, she can discover whether there is any truth to the rumors about the manuscripts being linked to Bruce Cable.

I most enjoyed the evolution of the bookstore, with all the details involved; I hadn’t picked up this book specifically because it was about books and reading, but luck took me there, and I always like to hear about the set-up, philosophy, and day-to-day business practices of bookstores and their owners.

I least enjoyed the character Mercer (the young woman writer), who whined a lot about not being able to write but didn’t actually seem to be trying that hard amidst all her other distractions.

A little excitement comes back into the book when the FBI and the insurance company catch some of the thieves and it seems that Mercer’s rather flat-footed undercover work with Bruce Cable may actually lead to one or more of the stolen manuscripts being located. But the ending itself was rather a sterile wrap-up. I suppose everything was resolved adequately, but again, not particularly excitingly.

It was a pleasant read, but not a gripping one, and definitely not my favorite of Grisham’s.

I was somewhat embarrassed to discover that while I’ve been ignoring his recent adult works, I also apparently missed that he’s been writing a series for young teens about a 13-year-old lawyer, Theodore Boone. These sound like books I could promote to reluctant young male readers; I’ll have to read one and see!

Although The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek is, indeed, about one of the WPA Pack Horse librarians, the focus of that book is almost entirely on a singular character, a coal miner’s daughter, Cussy Mary Carter. Cussy (or Bluet, as she is more commonly known to the people in her neighborhood) is one of the last of the blue-skinned people of Kentucky, a group that suffered from a rare genetic anomaly that caused their skin to carry a pale blue tint that darkened, with a blush, to the shade of a blueberry. Because of her skin color, she is feared or hated by a large percentage of the population of her rural Kentucky settlement, treated even worse than the regular “colored” people, and this proves to be a danger as she goes about her work as a Pack Librarian. But it also allows her a little hope, as the people who are grateful for her efforts to bring them books and reading begin to be open to the idea that she is no different from them despite her peculiar shade.

Although The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek is, indeed, about one of the WPA Pack Horse librarians, the focus of that book is almost entirely on a singular character, a coal miner’s daughter, Cussy Mary Carter. Cussy (or Bluet, as she is more commonly known to the people in her neighborhood) is one of the last of the blue-skinned people of Kentucky, a group that suffered from a rare genetic anomaly that caused their skin to carry a pale blue tint that darkened, with a blush, to the shade of a blueberry. Because of her skin color, she is feared or hated by a large percentage of the population of her rural Kentucky settlement, treated even worse than the regular “colored” people, and this proves to be a danger as she goes about her work as a Pack Librarian. But it also allows her a little hope, as the people who are grateful for her efforts to bring them books and reading begin to be open to the idea that she is no different from them despite her peculiar shade. The other protagonist is Margery,

The other protagonist is Margery,