Mistaken identity

The ratings and comments on Goodreads for On Rotation, by Shirlene Obuobi, are so spot-on to illustrate why publishing companies have to be held accountable for the way they promote a book. There were a few people who thoroughly appreciated the story for what it was, which was a combination of “relationship fiction” and and the immigrant experience, with coming-of-age (early 20s variety) thrown in; the rest were disgruntled and showed that in their ratings, because the blurbs had led them to believe this was a rom-com.

Don’t get me wrong: There is a romance in this book that takes up a significant amount of air. But it isn’t a comedy (although there are a few funny moments), and it doesn’t have that coy, somewhat self-conscious vibe that lets you know when you’re supposed to acknowledge the ironies or coincidences or other plot points common to the specific rom-com subgenre.

Instead, it’s a narrative about the experiences of a young black woman in medical school; but moderating that more generic scenario is the specificity of being a first-generation Ghanian, seeing how that sensibility and those traditions differentiate a part-West African, part-British heritage from that of the American descendents of slaves. It’s a showcase for the immigrant point of view—the older generation who gave up much to move their lives to a new arena having hefty, sometimes crushing expectations of and for their children, who are perceived to have every advantage and are expected to make perfect choices. It’s an examination of friendship and love and what place and importance those two levels of engagement can have in life. And yes, it’s also a romance, but from a more complicated context than the usual rom-com fare.

On Rotation focuses on Angie, a 20-something black woman who is prioritizing her career goals and having to juggle wildly to keep up with everything else. The style is engaging, and the cast of characters is lively, diverse, and inclusive. I liked the detail of the story where she decides to enhance her chances at getting a plum residency by doing a study about how the black experience with doctors and hospitals differs from that of white patients. While I am a white woman, the fact that I have a health condition about which many doctors are ignorant and/or dismissive made me able to relate to and appreciate the information she gathered.

The challenges of trying to live up to her parents’ expectations, which are many and encompass both the significant and the trivial—including everything from her success as a doctor and her choice of romantic partner down to the tidiness of her apartment and how she wears her hair—will probably ring true for many of us, but there is definitely an added amount of pressure for children of immigrants. I loved the connections she had and maintained within her circle of “ride or die” friends, and the bewilderment and grief with which she faces the possible ending of one of those relationships. And the shallowness of her past dealings with men who appreciated certain aspects but couldn’t embrace the whole of Angie were a nice contrast to the relationship she wants but doesn’t trust with a man who may be different.

I confess that I would have preferred a little less of what was going on inside Angie’s head at all times for a little more of what was happening in the thoughts or behind the scenes of certain other characters; but this is a minor caveat—it was, after all, Angie’s story.

There was one truly irritating aspect of the book and, perhaps blessedly, something I could blithely choose to ignore: The author appends footnotes to almost every page, in which she didactically explains medical terms, Ghanian customs, black hair, contemporary slang, and everything else she must have believed the reader was either too ignorant to get or too lazy to research. But because I read this as an e-book, the footnotes all appeared sequentially at the very end of the book and, rather than jumping back and forth between whatever page I was on and the last 20 pages of footnotes, which is a major pain when reading on a Kindle, I simply gave up on knowing what she was choosing to share in those addenda, which probably saved the book for me. Footnotes in fiction are almost never a good idea unless they serve an alternate purpose, such as the ones in Jonathan Stroud’s Bartimaeus saga, wherein the main story is about the boy magician Nathaniel who summons an ancient genii, while the footnotes contain the sly side commentary of the genii himself. So I guess my recommendation for enjoying Obuobi’s book is to read the Kindle version and ignore the asterisks liberally seeded throughout the text!

Category: Coming of age, Relationship Fiction, Romance, Socially engaged fictionTags: Appeals, E-book, medical, Stand-alone

Quiet transformation

Still Life with Bread Crumbs, by Anna Quindlen, is a book that doesn’t have an initially heavy impact, but it sticks with you. It’s about a woman in a situation to which many of us in our 60s can relate: We were “somebody” once (or if we weren’t exactly prominent, we were at least identified as a certain kind of person who does a specific kind of thing, whose identity is wrapped up with that activity), and now we’re beginning a downsizing of that role; and this narrowing could be an end, or it could be an avenue for change, depending on how we react to it, how we see it through, what we are willing to allow.

Rebecca Winter was a famous photographer who produced iconic images relating to womanhood and motherhood—views of common items that grew in importance to express a certain kind of lifestyle or mindset in those who viewed them. Once, she was revered, sought out, exhibited, solicited for new works, invited to lecture, sometimes even recognized on the street. But now her sales are dropping off while her responsibilities (and bills) are growing, so she has chosen to solve the problem of her scant bank balance by renting out her costly Manhattan apartment and moving to a cheap rental in a small town in the middle of nowhere in particular. This will allow her to pay for her parents’ old age care until she can figure out what her next step should be.

It’s initially difficult for her to adapt to the dramatic change in circumstances, and she finds herself unprepared for the solitude, the immersion in nature, the lack of stimulation formerly provided her by big-city living, the inability to solve her problems by throwing money at them. But gradually she sinks into her place in this small community, finds regular routines, changes her expectations about what constitutes a success, and begins to tentatively create something different for herself. And these shifts in perspective also allow her to look at herself, her work, and her relationships in a way that finally breaks down the wall she has built between the idealized world of a woman behind a camera and the everyday experience of someone with nothing between herself and reality. It is a kind of coming-of-age story, but at the end, rather than at the beginning, of the spectrum.

Some reviewers really pick this book apart, belittling the transformative experience of the main character and calling it overly sentimental or even trite. Some also focus heavily on the May-December (well, perhaps July-December) romance, which to me was only one small element in the bigger picture being presented, not nearly as important as all the rest of it. Perhaps I am just a naive reader, or easily satisfied, but I would call this book a sort of “comfort food” read on the surface, but with strong underlying themes that give it a universal affect. I enjoyed both the superficial story and the deeper ruminations. I liked the storytelling, and tapped into the emotion, and I liked Rebecca’s authenticity and transparency, as well as the humorous side stories and anecdotes that keep the narrative lively and unexpected. It may not be to everyone’s taste, but for me, where I find myself in life, it was just the thing.

Category: Realistic Fiction, Socially engaged fictionTags: Coming of age, Stand-alone

A deep dive into fantasy

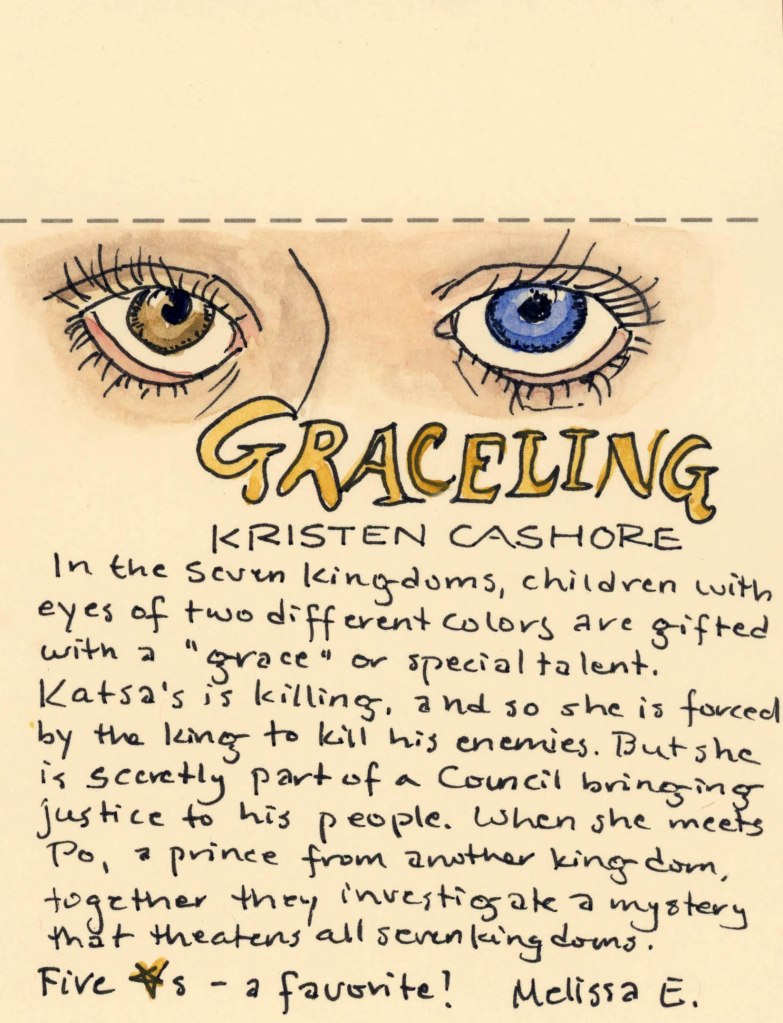

While I was a teen librarian I had the pleasure of discovering the book Graceling, by Kristin Cashore. It’s one of those fantasy books that was (perhaps) written with teens in mind but which appeals more widely to fantasy readers in general, and I recommended it, during my tenure, to as many adults as I did to teens.

A “shelf-talker” I made

Since I read it with two of my book clubs, I ended up reading the book three times, and it held up well. I was excited to read the sequel, Fire, but although I did enjoy it, it was a companion novel rather than a continuation of the story of Katsa, Po, and Bitterblue, and I was disappointed not to find out what happened to them after the conclusion of Graceling.

When Bitterblue came out, I thought, Finally! but I think I was not in the right place to enjoy Cashore’s envisioning of the continuation of King Leck’s kingdom, and I actually put the book down without finishing it, feeling disappointed in its air of quiet misery, disillusionment, and bewilderment.

I had always meant to reread it, but had no pressing reason why until I recently noticed that there were not one but two “new” sequels to the story, all still incorporating the original characters to an extent but also expanding beyond them to open up the world of the Seven Kingdoms and venture into the lands beyond. So a few weeks ago, I resolved to reread Bitterblue, no matter how lackluster I might find it, in preparation for Winterkeep and Seasparrow.

I was delighted to find that the story engrossed me, that I was able to feel the mood Cashore had wanted to convey as one appropriate to the history that came before it, and that it was no longer a letdown.

Some background: Graceling

The main character in Graceling is Katsa, an orphan who lives at the court of her uncle, a ruler of one of the Seven Kingdoms. Katsa was born with eyes that are two different colors; people who are born with this “tell” are gifted with a “grace,” a special skill or talent. It can be something silly, like the ability to open your mouth wide enough to swallow your face; something practical, such as skill with baking; or something serious, in Katsa’s case a grace for killing. In her uncle’s kingdom, it is mandatory that all children born with a grace be surrendered to the king, who makes use of their graces for his own benefit. Katsa, who killed her first man at age eight when he made inappropriate advances, is acting against her will as her uncle’s enforcer.

To counteract this, she has banded together with several likeminded people of the court (including the king’s son, her cousin Raffin) to form a secret society to help people solve big problems. While working one of these missions, Katsa meets Prince Po, who has snuck into the kingdom to rescue his kidnapped grandfather, and the two team up and plan a journey that is partially to return the old man home and partially to seek out a wrongness in a neighboring kingdom that is causing trouble to seep over the borders in every direction. Thus begins the story that brings Katsa and Po to the attention of a terrible power from which they must save the young heir to that kingdom, 10-year-old Bitterblue.

The book Bitterblue takes up eight years after the conclusion of Graceling. Bitterblue is now the young queen of Monsea, and is struggling, with the help of a bunch of stodgy advisors, to salvage her kingdom from the disaster of the past 35 years when her psychopath father, Leck, terrorized everyone under his rule. The kingdom has supposedly moved on from this dark time in its history, but Bitterblue is uneasy at the anomalies and discrepancies she discovers between the rosy picture her advisors paint for her and the truth she sees once she begins sneaking out beyond the walls of her castle and into the surrounding communities, seeking for answers.

Bitterblue is an intensely in-turned story, focusing primarily on Bitterblue herself as a ruler and on the well-being of her kingdom. But with Winterkeep, the story goes out into the world, and introspection and the minute solving of vague puzzles is replaced with new terrain, new characters, and a lot of action. Torla, a land new to the Seven Kingdoms, has been discovered, a democratic republic with two political parties—Scholars and Industrialists—and some fascinating technologies (dirigibles, for one). Bitterblue sends envoys to Winterkeep, but when she discovers they have drowned under suspicious circumstances, she decides, along with her friend Giddon and her half-sister, Hava, to travel there to discover what Torla is trying to cover up. A key player in the story is Lovisa, daughter to the two ranking heads of the opposing parties, whose position places her in a unique situation when it comes to solving secrets and helping Bitterblue and her friends.

Seasparrow takes place in the immediate aftermath of the events of Winterkeep, and is narrated by Hava, Bitterblue’s half sister, the secret and forgotten daughter of King Leck and the sculptor Bellamew. Bitterblue, Giddon, and Hava and their three advisors are on a ship bound for home, but a shipwreck in the frozen North puts all their bodies and spirits to the test. It especially becomes a personal journey for Hava, who needs to heal her childhood trauma while coming to terms with her own identity in the middle of political upheaval and a tangible threat from a frightening new technology. Although the latter is a big plot point, this book is primarily character-driven, and encompasses the healing of many different kinds of relationships, for Hava and others. I think this book, of the five, is my favorite next to the original Graceling, because of its depth of character and the nicely balanced introspection and adventure.

I’m glad I finally embarked on this continued journey through the Seven Kingdoms and beyond, and would recommend this series to anyone who likes an engaging, thoughtful, somewhat philosophical story that also happens to be set in a world where there are telepathic blue foxes!

Category: Fantasy, Saga, Socially engaged fictionTags: Coming of age, Sequel, Series

How it is

Laurie Frankel’s book is called This Is How It Always Is, I believe with the direct message (and hope) that someday it will not be this way. I am happy to say that I picked up this book without knowing anything about it, and therefore got to have the “clean,” straightforward experience of reading it without expectations. If you are contemplating reading it and okay with having its contents be a surprise, perhaps you should stop reading my review right here and go put your energy into the book instead.

If you do have some idea of what it’s about and want more perspective, or a simple reassurance that it will give you a distinctive understanding of the issue, then read on.

A few reviewers on Goodreads called this book sentimental (one even said “cloying”), but I didn’t find it so in the least. I thought it was a lovely, honest, positive depiction of the foibles of one large, eclectic family when confronted with the difficulties of navigating life in our culture.

Rosie and Penn already have a set-up that is not the norm in America: Rosie is an emergency room doctor, while Penn is a stay-at-home father working on a novel and caring for their large family—four boys, when the story opens. After having two in a row followed by twins, Rosie is longing for a girl (and fairly convinced she will finally have one), but Claude comes along and they are happy with their new baby, boy or not. But at an early age, Claude begins the show-and-tell process of becoming someone whose name for the next eight years will be Poppy.

After the initial surprise that when he grows up he wants to be a girl, Rosie and Penn step up for Claude. He is allowed to wear what he wants, play how he wants, and call himself the name with which he feels most comfortable, making an almost seamless transition at home between pronouns and names, from Claude to Poppy, son to daughter. But the transition for his brothers, his school, and the people in their orbit is not so seamless. After several parent-teacher and parent-administration discussions at school, the absurdity of the rules for a transgender child make themselves apparent: Wisconsin schools have accommodations for a trans student, but still somehow manage to insist that the gender binary be enforced. This is best illustrated in quotes from his teacher, Miss Appleton:

“Little boys do not wear dresses.

Little girls wear dresses. If you are a

little boy, you can’t wear a dress. If you are a little girl, you have to use the nurse’s bathroom.

***

“Meaning if he is a girl, he has gender dysphoria, and we will accommodate that. If he just wants to wear a dress, he is being disruptive and must wear

normal clothes.”

Meaning, in other words, that trans students must still check one box or the other, and adopt all the expected characteristics of the “selected” role of “male” or “female,” thus invalidating any character trait that might not conform to our static and polarized cultural gender norms. (Please note that I put the word “selected” in quotes on purpose.) One character comments,

“This is a medical issue, but mostly

it’s a cultural issue. It’s a social issue and an emotional issue and a family dynamic issue and a community issue.

Maybe we need to medically intervene so Poppy doesn’t grow a beard.

Or maybe the world needs to learn to love a person with a beard who goes by ‘she’ and wears a skirt.”

When Wisconsin proves to be hostile in several ways to the child Poppy is becoming, Rosie and Penn decide it’s time to go somewhere their child can find a greater degree of acceptance, and they move the entire family to Seattle, shaking up all their children’s lives in order to accommodate the needs of the youngest. For the eldest, Roo, this means leaving behind all those things that are precious to a high school teenager who has lived his entire life in one place with one group of friends. It has similar, though lesser, effects on the other three boys, who are divided between accepting the necessity of providing safety for Poppy while also believing it won’t make much difference. In this, they are perhaps more realistic than their parents. On the first day in their new house, Rosie and Penn reveal Poppy’s “secret” to their next-door neighbors (intending to be similarly honest with everyone in their new city), but the neighbors encourage them to allow Poppy to be a girl without revealing her past as a boy to anyone. This is how the entire family’s never intentional life of deception begins, and continues until Poppy is on the verge of puberty and the whole thing blows up in their faces.

I won’t say much more about the story, because I have already outlined the first half pretty thoroughly, and would like you to have a reading experience unfettered by expectations for the remainder of the book. I will say that I appreciated the author bringing in the situations of transgender individuals in more fluid societies, which is why I feature this painting at the end. If you read the book, which I hope you will do, you will understand its significance and inclusion.

Category: Coming of age, LGBTQ, Relationship Fiction, Socially engaged fictionTags: E-book, Stand-alone

Resolution

I just finished reading the last two books in Elly Griffiths’s Ruth Galloway mystery series: The Locked Room, and The Last Remains. For those who aren’t familiar, Ruth is (now) a 40-something archaeologist/professor at the University of North Norfolk, and lives in a cottage overlooking the Fens (marshlands) and the ocean. Norfolk was settled in pre-Roman times and then taken over by the Romans; during the Middle Ages it was a center for the wool trade, resulting in the building of many churches. Since it has remained a largely rural county, this makes the area a rich archaeological source of artifacts and, as Ruth discovers in her role as a forensic consultant to the police, bodies both ancient and modern.

I don’t want to get too spoiler-y in this post, but the arc of the books is partly professional and partly personal, and it is the personal for which all we fans and readers have been waiting resolution for many years and volumes. In her role as a consultant, Ruth is thrown into the company of Detective Chief Inspector (DCI) Harry Nelson, a married man with a couple of children, and an impulsive one-night stand results in a pregnancy for Ruth. She doesn’t ask for anything to change, knowing how deeply dug into married life is Nelson, and although she has doubts about her own abilities to raise a child effectively by herself, her love for her daughter, Kate, conquers all.

Kate is born at the end of book #2, and there are 13 books that follow after. In each one, the discovery of a body or bodies draws Ruth into the subsequent police investigations, regularly renewing questions about her relationship to Nelson. There are at least two books that constitute partial departures from proximity: In one, Ruth and Kate travel to Italy without Nelson, while in another they actually move away from Norfolk to Cambridge and in with a “boyfriend” of Ruth’s for a period of time. But if you are a long-term reader of this blog, you will perhaps remember how many times I have complained about the on-again, off-again nature of their interactions, the glacial slowness with which things have moved, and the constant wondering: Will they ever get together? Will Nelson get up the courage to leave his wife for Ruth? Will Ruth ever let her growing exasperation prompt her to kick Nelson to the curb for good? This speculation has overshadowed the mysteries in more than one book in this series and has caused me to swear off reading them on several occasions, but there’s something appealing about the awkward archaeologist that I have found hard to resist, and I have always come back to get caught up.

At last, however, that is at an end: Book #15 is the last in the series, and finally we have resolution to the decade-long question: Will they or won’t they? But first we have to participate in the perpetual angst throughout Book #14 and part of the last.

I’m not going to reveal anything else here, so let’s take a look at the mysteries detailed in these two books. As I have commented before, the books have seemed to alternate, throughout the series, between one that is compelling and one that phones it in, to the point where there were at least two books I recommended that readers skip, going instead to a synopsis to find out the details about the personal relationships while avoiding the somewhat boring plots. That has held true to the end; The Locked Room‘s mystery is both confusing and slight, while The Last Remains has a tight, interesting story line that includes several characters both new and old and nicely ties up some dangling questions by taking us back to the very first mystery on which Ruth and Nelson collaborated. The one thing that does distinguish The Locked Room is that Griffiths set it during the recent pandemic and imbued her story with all the inconveniences and tragedies we experienced during that time period, which was both refreshingly real and disturbingly uncomfortable, a reminder of all that we did and didn’t do and all that we lost.

I still struggle a bit with the idea that Ruth and Harry have taken 15 years to confront their feelings, but I congratulate Elly Griffiths on a largely successful and mostly involving mystery series. I hope with her Harbinder Kaur books that she draws us into many more murderous adventures.

Category: Mystery, Relationship Fiction, Socially engaged fictionTags: End of series, Police Procedural, Series

Literary fiction

As I get older, read more, and spend a lot of time and energy reviewing what I have read, I am beginning to realize that I am not, despite aspirations, a particularly sophisticated reader. Beyond that, I have recently concluded that I tend not to trust my own reactions when it comes to reading and reviewing books that are deemed “literary” by other critics and/or readers. My priority in my reading life has always been to find and experience good story, but when I am confronted with something that doesn’t feel that way to me, rather than judge the book as being lacking, I judge myself as a reader. I think I am going to aim to change that in future.

I have experienced this twice in the past six months, and the way I came to realize it was to read others’ extremely perceptive (and much more objective) reviews on Goodreads. I just finished reading Cutting for Stone, by Abraham Verghese, and at some point during its perusal I remarked that I found it nearly as hard going as Demon Copperhead, by Barbara Kingsolver. This observation should have revealed more to me than it did; but it took the remarks of “Ayaz,” on Goodreads, who gave the book a measly two stars (indicative of “it was okay”) to make my thoughts suddenly gel on the whole subject of literary fiction.

First, a description of the book: The protagonist, Marion, is a twin. He and his brother, Shiva, are the offspring of a brilliant but flawed British surgeon and his surgical assistant, a young and extremely devout Indian nun, whose pregnancy is only revealed to her colleagues (including the father) when she goes into labor. Their mother dies and, unable to cope with either the loss of Sister Mary Joseph Praise or the unexpected manifestation of offspring, their father abandons them; the twins are raised by a loving foster family made up of the remaining staff members (and their servants) of the mission hospital in Ethiopia in which they were born. Given the circumstances of their birth and that they are constantly exposed by their foster parents to both talk about and observation of medical procedures, it’s nearly inevitable that the two will grow up to become doctors, although the twins take entirely different paths towards this end. Personal conflicts and political events serve to separate the twins for an extended period, until tragedy reunites them.

I always have high hopes at the beginning of a book that has come recommended for its voice, its story, and/or the quality of its writing. Sometimes, as with Demon Copperhead, I recognize those merits for myself, while nonetheless being somewhat dragged down by both the intensity and longevity. But sometimes, as with Cutting for Stone, I struggle to recognize the merit as I grapple with the completion of the reading.

I’m not saying this is a bad book; although I breathed a small sigh of relief and reduced my rating from five stars to three after coming to certain realizations about my reaction to the book, I still found much to admire. But there were also unacknowledged problems with its narrative that I didn’t trust myself to articulate but that I could plainly see when someone else pointed them out for me.

One observation that resonated was a problem with a sustained development of the characters. When I reviewed Demon Copperhead, I noted that even though the book took me more than a month to read—having put it down for extended intervals to peruse more light-hearted works—I never lost sight of who the characters were, because their portrayal was so strong. With Verghese’s book I came to recognize that part of my frustration that caused me to drag out its completion was that there were certain key characters about whom I wanted to know more, but the author’s promising start in developing them was, over and over again, truncated or abandoned in favor of a sensationalistic denouement in the story as it transitioned from one stage to the next. His female characters are particularly clichéd, but even the men sometimes become indistinguishable one from another because of the similarity of their language, sentiments, and presentation. There were a couple of characters who stood out, but for the most part they were all subsumed by their careers.

Although Verghese is himself a medical doctor, I discovered that having that expertise and perspective were not enough for his descriptions to transport me into the lives of his characters. There were certain compelling moments in the throes of a complex operation that were exciting and involving, but the rest of it felt both clinical and too educational, for want of a better word, for a novel.

The purpose of this book was clearly to illustrate the depth and breadth of the idea of family amongst people who are unrelated but bonded, and although that was, to an extent, achieved, I grew first exasperated with and then bored by Marion’s viewpoint. And although this is ultimately a coming-of-age story like Demon Copperfield, I never perceived from Marion the same quality of voice that carried us from childhood to manhood. There was a certain sameness about the narration that caused it to be more tedious than it should have been.

The part I think I enjoyed most, and where I felt Verghese shone, was in the presentation of Ethiopia as a country and culture, caught up in the politics of change that were sweeping that nation in the upheaval of multiple revolutions. The world-building felt fresh and genuine.

Because of my realization about the sometimes excessive reverence I have for literary fiction, I will freely admit that I may have gone too far the other direction in judging this book. Certainly there are many readers out there who find its language, characters, and story completely compelling and who have freely awarded it top marks. If you still have a desire, after my comments, to read it for yourself, then by all means do so. We are all gripped differently by our reading, and you may agree with many that this is a masterpiece. But as for me, I’m going to try, in future, to tune in better to my innate sense of the quality of the story itself, which is my ultimate criteria, and let that lead me when evaluating any book, literary or otherwise.

Category: Coming of age, Literary Fiction, Socially engaged fictionTags: Appeals, E-book, Stand-alone

A book about books

If you, like me, enjoy reading books featuring a bookstore, a library, an author, or, in this case, a bookbinder, you might enjoy the one I just finished—The Echo of Old Books, by Barbara Davis. I last encountered Davis as the author of The Keeper of Happy Endings, which featured another of my passions (Paris), and although that one wasn’t a favorite, it was well written enough that I was willing to give another book of hers a try, particularly given the theme.

Ashlyn Greer is a dealer in rare books, whose small, eclectic New Hampshire shop sits in the front room of her real income-generating activity, the restoration of old or damaged volumes. In addition to doing custom work by request, Ashlyn is constantly on the lookout for some rare find in a remainders box at the local library or thrift shop that she can restore and sell. Ashlyn has a secret gift whose scientific name is psychometry…

the ability to discover facts about an event or person by touching inanimate objects associated with them.”

In Ashlyn’s case, this extrasensory perception is limited to books. She can feel an echo of the owner or reader of the book, if their emotions were strong enough while the book was in their possession.

One day Ashlyn lucks into a find of two beautifully bound books that present something of a mystery: There are no authors listed, nor publishers nor dates, and the books are apparently the story of a doomed romance told from either side, one by the woman, the other by the man involved, each addressing the other in the first person as if writing a long letter. Ashlyn is intrigued by what purpose these books could have served, and overwhelmed by the raw emotion she feels pulsating from both of them.

She starts to investigate the mystery, first by reading the books and then by attempting to find out where they came from before she found them in a box of otherwise worthless donations at her friend Kevin’s store. The dual story takes her back four decades (The Echo of Old Books is set in 1984, and the books in the story were written in 1941) to a love affair between unequal partners—a pampered heiress and a footloose newspaperman—and also leads her to a descendent of one of these lovers, in the course of her quest to get more information.

I really liked the way the book was laid out—the scene-setting in 1984, followed by alternating chapters of the two mystery books and then a new chapter with Ashlyn’s reaction to what she has read. There are powerful themes expressed in the two old books: They explore the growing anti-Semitism amongst some wealthy and influential Americans in the ramp-up to World War II, and also comment extensively on the roles of affluent women, who seemingly had it all but were in fact marriageable chess pieces used by their fathers to capture more wealth and power.

The book was a little long, and the beginning was drawn out to the point where I almost lost interest, but that interest was renewed by some book-binding details and the introduction of an intriguing new character, and I’m glad I kept reading this story about tragic endings and second chances. I will happily add it to my Goodreads list of “books about books.”

Category: Historical, Relationship Fiction, Socially engaged fictionTags: Books about books, E-book, Stand-alone

Re-wilding

Scottish-American conservationist John Muir, the “Father of the National Parks,” once wrote that

“…when we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else.”

John Muir

This quote was specifically called into use when considering the failing ecosystem of Yellowstone National Park, where the purposeful removal of wolves, Yellowstone’s top predator, meant that the elk population overgrazed the plants and trees, leading to the demise of songbirds, beavers, and cold-water fish. Wolves were the missing link in the equation that would keep Yellowstone healthy and, 28 years after they were reintroduced (in 1995), the ripple effect is considered one of the most successful rewilding efforts ever undertaken. The culling of the elk herds by the 80+ wolves now living in Yellowstone benefitted ravens, eagles, magpies, coyotes, and bears. Wolves’ preying on coyotes increased the populations of rabbits and mice, providing a wider food source for hawks, weasels, foxes, and badgers. Muir’s quote was certainly prescient.

Charlotte McConaghy’s novel Once There Were Wolves posits a similar experiment to bring wolves back to the forests and Highlands of Scotland to rebalance biodiversity, depicting the difficulties inherent in convincing the resident human population (primarily sheep farmers) of the benefits to be had, and protecting the wolves against the farmers’ and ranchers’ conviction that humans and wolves can’t

co-exist on the land.

The protagonist is lead biologist Inti Flynn, a passionate young woman whose unusual upbringing by her father—living a subsistence life deep in the forests of Canada—has shaped both her beliefs and her career. She arrives in Scotland accompanied by her twin, Aggie, who is deeply damaged, mostly silent and passive, and spends all her time sequestered in their cabin. Inti has an extraordinary affinity for the wolves, heightened by an actual neurological condition called mirror-touch synesthesia:

“My brain re-creates the sensory experiences of living creatures, of all people and even sometimes animals; if I see it I feel it, and for just a moment I am them, we are one and their pain or pleasure is my own. It can seem like magic, but really it’s not so far removed from how other brains behave: the physiological response to witnessing someone’s pain is a cringe, a recoil, a wince. We are hardwired for empathy.”

Inti Flynn, Once There Were Wolves, by Charlotte McConaghy

The book is part literary fiction, part mystery, and engrossing in its narrative. Although the rewilding program is officially sanctioned by the government, there is massive resistance by the locals, some of whom are aggressive with their threats to kill wolves who set foot on “their” land. Inti struggles between her desire to protect her wolves and her need to engage with the locals as something other than a know-it-all outsider. She is assisted in making the human connections by the sheriff, local-boy Duncan MacTavish, but he remains something of an enigma throughout the story, and his passivity when it comes to enforcing Inti’s cause frustrates her. Then a local farmer goes missing, and speculation inevitably turns to assumptions about wolf culpability.

The best parts of the book are Inti’s detailed observations about the wolves—how they relate to one another and to their surroundings, and their habits, travels, and behaviors as they integrate into this foreign environment. The reader is transported to the hillside blind where Inti watches a new batch of pups scramble and play just outside the mouth of their den while the adults warily sniff the air, cognizant of the human close by, and the welfare of the small packs dispersed around the town becomes personal as each wolf becomes familiar.

Less effective, for me, was the rest of the narrative, especially that surrounding the sheriff, Duncan, and Inti’s sister, Aggie. I felt like we were too far into the story before we understood what happened to destroy Aggie’s confidence and turn her into the near-catatonic figure she now presents. Likewise, Duncan runs hot and cold, both with Inti and also with his commitment to doing his job (although his devotion to the individuals in his community is touching), and I was frustrated by the incitement to waffle over whether he was a good guy or a bad one. But McConaghy knows how to keep the action flowing throughout the narrative, and the mystery remains intriguing up to its final solution. Readers should be aware that this book presents scenes including violence and abuse, although much of that action takes place “off screen,” or is implied but not graphically described. But the few graphic depictions are powerful and potentially disturbing.

I enjoy a story with some meat on its bones—focusing on a particular iteration of a wider philosophy. As happens with my reading choices from time to time, there was a serendipity of theme between this book and The Crow Trap, by Ann Cleeves, which also detailed a biodiversity study in a rural area, but whereas I found that book almost completely lacking in appeal, Once There Were Wolves delivers all kinds of intellectual and empathetic content. Despite the few caveats above, I would definitely recommend this book to anyone interested in both a gripping story and a thorough education about how the biological world works.

For more information about the Yellowstone rewilding project:

https://www.muchbetteradventures.com/magazine/yellowstone-wolves-rewilding-1995-history-books/

Category: Literary Fiction, Mystery, Socially engaged fictionTags: Appeals, E-book, Stand-alone

Metaphor

If I had to define the central theme of the book Black Cake, by Charmaine Wilkerson, it would probably be summed up by this quote:

“But the fact was, when you lived a life, under any name, that life became entwined with others. You left a trail of potential consequences. You were never just you, and you owed it to the people you cared about to remember that.”

ELEANOR BENNETT

The cake in the title, made with blended fruits soaked in liquor and with burnt sugar added to produce its distinctive black color, is a symbol of family, tradition, a thread of familiarity that stretches back to connect all the disparate parts down through generations. It’s also a metaphor for the complexities of culture, in which such issues as colonization, slavery, immigration, assimilation, and social, racial, and political borders figure into every aspect of life—or a recipe.

This book is a kind of revelatory fiction; the story is told completely in third person, but from multiple voices and points of view, and a new bit of the story is revealed as another person takes up the narrative and adds his or her perspective. Situations are fleshed out by hearing about them from different voices and seeing them through different eyes, and each narrator has a reaction to share. Although Eleanor Bennett, the matriarch of this family, is the pivotal character, the story is moved forward by noting the effects all the secrets of her life have had on the members of her family, most specifically her children, and also by revealing the major impact that both significant and tertiary characters in her past have had on hers and everyone else’s future.

Although I had some difficulties with the book, the most persistent probably being that Wilkerson stuffed it as full of social issues as her black cake bulges with fruit, I appreciated it as a whole. I couldn’t wait, when I reached the end of a chapter, to turn the page and see what the next one would contain, and I was seldom disappointed. Murder, desperate acts, rebirths, aliases, grand secrets, it’s all there in Black Cake. The story is about decisions made that can never be taken back, about necessary sacrifice and stubborn persistence. It’s a powerful picture of what it means to be a survivor, and to preserve a sense of racial and cultural identity throughout. The thing I liked most about it was that the narrative evolved as a true storyteller would reveal it, carrying you along with her into an evocative past. Give it a taste and see if it’s to your liking.

Category: Literary Fiction, Realistic Fiction, Socially engaged fictionTags: E-book, Stand-alone

Subversive, epic

This week when my Kindle ran out of juice and I wanted something to read before bed, I impulsively picked up a book I have read several times before (although it inexplicably remained uncatalogued on Goodreads): The Terrorists of Irustan, by Louise Marley. I have mentioned it at least twice before on this blog, but after reading it for, I think, the fourth time, I wanted to give it a space of its own, because I think it’s that important.

This book is hard to classify. It is science fiction, set as it is on a planet distant from Earth, colonized for the purposes of mining a precious material (rhodium) that is sold back to the industries on the parent planet; it is also powerfully dystopian; and it is definitely a feminist manifesto.

Lest any of those put you off from reading it, it is also a grippingly told story with powerful scene-setting and characters you won’t easily forget. If none of those themes sounds appealing to you, read it for the story!

The book takes place in the future on a planet that was settled by humans long ago, but the society on Irustan is ruled by the Second Book of the Prophet, and mirrors (and expands upon) the claustrophobic (especially for women) religions of middle eastern countries today. Everything is governed according to this restrictive religion, and as long as the rhodium keeps coming, Earth’s Port Authority on the planet refuses to intervene.

On Irustan, the men dominate every aspect of the culture, while the women remain virtually invisible: They do not appear outside the home without being wrapped head to foot in veils, and may not communicate directly with any man save their husband and the servants of their household, nor be seen by them. They may not own property, drive, or use a wave-phone. Their husbands have complete control over their destinies and those of their children. The highlight of their lives is “Doma Day,” once a week when the husbands all go to the temple and the wives and children are allowed to gather at the homes of their close friends to socialize, trade gossip, and share a meal.

The main character is Zahra IbSada, one of the women on the planet with a tiny portion of independence. In this world of male dominance, there is a strong taboo against even the acknowledgment by men of illness or infirmity, so any kind of medical treatment has to fall to a small group of women (fewer than 100 for the entire population of the planet) who are trained as “medicants.” They are a somewhat poor excuse for doctors, because their training is severely restricted, but they are aided by amazing medical technology from Earth, where machines have been developed that can diagnose illness and provide remedies directly into the bloodstream. The medicants are instructed in the use of these machines and most go no farther in their development as doctors.

Zahra is one such medicant, with better training than most due to the woman with whom she apprenticed, and also because of her own insatiable appetite for medical knowledge. The medicants treat the colonists injured in the rhodium mines, dosing them regularly with a drug therapy that prevents them from contracting a deadly prion disease from inhaling the dust, and also minister to any others who are sick or injured. This gives them an extraordinary knowledge of the private lives of those on their clinic list, and ultimately provokes Zahra to make a controversial personal decision in the course of her duties that will have unexpectedly wide ramifications.

Zahra is aided in this course of action by a Port Authority employee, a longshoreman who is in charge of delivering the medical supplies shipped from Earth to the various women’s clinics. Jing-Li comes from the ghettos of Hong Kong and used a job working for Port Authority as a way to leave Earth without having to go to college or obtain a career that would qualify a person for interplanetary travel, an option that was unavailable to someone from Jing-Li’s social class. The collaboration between the two is slight but powerful, and their fates end up being intertwined as Zahra seeks a way to change the oppressive social structures of her world.

Somewhere in The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood comments about how extremist Eastern religions are not that different from extremist Western religions; The Terrorists of Irustan is Louise Marley’s example of a faux Middle Eastern counterpart to Atwood’s book, and I believe should be read with the same attention given to that classic. (And yes, it would make an amazing series as well!)

Category: Dystopian, Science Fiction, Socially engaged fiction