Spooky reads for October

There are a lot of requests on Facebook reading pages for haunted tomes to make their month more enjoyable (and more chilling). So I decided to comb through my “horror” and “paranormal” categories on Goodreads to see if I could find some good reads to recommend. I am not much of a horror aficionado, so those are in short supply, but I do like a good ghost story. Here’s a list of a few I have enjoyed, both new and classic, with some young adult stuff thrown in because it is also entertaining for we grownups.

The Haunting of Hill House, and We Have Always Lived in the Castle, by Shirley Jackson. Very different vibes in these two, but I can say that they are both truly creepy. Don’t judge the first by its movie(s), it’s so much more nuanced and weird than anything Hollywood managed to put onscreen.

Starling House, by Alix E. Harrow. Southern gothic horror. Here is my review.

Vampire books by Anne Rice (the first two are the best). Classic paranormal. I also liked Sunshine, by Robin McKinley, a completely different take. And if you like sex and diners with your vamps, there is, of course, the “Sookie Stackhouse” series by Charlaine Harris.

The Harper Connelly books, also by Charlaine Harris, recently reread and commented on by me here. You could also try the “Midnight, Texas” series, though they are not my faves apart from my love for their protagonist.

The Graveminder, by Melissa Marr. “Sleep well, and stay where I put you!”

The Library of the Dead, by T. L. Huchu. Ghosts with a Zimbabwean twist. I reviewed this one too.

A Certain Slant of Light, by Laura Whitcomb. A dreamy, unusual ghost story. There is a sequel I haven’t read, called Under the Light.

Hold Me Closer, Necromancer, by Lish McBride, a somewhat comedic take on a modern necromancer and his paranormal pals. Big fun. There is a sequel called Necromancing the Stone.

The “Visions” series by Lisa McMann.

Also, please enjoy the following excellent ghostly tales, which I reviewed here for a previous Hallowe’en post:

Meet Me at the River, by Nina de Gramont

The “Lockwood & Co.” series, by Jonathan Stroud.

The “Shades of London” series, by Maureen Johnson.

…and a few more.

Reiteration

I got frustrated this week by my seeming inability to pick a winner of a book, and fell back on a sure thing by rereading Charlaine Harris’s four-book series about Harper Connelly, victim of a lightning strike, who uses the ability given her by this event to make a new life for herself. And now, once again stymied by a new-to-me book series that isn’t grabbing my attention or enthusiasm, I’ve been considering rereading Harris’s other series about dystopian gunslinger Lizbeth “Gunnie” Rose. So imagine my delight, after going to Goodreads to remind myself which book was first in the trilogy, at discovering that Harris wrote two more in this series while I wasn’t paying attention!

If you’d like a more thorough dissection of these two favorite series of mine by Harris, go here and read all about them. This post reviews the third book in the Gunnie Rose series. And stay tuned for reviews of The Serpent in Heaven, and All the Dead Shall Weep.

Hiatus, nostalgia, TV

I haven’t published anything here for a while because I started reading Demon Copperhead, the new book from fave author Barbara Kingsolver, and it has been taking forever. I am enjoying the voice of the protagonist and the high quality of her descriptive writing and somewhat quirky scene-setting, but the combination of the length of the book and the depressing quality of the narrative finally got to me at about 83 percent, and I set it aside to take a quick refreshment break.

I re-read two books by Jenny Colgan—Meet Me at the Cupcake Café, and The Loveliest Chocolate Shop in Paris—for their winning combination of positivity, romance, and recipes, and enjoyed them both. My plan was to go back to Kingsolver today, but instead I found myself picking up Dying Fall, the latest Bill Slider mystery by Cynthia Harrod-Eagles, which has been in my pile for months. I will get back to Demon Copperhead at some point, but the mood isn’t yet right.

Meanwhile, Netflix made me happy this weekend, having come out with season one of Lockwood & Co., adapted, partially written, and directed by Joe Cornish, and based on the young adult paranormal mystery series by author Jonathan Stroud. This has been a favorite series of mine since I read book #1 with my middle school book club and eagerly perused all the rest as they emerged from his brain onto the page (there are five books and a short story in it).

The series is set in a parallel world where Britain has been ruled for 50 years by “the Problem”—evil ghosts that roam freely, but can only be dealt with by children and teenagers young enough to be in touch with their perceptive gifts. Adults can be harmed by them but can’t see or even sense them, while the youth still see, hear, and sense their presence and fight them by discovering their “source” (the place or object to which they are attached) and either securing or destroying it.

The mythology seems to have evolved at least partially from faerie, vampire, and werewolf lore: The main weapons are iron chains, silver containers, running water, salt bombs, lavender, and longswords! The ghost-hunting teens are most of them employees operating under the supervision of corporate, adult-run agencies, but Lockwood & Co. is independent of adult supervision. It’s a startup existing on the fringes, run by two teenage boys—Anthony Lockwood, the putative boss and mastermind, skilled sword fighter and ingenious planner, and George Karim, the brainy researcher who provides background for their cases from the city’s archives. The two have advertised for and just recently acquired a girl colleague, Lucy Carlyle, who is new to London and technically unlicensed, but more psychically gifted than anyone they have ever met. This renegade trio is determined not just to operate on their own but to outdo the agency blokes in all their endeavors, so they take risks no adult at the corporations (or at DEPRAC, the Department of Psychical Research and Control) would sanction, in order to gain both notoriety and clients.

Cornish and his colleagues have nicely captured both the flavor of the overwrought atmosphere of beleaguered London and the perilous camaraderie of the principal characters—Lockwood, George, and Lucy—in their series. Season one covers the events from books #1 (The Screaming Staircase) and #2 (The Whispering Skull), so one assumes there will be at least one and perhaps two more seasons, if viewers make it popular enough for renewal. I certainly hope they do! But in case that doesn’t happen (or even if it does), the books are out there, and well worth your attention (and I don’t just mean middle-schoolers!).

Verisimilitude

I love that word, and it’s not one that you often get the chance to use. But it perfectly describes the book Holding Smoke, by Elle Cosimano, which I reread this week after a six-year hiatus and discovered that I liked it every bit as well the second time as I did on first perusal (another good word).

I originally picked up the book back in 2016 because of its setting—juvenile hall. While I was in library school, I took a class that required racking up service hours as part of the grade, and a dozen of us started book-talking groups (like a book club, but each person reads their own choice of book) in seven of the living units there. My friend Lisa and I ran a group in one of the four maximum security units (which more closely resembled the set-up of this book), and we loved doing it so much that we ended up continuing for two years, long after both the class and library school were over.

Cosimano, whose father was a warden, really has the setting, the interpersonal relations and interactions, and the rhythms of the place down in this book. I felt like I was right back at Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Detention Facility in Unit W, but with a new group of troubled kids.

The title of this blog post doesn’t entirely fit the vibe of the book, since part of the story qualifies as magical realism. The main character, John Conlan, nicknamed Smoke, is serving time in a long-term facility in Denver, Colorado, for two murders, and although one was self defense and the other was committed by someone else, no one believed any part of his account when it went up against the damning circumstantial evidence. During the course of the event, John died for a period of six minutes and then was brought back, and during that six minutes had an out-of-body experience that he discovers he is now able to replicate. So while the other inmates are locked up inside the concrete walls of the “Y,” John is able to pass through them and wander out in the world in spirit form, tied to his body by a sort of cable that seems to be fraying the more trips he takes.

He uses this ability to good purpose by checking in on the families or business partners or girlfriends of other inmates and reporting back on their status—are they okay? are they cheating me? are they cheating ON me? No one can figure out how Smoke is communicating with his outside sources to garner this information, but they’re willing to pay in favors for his services.

He doesn’t use this ability in his own interests until, in the course of observing a drug dealer’s transactions at a bar, he meets a waitress he calls Pink, who can see and hear him in his spirit form, and with her help he begins to explore the truth around who could have manipulated the situation to put him in prison. But someone has a vested interest in keeping him there and keeping him quiet, and suddenly his existence is perilous, as is everyone’s who helps him…

The scene-setting, the characters, the pacing of this story are all visceral and gripping, and I also appreciated the philosophical elements Cosimano brings to the characters. I had no trouble with the suspension of disbelief over Smoke’s abilities, and the author makes the whole thing palpable by setting up and exploring the rules of how those abilities work. There are quite a few twists, and an exciting ending I didn’t see coming. This is a good example of gritty fiction crossed with the paranormal that will appeal to a wide range of teen readers. Although I have enjoyed Cosimano’s other books (particularly the Finlay Donovan series), I think I would call Holding Smoke her best so far.

Ash (aka Cinders)

Back in 2012, I read Malinda Lo‘s science fiction book, Adaptation, and gave it a four-star rating and a good review. It was good storytelling, had romance both gay and straight, and hey, aliens!

Ever since then, I have meant to go back to her and at least read Ash, her Cinderella retelling with a sapphic twist, and this week I finally did so, as part of my preparation for my “speculative fiction” unit at UCLA for my Young Adult Literature class.

I have to say I was underwhelmed. There are nice things to say about the book: The writing is sometimes lyrical, and the scene-setting imagery (descriptions of forests, countryside, hunting on horseback, etc.) is lovely. Some of the characters are attractive, at least in their physical descriptions. But it seemed like Lo didn’t quite know how to both present/exploit the original fairy tale and then deviate from it effectively (or provocatively, as most readers would be expecting).

The details of the original that were retained were clichéd, with the stepmother being almost a cartoon caricature and the daughters’ personalities left unformed beyond the usual, which is to say, the elder is egocentric, frivolous, and mean, while the younger (less attractive and therefore less valuable?) retains a smidgen of humanity. The father likewise becomes the bum who didn’t pay the bills and left everyone in the lurch. And the prince (central to the original tale) has barely a cameo appearance in this book. The character of Aisling’s absent (dead) mother was so much more fully formed than most of the people in this story who were alive—it was both disconcerting and not ultimately useful.

You would think, against this backdrop, that the main players—Aisling or “Ash” (Cinderella), the King’s Huntress, Kasia, and the mysterious Fae suitor, Sidhean, would shine. They don’t, and nor do their relationships. Although Ash regards Sidhean with awe and wonder and looks forward to his visits and his company, there is little emotional involvement visible from either side (except for one or two extremely brief repressed moments on Sidhean’s part), and the prospect of going away with him does not fill Ash with joy, despite her miserable lifestyle from which one would think she would be desperate to escape.

Likewise, the meetings with the Huntress only hint tentatively and subtly at there being any kind of fascination (on either side), let alone attraction, and are so quietly and decorously handled that you keep wondering if you imagined reading the synopsis of the book in which these two supposedly fall in love. There are moments…but they remain unarticulated until almost the very end, and there is little sense of who the Huntress is, with few glimpses into her past and present and almost no indication of her feelings. There is no love story here, except in the vague dim recesses of the two characters’ minds—no verbalization, no wooing, no physical manifestation.

In effect, this book has an almost totally flat affect. Although there are conflicts (as Ash learns from her rather obsessive reading of fairy tales, it’s a big deal to go away with a fae into his land, where time moves differently and people can become trapped forever), they are not ultimately dealt with as if they are that significant. I don’t want to be a spoiler here, but the resolution with Sidhean was puzzling, abrupt, and unsatisfying.

In this setting/world it also seems that a relationship with a fae prince is so much more scandalous than is a lesbian one—which seems almost completely taken for granted—that the reader is denied even the frisson of forbidden love, and when the two women eventually get together, it verges on mundane. And I mean, we all say we want books in which same-sex relationships are accepted and taken for granted, but…this is a fairy tale retelling in which “Ash” supposedly ends up a princess, married to a prince, so…shouldn’t there be some kind of fireworks when that doesn’t happen?

I was just puzzled by this book—especially all the ways the author chose not to go. It’s not exactly a pan—it’s a pleasant enough read, and has some interesting moments—but it was so much less than I hoped or expected.

Akata Witch

My UCLA class of masters students who are studying Young Adult Literature with me this quarter are a sharp bunch, and I have been thoroughly enjoying both discussing the books we are reading for class, and reading their synopses and review comments on Goodreads, where they post their conclusions for class credit.

One recent option for our unit on the paranormal was Akata Witch (The Nsibidi Scripts #1 of 3), by Nnedi Okorafor, and since it was the only assigned work I had not yet read, I picked it up last week along with a number of my students. I wasn’t sure I was going to enjoy it; I read Okorafor’s book Who Fears Death and had a decidedly mixed reaction, partly admiration for its ambition, partly frustration for its all-over-the-map plot that felt like it never settled to one coherent story line. But I had enjoyed her novella Binti, so I trusted that this one might have similar appeal.

I was not disappointed by Akata Witch. I found it fresh and original, immediately bonded with the outsider status of its protagonist, Sunny Nwazue, and enjoyed the juxtaposition of her real world’s clash with the new system of magic she discovers through an unusual personal experience and the intervention of a friend from school and a neighbor to whom he introduces her.

Two of my students mention in their reviews how the book harks back to Harry Potter for them, or that they saw this parallel that has been pointed out by some reviewers. I’m assuming this is because it’s a group of children being inducted into a magical world, with a main protagonist who previously knew nothing of this world or her heritage or place in it. While it’s true that previous to seeing the end of the world in a candle flame (and setting her hair on fire), Sunny had no idea of the extra dimensions to which she was soon to be welcomed, which I guess you could see as parallel to Harry’s experience in going from an orphan under the stairs to a student at Hogwarts through the agency of an admissions letter and the abrupt appearance of Hagrid at his door, that is where the similarity ended for me. In the Potter books, once the children are transported to Hogwarts they enter a closed world, and they rarely set foot outside it for their subsequent years of education, having no contact with Muggles (regular people) except for their summers at home (which are mostly not portrayed in the books in any detail). Conversely, in Sunny’s world the Leopard People (those who possess magical abilities) live in the midst of the Lambs (regular people), and must be diligent to both keep up appearances in that world and keep their juju, their extra dimension of skills, beliefs, and magics to themselves.

This brought up yet another interesting point, from one of my students, Natalie M., who advanced the theory that Akata Witch is magical realism. I initially balked at that idea—it’s paranormal fantasy, I said—but then, as we discussed and tried to pin down the various aspects of magical realism, I realized that the story did fall into the classic definition: A book that is essentially realistic, into which magical elements are introduced as matter-of-factly as the day-to-day. I liked this quote I found in an excellent article by Kelsey McKinney in Vox:

Unlike in fantasy novels, authors in the magical realism genre deliberately withhold information about the magic in their created world in order to present the magical events as ordinary occurrences, and to present the incredible as normal, everyday life.

Some of the things I liked about the book:

The outsider status of the protagonist. She is different from those around her in so many ways: She was born in the United States, but to two Nigerian parents, who later return with their family to Nigeria (when Sunny is nine), so she has been raised as some hybrid of the two and is ostracized for it; she is an albino, with yellow hair and skin “the color of spoiled cream,” so one difference is constantly on display; she is a girl who excels at soccer but isn’t allowed to play, for both misogynistic and physical reasons (she burns too easily in the sunlight).

The world-building: The story-telling felt so fresh to me, I think, because the world is so obviously not America-centric. The day-to-day events, the culture, the places they visit and the descriptions of those places, the clothing, felt distinctly like something I had never previously experienced, and I enjoyed that.

How the magic works: While the four main characters—Sunny, Orlu, Sasha, and Chichi—are expected to adhere to certain standards in their magical learning and practice and not trespass on forbidden areas, there is not the feeling that their teachers or mentors are attempting to impose conformity on them—rather, they are celebrated for their diverse aspects, and their talents actually follow from them. (For instance, Orlu’s dyslexia makes him an adept at unworking or undoing spells.) There are certain messages here that are often neglected in worlds in which people somehow attempt to master or dominate magical abilities; in this one, the pursuit of power for power’s sake is discouraged, as is perfectionism, particularly comparing one’s own mastery to the progress of others. While there is some system to the magic they practice (gaining knowledge through books, through personal instruction, and through experimentation), there is never any complacency about “how things work,” because the juju can go rogue at any moment, setting up both the magical world and the world as a whole as unpredictable and not to be taken for granted. And I loved some of the details, such as the “chittim” (currency) that rains down on someone for learning something new, having a valuable insight, or successfully performing in a challenging moment. It seemed just the right method of positive reinforcement.

Although some reviewing this book find disturbing the disregard the older Leopards, the mentors, seem to have for the safety of the four when it comes time for them to confront their Oha challenge by defeating Black Hat Otokoto, I actually found that an additional piece of evidence that this is a world based on realism: The mentors fully realize the danger into which the children go and, granted, seem a bit ruthless when considering their fates, but they also recognize that the unpredictability and serendipity of sending these mostly untried practitioners up against this powerful villain may have a good result where calculated measures have failed.

Based on this first book, I think this is a wonderful tale to add to the “canon” of magical systems in teen fiction, and look forward to what the other two books in the series will reveal (if I can ever access them from the library’s extensive holds list!).

Ambivalence and vampires

After not quite embracing the witch book, I thought I’d give some vampires a shot, as my last read of October. But the one I picked…well, let’s just say it’s not what anyone would expect from a story about the undead.

Matt Haig’s The Radleys features a middle-class family living a somewhat suffocating existence in a small, declining village in North Yorkshire. Helen and Peter used to travel in the fast lane in London, but decided, once they married, to move to suburbia to raise their children, Rowan and Clara, who at this point are both in high school. Helen seems like your classic up-tight suburban mom, while Peter is showing signs of mid-life crisis in his yearning after his neighbor, Lorna. Rowan is painfully shy, has a nearly constant headache, suffers from various skin rashes, and is bullied relentlessly by the jocks at his school; Clara is trying to save the planet by going vegan, but nothing she eats seems to agree with her poor stomach, and she gives a convincing imitation of someone suffering from bulimia.

Despite her poor health, however, Clara still has the spirit of the rebellious teenager buried deep within her, and manages, in a moment of inattention from her father, to get permission to go to a party. This proves to be the pivotal event of the story: A drunken lout attacks her and tries to rape her, and she bites him on the hand with which he is covering her mouth. Suddenly, Clara is no longer feeling weak and sickly, and manages to fight back very effectively…because the one thing their parents neglected to tell Rowan and Clara is that they have made the choice for the family to live as “abstainers,” but what they are denying is vampirism! When Peter calls upon his brother, Will, an unregenerate blood drinker, to come sort out the tricky situation with Clara, their secret, restrained lifestyle is upended and new choices have to be made.

Well, first of all, I was somewhat disappointed because I picked out this book based on the name—I thought maybe someone had written the back story for the character of Boo Radley in To Kill A Mockingbird! (You have to admit that it would make sense for the pale and reclusive Boo to turn out to be a vamp!) No such luck. Maybe someone will write it someday, however, after this book in which the name “Radley” is revealed to be that of an old vampire family of natural-borns.

The premise of the book—that vampires could choose to be “vegetarian”—echoes the choices of the Cullens in the Twilight saga—no eating the neighbors, utter secrecy, etc. But in those books everybody gets to choose, while in this one Rowan and Clara are miserable because unaware of and without access to their true natures. Also, although everyone in the family (except the martyr Clara) eats a lot of meat, it doesn’t seem to be an option to drink animal blood, which I found peculiar.

The truth is, this isn’t so much a book about vampires as it is about bourgeois values: The well-behaved Brits are fighting their baser instincts in order to lead an upstanding existence by engaging in a lot of typical repression. What it is they are repressing is supposed to make it more interesting, but I felt like that in some ways they were just too stereotypical to make it work. The middle-aged malaise about sex with one’s long-term partner, the yearning over the forbidden neighbor (or wicked brother-in-law!), the hasty steps taken to keep what’s really going on a deep dark secret—even from their children—doesn’t explore much new ground. I was thrilled when Clara finally bursts her restraints, but that had to be covered up like everything else.

The various temptations that present themselves once the truth comes out result in both triumphs and tragedies for the conflicted Radleys, and there is an eventual resolution…but by the time it happened I had become wearied by all the dithering. The writing is both descriptive and clever, and there are some dark moments and some redemptive ones that appeal, but ultimately it felt like just another story about child abuse, with parents deciding for their children who they are to be without ever consulting them. That may sound like a harsh conclusion to draw, but when you find yourself applauding as the dainty teen protagonist takes large chunks out of the school bully, well…there’s just something not quite right about that!

Witchy? or whiny?

I will be teaching Young Adult Literature at the UCLA library school again this coming spring quarter, so I am starting to gear up for that by trying to catch up with a couple of years’ worth of teen fiction. Although I teach the history of the literature, I also like (and need) to be up on the latest thing in as many genres as possible. This week I chose a fantasy/paranormal by a first-time author—The Nature of Witches, by Rachel Griffin—partly because, well, it’s October! Time for witches.

The book has an interesting premise: There are weather witches, who are each attuned to a particular season—Spring, Summer, Fall, or Winter—and their gifts allow them to manipulate both the weather and the well-being of the earth, in ways that specifically relate to that season. So Spring-born witches, for instance, are skilled at digging their fingers into the earth and making plants spring from seeds and grow to maturity in whatever time period they wish, while Winter-born witches are better at manipulating water, making it rise up out of the ground into the atmosphere, creating storm loops that provide more precipitation. All witches draw their power from the sun.

In their world, as in ours, the populace is in general ignoring climate change, and its effects are worsening. In this story, the depredations to the earth by greedy developers and exploiters are beginning to outweigh the witches’ abilities to preserve the status quo, and witches are burning out attempting to keep the earth from spiraling into a decline. The general population of non-witches are called “shaders.”

The protagonist of the book is Clara, who is a rare and special “Ever” witch—that is to say, she has an affinity with all seasons, not just one, and can use her powers no matter what the season, while those identified with a particular quarter of the year are powerful during those three months and much more helpless during the other nine. But Clara doesn’t have good control of her powers; she has, in the past, injured or killed people when she unintentionally diverted her power and overwhelmed them, and as the book opens, she is considering staying outside during a total eclipse, which would strip her of her powers, in order to be able to live a normal life. But the fact that she is an “Ever,” able to work in every season and to harness powers not available to regular witches, means that this would be an incredibly selfish act on her part, so she is torn.

On Goodreads, I rated this a three, for concept, and also for some of the truly beautiful visual images the author presents as a part of her earth-loving witches’ consciousness. But you could definitely tell that this was a first effort on the part of the author, without some of the world-building skills necessary to a good fantasy, and also with a particular kind of teen vibe that, while common in YA Lit, is neither endearing nor enjoyable.

I loved the idea of weather witches, and having them be identified with one season, with all those season’s priorities and perspectives, was effective. Also effective was to have the one “special” witch, the “Ever,” as the protagonist. So far, so good. But to characterize everyone not a witch as a “shader” and give so little attention or perspective as to who the “shaders” are (yes, we know, the “common person,” but there’s a big spectrum there!) was to slight the entire background of the story.

First of all, am I being obtuse when I don’t comprehend how the word “shader” relates to ordinary non-witchy people? I don’t get the term. Second, although it is mentioned multiple times that the shaders have ignored the limits of the witches’ abilities to maintain the world in their eagerness for continued expansion and growth, there is little attention paid to how those communications between the two factions take place, what specific warnings have been delivered, who is in charge, etc. There are a couple of organizations mentioned by name and subsequently by initials that you have to keep looking up because they are so unmemorable, but nothing is included about their interactions except that, latterly, shaders are “beginning to pay attention.” Not good scene-setting. We needed more detail, some history of association, some BACKGROUND.

As for my second caveat about the specific teen nature of the protagonist…what I am talking about is a self-involved view of the world that relates anything and everything back to the feelings and emotions of the main character. The world revolves around her, and her obsession with her powers cuts in front of any regard she may have either for her loved ones or for the world at large. Yes, she spends a lot of the book protesting that she would give up her powers in order to keep her loved ones safe…but then she continues on, justifying and hedging her bets and putting them in danger anyway, only to cut them off again when playing with her powers gets her in trouble. And she continues to muse fatalistically on the necessity for her to be stripped of her powers in order to live a happy life, regardless of how it would deprive the earth at large of a savior of whom it has desperate need. In other words, she’s selfish, self-involved, myopic, and kind of whiny!

Far from being reserved to this particular book/author, this kind of character is prevalent in a percentage of teen-directed fiction, and although a certain amount of the observation of teen behavior and (lack of) emotional maturity may be true and accurate, it’s not fun to read. I’m not saying that authors shouldn’t write teens authentically, only that there might also be a little bit of aspirational imagining of them as rising above those thought patterns and behavior, and not at the end of an interminable 300+ pages but nearer the beginning!

This book got some enthusiastic five-star ratings, and I’m betting a lot of those are from teens who felt the romance and allure but didn’t mind the erratic and selfish thinking so much. But I would have enjoyed more back story and less angst. I call this “dithery fiction” because we spend the entire book listening to the character saying “what if” but taking forever to settle to a decision. Yes, she shows moments of resolution…which dissolve like sugar in water at the first sign of opposition, and then it’s reset: start over, dither some more. It’s ultimately so tiresome that it makes it hard to enjoy the rest of the story.

(I did like the cover image!)

in the meadow where she and Sang meet.

Mostly ghostly

I promised ghostly goodies in honor of Hallowe’en, so let’s review some titles that will have you thinking of the mysterious barrier between this world and the next, and what happens when that barrier falters!

First off is a series that was written for middle school teens but that delights everyone who reads it: The Lockwood & Co. series by Jonathan Stroud. The first book is called The Screaming Staircase, and it lays out the scenario that prevails in the other four books:

For more than 50 years, England has been overrun by ghosts. They linger, they float around, they make horrifying noises, they haunt specific places and, in some cases, they reach out to touch the living, which “ghost-touch” is nearly always fatal. The most frightening aspect of this wholesale haunting is that while adults can experience some of the effects, they can’t actually see the ghosts and therefore can’t protect themselves. So a bevy of teens and children (who CAN seen them) are recruited and armed with silver chains, salt, lavender, swords, and holy water and sent out in teams to lay the souls to rest by measures merciful or stern.

Psychic Investigation Agencies, mostly run by adults, are in charge of these teams of teens; but one young man decides that the adults who can’t even see the threat shouldn’t be in charge of his fate, and starts his own agency, run by and employing only teenagers. Anthony Lockwood, George Cubbins, and Lucy Carlyle do their best to prove they can fight ghosts with the best of the prestigious and powerful organizations against which they are competing for business, but a series of hapless incidents puts their fate in question. Then they get the chance to spend the night in one of the most haunted houses in England…

I’m baffled as to why the reviewers insist that this series is “for a younger audience.” In fact, the recommendation for 4th through 7th grades is wholly inappropriate—the 4th-graders would be too frightened! I would say 6th grade and up…and up. I found the mysteries engaging, the haunted scenarios truly frightening, and the world-building completely believable. I think anyone would like these. The other books are: The Whispering Skull (pictured above), The Hollow Boy, The Creeping Shadow, and The Empty Grave. (Another bonus: The series is complete! No waiting around for sequels.)

Now for another book that is also YA, but doesn’t seem so in the reading: A Certain Slant of Light, by Laura Whitcomb. Helen and James are two spirits who are haunted by a few hazy, incomplete memories of their pasts (when they were alive), and need to remember who they are and how they died, and figure out why they are in this strange limbo between life and death. Helen, who is 130 years past her due date, has discovered that when you are “light,” in order to keep from plunging into some kind of horrific afterlife you need to cling closely to a human host. Her latest is an English teacher, Mr. Brown, and it is in his class that she encounters James, the first person who has been able to see her since she died. There’s a reason for that: James is also “light,” but has found an ingenious way to live again.

I don’t want to give away much more than that, but if you are thinking this sounds like a Stephenie Meyer plot, think again: It’s far more than a sappy teen romance. FIrst of all, Whitcomb’s writing is witty and sophisticated, and the story itself is surprisingly complex, exploring such themes as human existence, forgiveness, and the emotions of love, grief, and responsibility. The personas are carefully crafted to relate to their relative time periods, Helen’s formal speech contrasting beautifully with James’s more contemporary lingo. Whitcomb is also a master at describing the sensations the characters feel as they experience certain things for the first time. I found the story arc deeply satisfying when I read the book, and only recently discovered that there is a second book, called Under the Light. I was surprised, since a sequel didn’t seem necessary, but the description reveals that it’s more of a companion novel, telling the stories of two other deeply invested characters, and I intend to grab it just as soon as I reread this one so that I remember all the necessary details!

Note; Whitcomb has another book that sounds like it would be spooky, called The Fetch. My recommendation is, don’t bother. It’s more about the Russian Revolution than anything else.

Another young adult series that offers up some spooky situations is the Shades of London series, by Maureen Johnson. In the first book, The Name of the Star, Louisiana teen Rory Deveaux has arrived in London to start boarding school just as a series of murders directly mimicking the crime scenes of the notorious Jack the Ripper are taking place. Despite a number of potential witnesses, it seems that Rory is the only one who spotted the man responsible for these heinous crimes, for a surprising reason that puts Rory in imminent danger. In the other two books—The Madness Underneath, and The Shadow Cabinet—we move beyond the Ripper story to discover that there’s a lot more happening on the ghostly front in London than anyone without Rory’s extraordinary perspective would suspect.

Note: There was supposed to be a fourth book, but six years passed and the author seems to have moved on permanently. It’s not really necessary to continue—the story arc was satisfyingly contained within these three. People wished for new adventures for various characters, but there is no cliffhanger, the story ends.

Finally, let me mention a few stand-alone titles that provide a satisfying shiver for your backbone:

Try Graveminder, by Melissa Marr. Although she is primarily a teen author, this book was billed as her first for adults; but I think both teens and adults would enjoy it.

The story centers on the town of Claysville, home to Rebekkah Barlow and her grandmother, Maylene, and also a place where the worlds of the living and the dead are dangerously connected. Minding the dead has been Maylene’s career and, once she dies, Bek must return to her hometown and, in collaboration with the mysterious Undertaker, Byron, make sure that the dead don’t rise. The tagline of the book is “Sleep well, and stay where I put you.” Deliciously creepy!

Break My Heart 1,000 Times, by Daniel Waters: A suspenseful thriller in which a “Big Event” has happened in the nearby metropolis, and all the resulting dead are lingering instead of moving on. Veronica and her friend Kirk have recently noted that not only are the ghosts not moving on, but they seem to be gaining in power. But when the two decide to investigate, they draw the sinister attention of one of Veronica’s high school teachers, who has an agenda that may include Veronica’s demise…

Meet Me at the River, by Nina de Gramont, is told from two viewpoints, that of Tressa, trying to cope with the death of her boyfriend, and that of Luke, the boy who is dead but can’t leave. I don’t want to say too much about it, because I so much enjoyed discovering the facts of the story in exactly the way the author wanted, which was not immediately, not all in a paragraph of explanation, but gradually, through the interchanges, the thoughts, the scenes. I will say that this book is much more than a sad paranormal love story—it’s as deep and intense as the river in its title. I found myself humming while I was reading, and finally figured out that I was remembering the hymn “Shall We Gather At the River?”, a song they sang at funerals in my childhood, a song laden with images of crossing over, being with loved ones. So much of this book was about death, but so much about life, too.

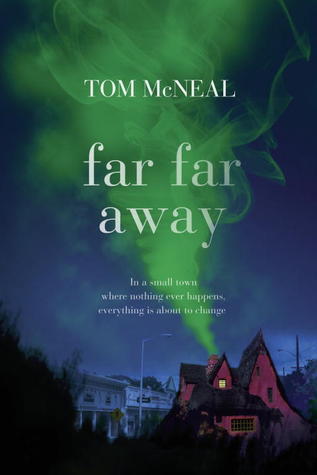

Far Far Away, by Tom McNeal: Jeremy can hear voices. Or, specifically, one voice, that of the ghost of Jacob Grimm, one half of the infamous writing duo, The Brothers Grimm. He made the mistake of admitting this once during childhood, and has been treated with doubt and suspicion by all the others in his village ever since. Jacob watches over Jeremy, protecting him from an unknown dark evil whispered about in the space between this world and the next. But when Ginger Boultinghouse takes an interest in Jeremy (and his unique abilities), a grim chain of events is set in motion. And as anyone familiar with the Grimm Brothers knows, not all fairy tales have happy endings…

For this list, I pretty much stuck to ghosts and steered clear of all the other beings that go bump in the night, but I’m going to mention one simply because it’s so much fun: Fang Girl, by Helen Keeble. Xanthe Jane Greene, a true fangirl of the fanged, wakes up one night in a coffin. Given her fantasies you’d think she’d be pleased, but no: What girl wants to preserve in eternal life such 15-year-old afflictions as acne and a puberty-born tendency to extreme clumsiness? Not to mention missing out on all the teen milestones, like getting a driver’s license and going to prom. So what does she do, upon emerging from her grave? What any 15-year-old from a loving environment would do—she goes home to her parents and little brother. Vampire lore has been done to death, but in this clever and winning parody Helen Keeble finds new territory, and it’s the perfect mix of paranormal with comedy. Don’t miss it.

I hope you will find something from this list to make your Hallowe’en reading sufficiently scary. Let me know what you think!