My Year in Books 2025

I managed to read quite a few more books this year than last (95 to 2024’s 66), but I don’t know that I realized much advantage from doing so, beyond just clocking the reading time. My stats, according to Goodreads, were:

95 books

28,425 pages read

Average book length: 346 pages (longest book 908 pages!)

Although I discovered some enjoyable reads, there wasn’t one single book that truly bowled me over or made me immediately check out another book by that author or settle in to read a lengthy series. And most of the books I did like were the lightweight ones that I ended up reading as a sort of relief between the tougher titles. Here’s a list:

The Lost Ticket, by Freya Sampson

The Busybody Book Club, also by Freya Sampson

Vera Wong’s Guide to Snooping (On a Dead Man),

by Jesse Q. Sutanto

Finlay Donovan Digs Her Own Grave, by Elle Cosimano

My favorite science fiction book was The Road to Roswell, by Connie Willis.

My new discovery in YA fantasy, with an intriguing Egyptian-like setting, was His Face is the Sun, by Michelle Jabes Corpora. I look forward to the sequel(s).

I read a few books that were award-winners, or by well-known literary authors, or touted by other readers as amazing reads, but found most of them problematic in some way, and therefore didn’t feel wholeheartedly pleased to have read them. They were:

James, by Percival Everett

The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo, by Taylor Jenkins Reid

Horse, by Geraldine Brooks

The Mare, by Mary Gaitskill

Horse Heaven, by Jane Smiley

Three Days in June, by Anne Tyler

Gentlemen and Players, by Joanne Harris

These have all been reviewed on this blog, so do a search for the title or the author if you want the specifics. None of them received a thumbs-down, but none of them lit up my imagination either.

The most disappointing part of the reading year was the letdown I felt each time I finished the next book in a bestselling series I had previously enjoyed. I read two books by Michael Connelly—The Waiting, and Nightshade—and had a “meh” reaction to both. The Grey Wolf, by Louise Penny, didn’t deliver the characteristic Gamache love, and was filled with tangents and extraneous story lines. Perhaps the least successful (for me, at least) was The Hallmarked Man, by “Robert Gabraith,” aka J. K. Rowling, which was so endlessly convoluted that I felt the need to reread it—but so long, wordy, and unsatisfying that I didn’t! I’m really hoping these authors rally in the new year, but it’s more of a “fingers crossed” than an actual expectation.

Honestly, my best and most sustained reading took place when I got fed up enough to revisit beloved books from decades past by such authors as Rumer Godden, Georgette Heyer, and Charlaine Harris.

Today I am starting on 2026, two days ahead of schedule! Onward, readers!

One fierce moggy

I forgot about my usual post of cat stories for International Cat Day (today), so I’m going to do an abbreviated one honoring a single cat from the book I’m currently reading.

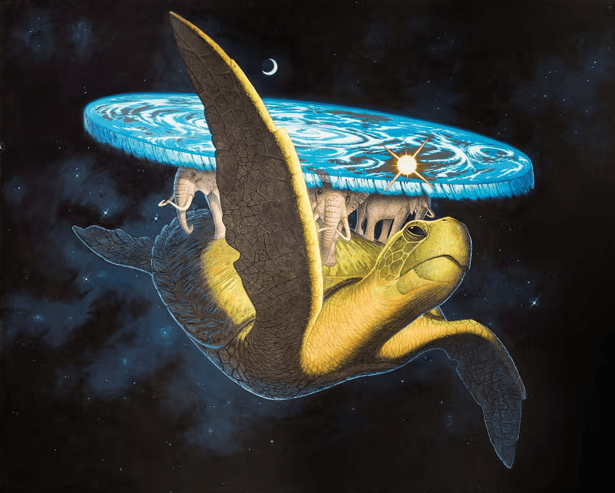

Wyrd Sisters, by Terry Pratchett, is one amongst 40-odd books of his Discworld series, but is also second of the six “Witches” books contained within that larger saga. It features Granny Weatherwax, Nanny Ogg, and young Magret, who get themselves into some good trouble when they decide to meddle with politics in the kingdom of Lancre, in which they reside.

Playing an important role in bringing together the witches with the ghost of Lancre’s former ruler is the cat Greebo. He is a one-eyed, foul-tempered gray tomcat who has aggressively fathered about 30 generations, but Nanny Ogg still characterizes him fondly as her sweet kitten (although privately she has been known to refer to him as a fiend from hell).

He features in other books of the series as well—Witches Abroad, Lords and Ladies, and Maskerade. At one point he is transformed into human form, but maintains his scars and his retractable claws, and exudes the raw animal magnetism that allowed him to claim paternity to all those descendents; but he is still handicapped by a cat’s inability to work door handles, and has an unfortunate and disconcerting tendency to groom himself with his tongue.

There are some illustrations of Greebo online, but they are copyrighted so I don’t like to poach. So here, instead, is a photo of my old feral cat, Papi, who was likewise tough, one-eyed, and prolific. He and Greebo were, as the Brits would say, fierce moggies.

Happy International Cat Day!

Pratchett

I don’t know how, in my decade-long exclusive pursuit of all things science fiction and fantasy, I managed to miss out on Terry Pratchett. I discovered some of the contemporaries to whom he is frequently compared (Douglas Adams, Piers Anthony), but it took another 30-some years and a degree in library information studies before I was introduced to him via the Tiffany Aching portion of the Discworld books. As a teen librarian, Pratchett came to my attention through the offices of The Wee Free Men; I was really taken aback when my high school book club didn’t love it as much as I did, but I didn’t let that deter me. I read every Tiffany Aching book (five total) that was out or came out thereafter, and loved them all, but for some reason I still didn’t go back (as I normally would) and explore all the other Discworld books.

Perhaps it was because of the sheer volume of the series—41 books is a lot to tackle, and I no longer read with the obsessive one-track mind that I did in my 20s, when I let nothing stop me from completing a series start to finish. But I was at extreme loose ends this week after finishing In This House of Brede; I initially moved on to another Rumer Godden but discovered that i was satiated for the moment and was craving something different. None of my holds are even close to arriving, so I went searching for something else by running my eye down my “Want to Read” list in Goodreads.

This is when I most miss being mobile; my finding process used to entail going to the library and looking at the new books and the just-returned shelves, and then wandering down aisles of my favorite genres—mystery, fantasy, science fiction—to see if old authors had new (or older) works I hadn’t yet discovered. It’s a lot easier to find an unknown treasure that way than it is to scroll through lists on the internet, as I do now that I am essentially housebound. There are the visual, physical, tactile elements of cover art, author quotes, flap summaries, the feel of the paper, the choice of font, the smell of the book, all of which yield up something that helps me make a decision. By comparison, it’s a sterile (and also endless) process to scroll through (sometimes erroneous) Goodreads descriptions, look at the ratings posted by other people, and speculate about whether I can choose something just based on these paltry factors.

This is partially what took me to Terry Pratchett—there was at least some experience, some familiarity with his story-telling and writing style, his characters, his world-building. I did pay heed to several people who said the first two books in the Discworld series, while introductory, were not his best writing, and that to start with #3 was a good beginning, particularly because it is also the debut of Granny Weatherwax, with whom I was already familiar from the Tiffany Aching books. So I acquired a copy of Equal Rites from Kindle Unlimited, and began my exploration of Discworld.

One thing you forget, if you go long periods between Pratchett tales, is his sense of humor and how he exploits old sayings, puns, wordplay. And even though Pratchett’s powers developed exponentially as he wrote each subsequent book, the humor is here from the beginning. The first one I wanted to write down the instant I read it was when Granny Weatherwax decides to find accommodations in a new town; she comments that she has specifically elected to live in an apartment next door to a talented and successful purveyor of stolen articles, because she has heard that good fences make good neighbors. Ba dum bum.

Equal Rites is the story of young Eskarina, who is mistakenly selected to be an heir to wizardry. A wizard comes to Granny Weatherwax’s village of Bad Ass seeking the child to whom he is to hand over his staff before his imminent demise; the smith of the town is an eighth son whose wife is about to give birth to his eighth son, which is highly propitious. So when the wizard realizes he has six minutes to live and Granny, having just delivered the baby, carries it into the room, the wizard places the child’s tiny fingers on his staff to claim it, and then expires before he can discover that the eighth son is actually a girl.

On Discworld, gender equality is a dream—at least for women. Only men are wizards, just as only women are witches. Men have, of course, tried being witches (because they don’t take no for an answer), but it has never worked out well; but those same men have banded together and insisted that “the lore” absolutely forbids women to be wizards, and no woman has ever been admitted to Unseen University as a candidate. Granny W, however, is determined that Esk should at least have the chance (as is Esk herself), so the two set out on a journey to the city of Ankh-Morpork, for Esk to try her luck. This is the basis for the chaotic hijinks that ensue for the remainder of the book.

I really enjoyed both the introduction to Discworld and the reacquaintance with Granny W. (and with Pratchett). I think I will continue on for a while; they say you can just read the “witch” books (of which there are six) on their own, but I might also branch out into other characters’ tales set on this flat world carried on the back of a giant turtle and four elephants.

Indy lassoes some humans

I just read a book recommended to me by my friend Kim, who is as much (or more?) a fan of science fiction writer Connie Willis as I am. I hadn’t heard of this one (and apparently of a few more, once I reviewed the list at the back of the book!), and I’ve been wanting a good new sci fi comedy (my last one was by John Scalzi), so I settled in this past week with Willis’s The Road to Roswell. I was surprised to discover that it was published less than two years ago; when Kim recommended it, I just assumed for some reason that it was an older book, perhaps because Roswell was a lot more popular setting a couple of decades ago than it seems to be now.

There were, contained within this book, both some unexpected and some entirely expected elements. The unexpected one was the nature of the alien. Not a Gray, not a Reptilian, he instead looks sort of like a tumbleweed (good camouflage in the desert!), a round shrub with branch-like tentacles; but when he wants to accomplish something, those tentacles stretch and flex and flatten, and shoot out to grab and hold whatever he is aiming to control. One of the protagonists thus gives him the nickname “Indy” (after Indiana Jones and his bullwhip).

The expected element was the nature and structure of the narrative. Connie Willis creates this peculiar kind of interaction in many of her books—sometimes subtle, more often extreme—in which communication between characters is constantly stymied. People start to say things but get interrupted. People mean to tell other people important information but forget, or get sidetracked, or are ignored. People try to pass on messages through a third party, who misunderstands and misinterprets them or, again, forgets all about them. The result is an ongoing escalation of tension over the missed opportunities, especially as questionable situations are further exacerbated by the ongoing lack of understanding. It results in a story full of dialogue that fails to move the action forward as intended, and when I read one, I find myself needing to take a break now and then to allow the anxiety from the escalating tension to subside!

This book begins with Francie, who has flown into Albuquerque and rented a car to drive to Roswell, New Mexico, where she will (maybe) be serving as maid of honor to her college roommate and best friend, Serena. It’s only a maybe because Francie has been in this position with Serena several times before, but no wedding has yet taken place; Francie’s role seems to be showing up in the nick of time to talk Serena out of marrying whichever oddball nut job for whom she has supposedly fallen head over heels. In this instance, it’s a UFO-obsessed alien-chaser who thinks the best venue in which to celebrate their marriage is the International UFO Museum.

Imagine Francie’s surprise, therefore, when aliens turn out to be real. She finds this out when she and her rental car are commandeered by one, who wants to go somewhere (although he can’t communicate where) and needs Francie to serve as his chauffeur. Soon, while on their surprise road trip, they also acquire a hitchhiker (maybe a grifter), Wade; an hysterical guy obsessed with alien abduction conspiracy theories; a little old lady on a bus trip to the Las Vegas casinos; and a retiree whose enormous RV becomes their new vehicle when Francie’s rented Jeep will no longer accommodate everyone the alien decides to lasso and bring along on this adventure.

Despite the kidnapping aspect, Francie and the others (except for the conspiracy guy, who can’t stop talking about invasions, probing and Men in Black) become convinced that “Indy,” as they call him, is in trouble and needs their help to get out of it. They go from unwilling abductees to a team devoted to understanding and helping their new friend, as they drive all over the southwest looking for who-knows-what and encountering rattlesnakes, Elvis impersonators, and people and aliens who may mean them harm. The book is a frenetic mix of abduction, expedition, and romantic comedy, and it’s fun. Really fun. If you need a silly story that also encompasses the best and worst of human foibles as illustrated by their reaction to aliens in their midst, this is one to read.

Harking back

Somebody on Friends and Fiction (Facebook group) asked for a list of time travel books and, amidst the ones by Connie Willis, Diana Gabaldon, and Bee Ridgway that I have cataloged, I saw an old favorite from the late 1970s and decided to do a reread.

The book is The Door Into Summer, by Robert Heinlein, and it has the distinction of having been written in the 1950s with the expectation that by the 1970s we would already have things like autonomous robotic vacuum cleaners (i.e., android-shaped Roombas), and by the year 2000, well, sky’s the limit—teeth that regenerate, cream that removes a beard, “stick-tite” clothing fasteners (fancy velcro) and so on. It’s kinda fun to hark back to early science fiction and see the optimistic expectations with which the authors pictured our world. We still don’t have those hoverboards from Back to the Future, let alone a lot more practical gizmos, and humans haven’t colonized any other planets just yet, but on the other hand we do have stuff (like the internet and various fancy Apple products) that none of those sci-fi writers ever envisioned.

In this particular book, the protagonist, one Daniel Boone (D.B. or Dan) Davis is an engineer who retires from the military and hangs out his own shingle with his best friend Miles Gentry, with Dan doing the designing of fancy housewives’ helper-type machines while Miles (a lawyer) runs the business end. They are shortly in need of an office manager/secretary type, and hire Belle Darkin, with whom Dan immediately becomes romantically involved. Dan, being a mechanical genius but otherwise a naive trusting soul, leaves the daily doings to these two, who are up to some behind-the-scenes shenanigans and ultimately cheat Dan and expel him from the company. Dan, having lost both his life’s work and his fiancée, resolves to take “the long sleep,” which is basically cryogenic freezing of people, for 30 years. The idea is that you invest your money, go to sleep, and wake up however many years later with your investments having paid off, still young enough to enjoy them. But do these kinds of things ever work out as promised?

Two additional crucial characters are Dan’s cat, Petronius “Pete” Davis, and his (former) buddy Miles’s stepdaughter, Ricky, a precocious 11-year-old who adores both Pete and Dan. Since I have already perhaps given away too much of the story (although there’s a lot more to it), I’ll say no more about the plot. The title of the book comes from an anecdote about Dan and Pete; they lived at one point in an old farmhouse with a dozen doors, and in the cold and snowy winter-time Pete persists in crying to be let out of each door in turn, getting progressively more agitated that one of the doors doesn’t lead to better weather—obviously a metaphor for the rest of the activity in the story.

Heinlein is at once revered and denigrated for his career as a science fiction writer. On the one hand, he wrote some of the best “hard” science fiction stories (meaning he valued scientific accuracy in his books) from the period between 1941 and 1988 when he died (he was born in 1907). But he was also derided for his right-wing ideology, for the rampant misogyny (the condescension is palpable) in his books, and also for a kind of creepy obsession with very young women, all of which got more radical as he aged. This book has a bit of that (the focus on Belle being primarily on her buxom figure), but mostly it’s just a fun and offbeat story about the possibilities of time travel from dual aspects, and (with the caveat that parts are laughably old-fashioned) I wouldn’t hesitate to recommend it (as Heinlein himself would probably characterize it) as a “cracking-good” read, a nice change of pace from today’s fiction offerings. I seem to have been afflicted, as I read it, with a quaint language “bug,” so I’ll say give it a whirl.

Wrapping up

This year it feels more like a winding down than a wrapping up. I read the fewest books in one year since I started doing the Goodreads Challenge 12 years ago. That year I read 75 books; my highest number ever was in 2019, when I read 159 books while working full-time from January to October (I retired from the library in October of that year). You would think it would be the reverse, since I have so much more time now than I did then; but there were some factors at play that ensured I would read a lot more then. First, I was running three teen book clubs, so I had to read one book per month for each club, plus a couple extra books in each age range (the clubs were 6th- and 7th-graders, 8th- and 9th-graders, and grades 10-12) so I would have ideas to propose as the following month’s read. I was also reviewing books for both the teen and adult library blogs (both of which I supervised), so I was heavily invested in spending all my spare time reading new teen and adult fiction to showcase there. And finally, of course, there was a certain amount of reading for my own particular pleasure! I basically worked, commuted, ate, slept, and read, and did absolutely nothing else!

Nowadays there are circumstances that tend to decrease my reading time: With my particular disability, sitting in one position for long periods of time isn’t great for keeping my legs at their best possible condition for mobility. I also watch a lot more on television these days, now that streaming services let you binge-watch an entire five-season show, one episode after another for as long as you can stay awake, as opposed to waiting for one weekly episode for a 12- to 20-week season and then waiting in turn for the following season. And I spend way too much time “doom-scrolling” political stuff online, or keeping up with friends on Facebook. Finally, once I took up painting I started spending at least a few days a week focused on making a portrait or two or a still life featuring items from my antique collection.

Anyway, this year I read a meager-for-me 66 books. Some of them were literary and some of them were chick lit, some were re-reads of beloved stories, and others were authors previously unknown. My statistics include:

23,782 pages, with an average book length of 360 pages

(shortest was 185, longest was 698)

Average rating was 3.6 stars

Some favorite new titles were:

The Unmaking of June Farrow, by Adrienne Young

Starter Villain, by John Scalzi

Vera Wong’s Unsolicited Advice for Murderers, by Jesse Q. Sutanto

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, by Becky Chambers

All the Dead Shall Weep, and The Serpent in Heaven, by Charlaine Harris

Found in a Bookshop, by Stephanie Butland

I felt throughout the year like I was having trouble discovering books that really resonated with me. Although I had some pleasurable reading discoveries, I never found that one book or series or author that really sucked me in and kept me mesmerized for hours at a time. I found myself reading during breakfast or on my lunch break and easily stopping after a chapter or two to go do something else, rather than wanting to settle in for a solid afternoon of reading. I’m hoping to find more compelling books in the new year. But reading continues to be one of my best-beloved pastimes.

Alien encounters

John Scalzi is a funny guy. It took me awhile to reach this conclusion, because when I began reading his books, I didn’t approach them in chronological order; my first experience was with his robot/murder-mystery book Lock-In, and after that I read the whole “Old Man’s War” series, which (apart from a few bad puns and tongue-in-cheek moments) is relatively serious in nature. But then I found Fuzzy Nation, Redshirts, and The Android’s Dream, and realized he has a well developed sense of humor. And this past week I perused his backlist and found his very first novel, called Agent to the Stars, which both solidified that opinion and also reminded me of a whole vein of science fiction (alien encounters) that I have consistently enjoyed. Some of them take the subject seriously, while others (like this one) treat it with a fun and refreshing lack of gravitas.

Agent to the Stars follows a premise that I first encountered in Sheri S. Tepper’s book The Fresco—

the question of what would happen should extraterrestrials make contact with one ordinary human, rather than going the more accepted route of approaching the government of some country or the Secretary-General of the United Nations, i.e., an official body or representative. In this case, said extraterrestrials arrive at the conclusion, after long-term absorption of radio and television and movie broadcasts, that Hollywood is the all-powerful entity in our world, and the best way, therefore, to spring themselves upon mankind is to get the entertainment industry to pay attention; they therefore hire themselves an agent to represent them (as one would).

They first contact the head of a powerful agency, but his visibility may attract too much attention while decisions are being made about how to make palatable a group of aliens who are essentially shaped like big piles of Jello with extrudable tendrils and smell really bad, so he passes the responsibility down to his most successful brash young agent, Tom Stein. One of the Yherajk thus becomes Tom’s constant companion in the quest to exchange knowledge between the two races, and this association becomes a comedy of errors that encompasses an aging golden retriever, a vapid young starlet, a persistent tabloid journalist, and a completely implausible but thoroughly entertaining series of events, as Tom and the alien representative try to figure out how to introduce the Yherajik to the world at large.

If this topic appeals to you, here is a small sampling of alien encounter fiction in several categories, both serious and humorous, that you might also like to explore:

TYPICAL EVIL ALIEN SCENARIOS:

The War of the Worlds, by H. G. Wells—In this classic, an army of invading Martians seeks to end human civilization. Extensively treated on radio and film as well.

Starship Troopers, by Robert A. Heinlein—A space opera drama pitting the Terran Mobile Infantry against “the Bugs.”

Ender’s Game, by Orson Scott Card—A much more nuanced version of Heinlein’s story, with young children playing computer-simulated war games that refer to the 100-year-long war with the “Buggers.” The difference here is, there are sequels in which Ender speaks and acts against xenophobia…

Binti, by Nnedi Okorafor—portrays an encounter with the Meduse, “an alien race that has become the stuff of nightmares.” (two sequels)

The Three-Body Problem, by Liu Cixin—A secret military project seeks to contact aliens, but the ones they find are on the brink of destruction and decide to invade Earth and take it over. (two sequels)

EQUIVOCAL ENCOUNTERS

(the aliens are “good,” or at least well-intentioned, but seek to alter the humans somehow):

Childhood’s End, by Arthur C. Clarke—the classic “aliens as interventionists” story that arguably begat all the others…

Dawn, by Octavia E. Butler—The Oankali save humanity from atomic destruction, but want to genetically merge with their “primitive civilization” to create a new species. (two sequels)

Human 0.4, by Mike A. Lancaster (YA)—a twist on an “invasion of the body-snatchers” scenario. Smart, fast-paced, thought-provoking. (one sequel)

The Host, by Stephenie Meyer—She’s not the greatest writer, but she is a good storyteller. The Earth has been invaded by a species that take over the minds of human hosts while leaving their bodies intact. A treatise on cooperation vs. autonomy.

The Sparrow, by Mary Doria Russell—One could argue about the category for this one, but it’s a mesmerizing tale, regardless. A scientific expedition of Jesuits make first contact with extraterrestrial life. (one sequel)

BENIGN/POSITIVE AND/OR HUMOROUS ENCOUNTERS:

The Left Hand of Darkness, by Ursula K. LeGuin—LeGuin wrote a group of books called “the Hainish Cycle,” which depict humans’ absorption into a growing intergalactic civilization (the Ekumen). One of the most famous—and arguably the best in terms of intellectual science fiction (it won both the Hugo and the Nebula)—is this book about a human envoy sent to conduct a first encounter with the inhabitants of the planet Gethen, a race of genderless, intersex beings. It’s fascinating, thought-provoking, but also deeply emotional.

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, by Douglas Adams—extremely silly and inventive. (five-book series)

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, by Becky Chambers—my review of the first book is here. (five-book series)

The Fresco, by Sheri S. Tepper—This is the one I immediately remembered when I started reading the Scalzi book I just reviewed. Latina single mom Benita Alvarez-Shipton is approached by a pair of aliens who ask her to be the sole liaison between their race and humans. First up, she has to contact the Powers That Be in Washington and convince them she’s not crazy.

I hope you find something here that will cause you to enjoy this aspect of the science fiction galaxy!

The long way

I just finished reading The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, by Becky Chambers, author of the Wayfarers and the Monk & Robot books. This one is the first of four in the Wayfarers series, but it’s not obvious at all while reading it that it’s the start to a longer story. The only reason I might have surmised that is the overwhelmingly character-driven nature of this book, in which many things happen and lots of people/races are introduced but there is not a truly cohesive story line. That’s not to say that there isn’t a kind of evolution from the beginning to the end, but…is it a story? It feels more like a bunch of separate people’s narratives coming together simply because they are co-located in the enclosed space of a ship and a voyage, but while they do have an impact on one another, there isn’t the same kind of resolution that there is to a typical beginning-middle-end kind of tale with a sole protagonist.

The event for which the book is named takes up not very much space in the overall timeline, which is kind of odd. Can you tell that I’m finding it a bit hard to review this book? I think it’s because, while I liked many of its diverse elements (including its diversity!), they didn’t gel for me in a way that would have made me love it. And although I liked and had empathy for its characters, I’m not sure any of them made the kind of impression that will make me want to read more about them in subsequent volumes. I finished the book with a certain degree of satisfaction, but it was more the feeling of “I’m good” than a compelling desire to keep going.

That is both the strength and the weakness of this book; because the story is about half a dozen (okay, maybe eight or nine) individuals who alternate in carrying the narrative, you learn a surprisingly extensive amount about the various kinds of “people” populating the universe without thoroughly investing in any of them. There are a few characters that have more page time and are therefore more engaging and involving than the others, but it’s a bit didactic in the way it goes about portraying everyone, and some of them end up being more cliché than person.

On the other hand, the number of issues and the depth and breadth with which they are explored is impressive, and not too heavy-handed. The involvement between species readily lends itself to discussions about topical and complicated subjects, from identity, sexuality, and violence to safety and defense, the implications of sentient artificial intelligence, and what constitutes “community.” I enjoyed the many variations of people (both their inner natures and outer appearances) that Chambers created, and the fact that none of them was stereotypical or relied excessively on science fiction that has gone before.

I guess I should give a brief synopsis, to be thorough, in case someone finds this blah blah intrigues them! It begins with Rosemary Harper, a human who is fleeing some personal issues and answers an ad for a position as clerk on the Wayfarer. It’s a tunneling ship, a kind of spaceship that creates wormholes to connect distant points in the universe so travel and trade can more easily take place between species. The story is set in a galaxy of aliens, with the humans being a sort of on-tolerance, minor group. There are a couple of older races with a history of expansion, cooperation, and development who have created the Galactic Confederation and brought in other member species at various points in their own maturity. There is a fair representation of these different species amongst the crew of the Wayfarer, and the philosophical bits of this “space opera” vehicle are about how they learn to cooperate and to appreciate one another. The ship is offered a contract to create a tunnel near the galaxy core that connects to a previously interdicted warlike species, and the build-up to and resolution of this contract is what drives the action, although this takes place late in the story (maybe at the 75 percent mark?).

The book isn’t for everyone; if you enjoy character-driven stories and envisioning complex alien cultures, you will like it, and the adventures of the Wayfarer gang do somewhat satisfy that yen for more stuff like Firefly. Despite its slow pacing, it was a fairly quick read, interesting and thoughtful but not taxing. Even though I’m not feeling it in this moment, I wouldn’t rule out continuing to follow the adventures of the Wayfarer crew in subsequent volumes, sometime later in my reading life.

Dog Day Afternoon

No, this isn’t a post about a 1975 bank robbery movie. But the title seemed appropriate, given that it’s National Dog Day and also that I am getting such a late start that my post won’t be available until after noon, one of those hot, sleepy afternoons when dogs (and people) prefer to lie around and languish (i.e., read!) during the summer heat. I did some pre-planning for this post by making a list of some pertinent dog-oriented books, but then my distracted brain failed to follow up, so a list is pretty much all you’re going to get this time. But don’t discount it just because it’s not elaborated upon; these are some great reads, encompassing fantasy, mystery, dystopian fiction, science fiction, some true stories, and a short list for children.

NOVELS FOR ADULTS (AND TEENS)

The Beka Cooper trilogy (Terrier, Bloodhound, Mastiff),

by Tamora Pierce

A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World, by C. A. Fletcher

Iron Mike, by Patricia Rose

A Dog’s Purpose, by W. Bruce Cameron

First Dog on Earth, by Irv Weinberg

The Companions, by Sheri S. Tepper

The Andy Carpenter mysteries, by David Rosenfelt

The Dog Stars, by Peter Heller

DOGGIE NONFICTION

Marley and Me: Life and Love with the World’s Worst Dog,

by John Grogan

Best Friends: The True Story of the World’s Most Beloved

Animal Sanctuary, by Samantha Glen

James Herriot’s Dog Stories, by James Herriot

A Three Dog Life, by Abigail Thomas

Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know,

by Alexandra Horowitz

CHILDREN’S BOOKS WITH DOGS

Sounder, by William H. Armstrong

No More Dead Dogs, by Gordon Korman

Harry the Dirty Dog books, by Gene Zion

(illustrator Margaret Bloy Graham)

Bark, George, by Jules Feiffer (one of the best for reading aloud!)

And for those who wanted more, here is an annotated list of more dog days books from a previous year, along with some suggestions for dog lovers that go beyond reading about them.