Not thrilled

I have read all of B. A. Paris’s books, most of which would be considered either suspense or thriller. Many writers (and publishers) and many readers’ advisors can’t tell you the difference between a mystery, a suspense novel, and a thriller. After reading exhaustive discussions and dissections, here are the differences at which I have arrived.

First of all, neither a suspense nor a thriller is about solving a crime, they are about stopping a killer or a crime. So they are not necessarily a whodunit as is a mystery; we may know who the villain is from page one.

In a thriller, the protagonist is in danger from the outset, and action is a required element. Pacing is the key ingredient. In suspense, danger is more important than action, and the protagonist becomes aware of danger only gradually. “Suspense is the state of waiting for something to happen,” said Alfred Hitchcock. Setting and mood are key. There must be terror, confusion, upset, and conflict.

A thriller has to start off with a bang, and have a clearly defined hero and villain, because the thriller is all about the push and pull between the two. By contrast, the only real requirement of a suspense story is that it build, and that it keep the reader on edge with a series of reveals or surprises until the final one. Suspense can be present in any genre; a suspense novel is simply one where the reader is uncertain about the outcome. It’s not so much about what is happening as what may happen. It’s about anticipation.

Given those definitions, I would term most of Paris’s books as suspense, although I have seen them referred to (and have done myself) as thrillers. She is great at building her narrative from seemingly innocuous to a crazy amount of tension. Perhaps her best example of this is Behind Closed Doors, in which you know, almost from the first page, that there is something wrong, but have no clue just how much there is to uncover until the story really begins to ramp up.

When I bought my copy of The Dilemma, therefore, it was with a great deal of anticipation that it would give me a likewise breathless interval. Unfortunately, I failed to achieve “that willing suspension of disbelief” (touted by the poet Coleridge) about some of the key facts present in this book upon which the story depends.

The basic premise is that Livia and Adam, married for 22 years, each has a secret he or she wishes to tell the other, but can’t quite bring themselves to do so because of the circumstance in which they find themselves. But it is that circumstance that sets up, for me, the biggest roadblock in this story.

Livia and Adam met when Livia was 17 and Adam was 19; Livia became pregnant, and was summarily rejected by her parents even though she and Adam married promptly, before baby Josh was born. Four years later, they added daughter Marnie to their family. The couple are happy in their marriage, pleased with the way their children have turned out, and possessors of many good friends, the most prevalent of whom are two other married couples about their age, and these people’s children.

Because of the dual facts of Livia’s pregnancy and the rejection of her by her parents, the two had a hurried civil service and were deprived of the big formal wedding about which Livia had always dreamed. This has apparently preyed upon Livia’s mind over the years to the point where she has saved up her money since she was 20 years old in anticipation of a huge and elaborate celebration for her 40th birthday. The story itself takes place during the 18 hours or so surrounding that celebration. And the birthday bash is the vehicle used to delay the confiding of devastating facts between the spouses.

This is the one big place where the story lost me. If you have that much regret about missing out on your wedding, why not stage another wedding? People renew their vows all the time and use that occasion to have things just as they would have wanted them on their big day. At one point Livia even comments that if she had waited an additional couple of years, the party could have been for hers and Adam’s 25th wedding anniversary, but no; she is determined to do it for her 40th birthday. This seemed to me to be so self-regarding as to constitute a problem; but apparently Adam is fine with it.

If a renewal of vows or a big anniversary are off the table and you’re so determined to make it all about yourself, why wait? Why not have the party at age 30? Why be so focused, for literally two decades, on one particular birthday? The story details at length how every time she went shopping and saw a fabulous dress, she mentally tried it on as a possibility for her big day. I just didn’t buy it that a person could be so self-obsessed with celebrating a particular birthday that they planned it over that extended period of life.

So, on to the secrets. Livia’s secret involves her daughter Marnie, 19, who is doing a year abroad through her college, and has been in Hong Kong for most of the past year. It turns out her finals are during the same week as Livia’s party, so she has told her mother she won’t be able to make it. Because of this big secret, which Livia has not discussed with anyone because she first wants to confront Marnie, she is somewhat guiltily relieved that her daughter won’t be coming home yet. She doesn’t want to divide her focus between the party and managing the fallout from the revelation amongst several people in their social circle. But Livia feels guilty for not having shared this information with Adam.

Meanwhile, Adam and Marnie between them have planned a surprise for Livia’s party, but events don’t go as planned and suddenly, Adam is overtaken by news that, if he shares it immediately, will ruin Livia’s big event. He is left to reason that as long as he doesn’t know the facts for sure, no one can fault him for not speaking up; but he knows that if and when Livia discovers how long he held this news back from her, she will be legitimately enraged. So Adam and Livia both spend the hours of the party keeping secrets from one another that they know will inevitably be revealed as soon as the party is over, and this dread (especially for Adam) overshadows what should have been a joyous occasion.

That’s it. That’s the story. That’s the source of suspense. And the machinations to which the author resorts in order to enable Adam and Livia to keep their secrets from one another are just ridiculous. Yes, by the definition I spelled out earlier, this does qualify as suspense for much of the story, although I couldn’t say that I remained uncertain about the outcome. But the vehicle here is a family drama that could have been adequately dealt with in a succinct and much more engaging short story, not dragged out for 342 pages of angst.

I’m not going to say, like some other reviewers on Goodreads, that I’m done with Paris and won’t read any more of her books; but if you liked the others of hers that you have read, my suggestion would be to skip this one and hope that she delivers a real page-turner next time.

Surprise heir

Ruth Ware’s novel The Death of Mrs. Westaway incorporates several things I love, and I was drawn to it from the first page. The protagonist, Hal (Harriet) Westaway, is such a vibrant character and her precarious existence is so appealing that it’s hard not to buy in.

Hal has been raised by a single mother in a small but unusual and fulfilling life; her mother was a tarot card reader in a booth on the pier in Brighton Beach and, partly through instruction and partly through absorbing the daily atmosphere of her mother’s tradecraft, Hal has acquired all the skills to follow after her when she is tragically killed by a hit-and-run driver right outside their front door.

Hal stays in their small but known and comforting bed-sit after her mother is gone, and takes up the mantle of tarot card reader, although she always hearkens to her mother’s voice in her ear that tells her not to believe the patter that makes her so successful with her clients. Hal enjoys the combination of the beauty of the tarot and the skillful use of psychological clues to direct the faith of the tourists and drunken hen parties in her “fortunes”; she doesn’t care for those few fanatics who return again and again trying to come at truths that Hal knows better than to promise them.

Hal has made one foolish decision in the aftermath of her mother’s death; between the halting start-up of her takeover of the tarot booth and the slow months of winter that don’t contain the huge number of customers present during the tourist season, Harriet got behind on her bills and resorted to visiting a moneylender. She is stunned to realize how quickly and disastrously the interest on this loan has compounded, and is in imminent danger from the loan shark’s enforcers if she doesn’t come up with the money soon.

Just at the crux of this fraught situation, Hal receives a letter from a law firm, telling her that her grandmother, Hester Westaway, has died and that her presence is required at the funeral and subsequent reading of the will. She knows just enough about her mother’s family to realize that someone has made a mistake; but there are sufficient similarities in her background that cause her to grasp at the idea that she can pull off a deception and perhaps come into some funds that will help her out of her desperate straits. She scrapes together the last of her funds, buys a ticket to Porthleven, and sets out to collect “her” inheritance.

Haven’t we all imagined at some point that a long-lost legacy will arrive in the mail or via a phone call? That we will be pulled back at the last second from the brink of ruin by the generosity of a remote relative who turns out to have doted on us as a precocious three-year-old and has been generous in their bequest? I loved the entire set-up for this story, and Hal’s tentative but determined foray into a strange house filled with family that may or may not be hers.

The tale owes a lot to both Agatha Christie and Daphne du Maurier: First of all, it takes place in Cornwall, scene of the bulk of du Maurier’s storytelling, and the creepy housekeeper definitely gives off an obsessive Mrs. Danvers vibe. The house itself is a gothic nightmare straight out of Christie, of cold, dark, dust-filled rooms reverberating with an unhappy past, and the Westaway family, though cordial on the surface, has obviously been greatly affected (and not in a good way) by their upbringing. It’s no coincidence that Hal feels the greatest affinity for the sole in-law in the bunch!

I have to say that the strong-willed, smart, and likeable character of Hal largely carried this book for me. I loved her back story, her personality, her profession, and her daring. The rest of the characters were, by comparison, made of cardboard, and some were outright cliché. They were okay as a backdrop for Hal, but it would have been nice if the only glimpses into their story had gone farther than a few incomplete and unsatisfying diary entries. None of them is overtly friendly, no one voluntarily supplies family history, and despite being surrounded by all these people, Hal has to solve her mystery through a not always compelling combination of research and subterfuge.

The thing is, The Death of Mrs. Westaway is not exactly a mystery, although there are mysterious elements to solve; it’s not entirely suspense, although it’s suspenseful; and the resolution is a bit telegraphed and not as exciting as it could have been. At several points in the story, it seems like the book doesn’t know whether it’s trying to be gothic horror, an Agatha Christie-style whodunnit, or a psychological thriller. But if you focus on the story as being Hal’s alone, and simply let yourself enjoy the atmospheric vibes, it ends up being a satisfying read. The integration of the tarot into the story made it special for me, as I have always had a fascination with both the artwork and the infused meaning of those cards. This is the second Ruth Ware book I have read, and although the other one was better conceived and executed, I believe I prefer this one based simply on the appeal of character.

2020 Faves

I don’t know if anyone is dying for a reprise of my favorite books of 2020. Since I am such an eclectic reader, I don’t always read the new stuff, or the popular stuff. Sometimes I discover something popular three years after everyone else already read it, as I did The Hate U Give this past January (it was released in 2017). Sometimes I find things that no one else has read that are unbelievably good, and I feel vindicated by my weird reading patterns when I am able to share it on my blog. But mostly I just read whatever takes my fancy, whenever it comes up and from whatever source, and readers of the blog have to put up with it.

Anyway, I thought I would do a short summary here of my favorite reads for the year, and since they are somewhat evenly populated between Young Adult and Adult books, I will divvy them up

that way.

YOUNG ADULT DISCOVERIES

Fantasy dominated here, as it commonly does, both because fantasy is big in YA and because I am a big fantasy fan. I discovered a stand-alone and two duologies this year, which was a nice break from the usual trilogy and I think worked better for the authors as well (so often the middle book is weak and the last book is rushed in those cases).

The first was The Hazel Wood and The Night Country, by Melissa Albert, and although I characterized them as fantasy, they are truthfully much closer to fairy tale. I say that advisedly with the caveat that this is not the determinedly nice Disney fairy tale, but a real, slightly horrifying portal story to a place that you may not, in the end, wish to visit! Both the story and the language are fantastic, in all senses of the word.

The stand-alone was Spinning Silver, by Naomi Novik. The book borrows a couple of basic concepts from “Rumpelstiltskin,” turns them completely on their heads, and goes on with a story nothing like that mean little tale. There are actual faerie in this book, but they have more to do with the fey creatures of Celtic lore than with any prosaic fairy godmother. It is a beautifully complex, character-driven story about agency, empathy, self-determination, and family that held my attention from beginning to end.

The second duology was The Merciful Crow and The Faithless Hawk, by Margaret Owen, and these were true fantasy, with complex world-building (formal castes in society, each of which has its own magical properties), and a protagonist from the bottom-most caste. It’s a compelling adventure featuring good against evil, hunters and hunted, choices, chance, and character. Don’t let the fact that it’s billed as YA stop you from reading it—anyone who likes a good saga should do so!

I also discovered a bunch of YA mainstream/realistic fiction written by an author I previously knew only for her fantasy. Brigid Kemmerer has published three books based on the fairy tale “Beauty and the Beast” (and they are well done), but the books of hers I fell for this year were about typical teenagers with problems that needed to be solved and love lives that needed to be resolved. My favorite of the four was Letters to the Lost, but I also greatly enjoyed More Than We Can Tell, Thicker Than Water, and Call it What You Want.

These were my five-star Young Adult books for 2020.

ADULT FICTION

As YA selections were dominated by a particular genre, so were my books in Adult fiction, almost all of them falling in the mystery section. But before I give you that list, I will finish up with fairy tale by lauding an original adult story that engaged me from the first page and has stuck with me all year: Once Upon A River, by Diane Setterfield. The fairy tale quality is palpable but the archetypal nature of fairy tales doesn’t dominate the story, which is individual and unique. It is the story of three children and the impact of their disappearances (and possible reappearance) on the people close to them, as well as on the inhabitants of one small town beside the river Thames who are caught up by chance in the events that restore a child to life. But the story encompasses more than her fate: It gives extraordinary insight into the issues of life and death—how much they are worth, how they arrive, how they depart, and what is the best way to pursue them.

Another book I encountered in 2020 that didn’t fall into the mystery genre or belong to a series was the fascinating She Rides Shotgun, by Jordan Harper. This was a short, powerful book by a first-time author, a coming of age story set down in the middle of a dark thriller that bowled me over with its contradictory combination of evil deeds and poignant moments.

And the last stand-alone mainstream fiction novel I enjoyed enough to bestow five stars was Just Life, by Neil Abramson. The story showcases the eternal battle between fear and compassion, and involves a deadly virus and a dog shelter in a fast-paced, gripping narrative that takes over the lives of four people. It made me cry, three times.

Most of the mysteries I enjoyed this year came from a “stable” of staple authors I have developed over the decades and upon whom I rely for at least one good read per year. The first is Louise Penny, whose offering All the Devils Are Here in the ongoing Armand Gamache series is nuanced, perplexing, and utterly enjoyable, all the more so for being extracted from the usual Three Pines venue and transported to the magical city of Paris.

Sharon J. Bolton is a reliable source of both mystery and suspense, and she didn’t disappoint with The Split, a quirky story that takes place over the course of six weeks, in stuffy Cambridge, England, and remote Antarctica. Its main character, a glaciologist (she studies glaciers, and yes, it’s a thing) is in peril, and will go to the ends of the earth to escape it…but so, too, will her stalker, it seems. The Split is a twisty thriller abounding in misdirection, and definitely lives up to Bolton’s previous offerings.

Troubled Blood, by “Robert Galbraith,” aka J. K. Rowling, is my most recent favorite read, and is #5 in that author’s series about London private detective Cormoran Strike and his business partner, Robin Ellacott. It’s a police procedural with a lot of detail in service of both the mystery and the protagonists’ private lives, it’s 944 pages long, and I enjoyed every page.

Finally, this year i discovered two series that are new to me, completely different from one another but equally enjoyable.

The first is the Detective Constable Cat Kinsella series by Caz Frear, which currently encompasses three books. I read the first two earlier in the year and promptly put in a reserve at the library on the third (which had yet to be published at the time), and Shed No Tears just hit my Kindle a couple of days ago. They remind me a bit of Tana French, although not with the plethora of detail, and a bit of the abovementioned Sharon Bolton’s mystery series starring Lacey Flint. Cat is a nicely conflicted police officer who comes from a dodgy background and has to work hard to keep her personal and professional lives from impinging one upon the other, particularly when details of a case threaten to overlap the two. I anticipate continuing with this series of novels as quickly as Frear can turn them out.

The second, which is a mash-up of several genres, is Charlaine Harris’s new offering starring the body-guard/assassin Gunnie Rose. I read the first two books—An Easy Death and A Longer Fall—this year, and am eagerly anticipating #3, coming sometime in 2021 but not soon enough. The best description I can make of this series is a dystopian alternate history mystery with magic. If this leads you to want to know more, read my review, here.

These are the adult books I awarded five stars during 2020.

I hope you have enjoyed this survey of my year’s worth of best books. I am always happy to hear from any of you, and would love to know what you found most compelling this year. I think we all did a little extra reading as a result of more isolation than usual, and what better than to share our bounty with others?

Please comment, here or on Facebook, at https://www.facebook.com/thebookadept. Thanks for following my blog this year.

Between the “greats”

I follow a lot of authors and anticipate their books and then, paradoxically, when they come out I take my time about getting around to reading them. I think it is a defense mechanism—equal parts fear that they won’t be as good as I have anticipated, or that they will be as good but that they will take me a lot of time and energy to get through and then think about and analyze. Sometimes, after all, you want a reading experience that is not intense, that is not taxing, that takes you somewhere familiar and allows you to follow along somewhat passively instead of being an active reader.

I have been in that exact place, during the past two weeks. I had a choice between reading Return of the Thief, “the thrilling, 20-years-in-the-making conclusion to the New York Times–bestselling Queen’s Thief series, by Megan Whalen Turner,” which is one of my favorite fantasy series of all time; Troubled Blood, the next in the exciting and engaging Cormoran Strike private detective series by alias J. K. Rowling; or V. E. Schwab’s brand-new book The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue, which is already making waves on all the best-of book lists out there. Thief and Addie are close to 500 pages apiece, while Rowling has done her usual of increasing the page-count of the book with each addition to the series, this one coming in at a whopping 944! So taking on any one of them won’t be a short-term experience, and deciding which to prefer above the others is also all locked up with my feelings towards each. Do I really want my favorite series to end?

Will these books live up to the others? Is the hype bigger than the book?

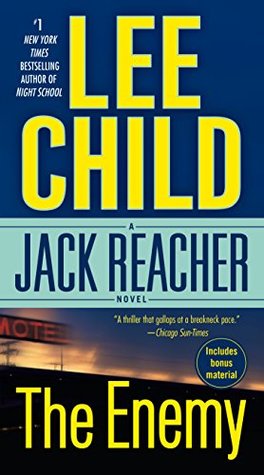

My response, this past week, was to turn aside from all three of them and pick up an early entry in Lee Child’s Jack Reacher series, The Enemy. After I got about a third of the way into it, some vaguely familiar scenes made me go check Goodreads, whence I discovered that I had actually read this book before; but it was more than five years ago, I have read at least 400 books (maybe more) in the intervening years and, despite certain scenes jiving with my memory, I didn’t remember anything about how it resolved.

As some readers of my blog will remember, I swore off of more Reacher books after reading the latest one, which was dark and ugly and didn’t feature the Reacher we had all come to know and respect for so many years and volumes. But this one is not only early in the series (#8), it’s also a flashback to when Reacher was still in the military working as an active police major (M.P.), solving crimes from within the confines of rules and protocol.

It begins on New Year’s Eve 1989, when Reacher is still in the army and has inexplicably been transferred from Panama to Fort Bird, North Carolina. Everyone else is out celebrating the turn of the decade, but Reacher is on duty when a two-star general is found dead in a sleazy motel 30 miles from the base, and it looks like he wasn’t alone. It’s the classic case of heart attack in the midst of sex but, by the time Reacher arrives, the hooker is no longer on the scene, nor is the general’s briefcase. Reacher’s new boss at Bird tells him to “contain the situation” so that the army won’t be embarrassed, but when Reacher goes to deliver the news of the general’s death to his widow in Virginia, the widow turns up dead too, and speculation about the contents of the briefcase suddenly turns the affair into something more complicated. Reacher recruits a (female) M.P. named Summer to help him run down all the details, and the two of them go ever deeper into danger as they defy the military to dig into this broadening potential scandal.

The book is a convoluted, intriguing puzzle from start to the very last page. There is a quote on the cover of my paperback from the Chicago Sun-Times that calls it “a thriller that gallops at a breakneck pace.” This proves that no one at that newspaper actually read the book; while it is, indeed, thrilling at certain points, and Reacher and Summer travel extensively across the States and into Europe during a 10-day period, spending as little as eight hours at some destinations, the pacing of this book is deliberate and every detail is noted, from what the protagonists are wearing down to how many cups of coffee they consume during breakfast at the Officers’ Club. In order to appreciate Reacher, you have to dwell in the details, because you never know when one will become significant.

This was a good one, and bravo to Lee Child for writing this background story so successfully.

As for making a decision between the three alternatives I mentioned at the top of this blog post, I think the safest is probably the stand-alone book in which I don’t have quite as much invested, so Addie LaRue will be my next read. Unless I put them all off to do some theme reading for the holidays, such as Jenny Colgan’s Christmas at the Cupcake Café? It’s entirely possible…

Bones will tell

I almost always feel sharply divided when reviewing one of Elly Griffiths’s Ruth Galloway books, because there is always much to like and also much to quibble about, and I sometimes feel nitpicky when I give in to the latter. And yet, that’s what a book reviewer does, if left feeling unsatisfied, irritated, or frustrated by a book. Her newest, The Lantern Men, is no exception to this split reaction.

The story in brief: Ruth has moved mountains in her personal life in order to distance herself from the father of her child, with whom she remains in love: She has moved away from her beloved Saltmarsh to Cambridge to take up a new job, she has moved herself and her daughter, Kate, in with her American lover, Frank, and she is no longer officially on call as Norfolk police’s consulting forensic archaeologist. That job she has left to her colleague, Phil, who has always craved the limelight that Ruth mostly shunned, and is quite thrilled with that position despite the inconvenience of having to pick up some of Ruth’s classes at the North Norfolk university since she has left.

It has been two years of escaping into these various refuges from her mostly inarticulate longing for DCI Harry Nelson, who does reciprocate Ruth’s feelings but who feels constrained to stay in his marriage, partly because of his respect and remaining affection for his wife and his desire to keep a good relationship with his two grown daughters, but mostly because of the surprise of a late-in-life child—George, who is now two years old. The fact that Nelson and Ruth share parentage of Kate continues to make their lives awkward, but everyone seems to have settled—if somewhat uneasily—into their place in this unorthodox extended family, with Nelson’s older daughters now embracing Kate as their sister and Kate, in turn, delighting in Baby George.

These are the circumstances when a convicted killer brings Ruth back into Nelson’s orbit. Ivor March is in prison for killing two women, whose bodies were found buried in his girlfriend’s garden and covered in his DNA; but Nelson has always been convinced that March was also responsible for the deaths of two other women, gone missing in the same time period and with an eerie similarity in both looks and circumstances to those he killed. Now March has offered to tell Nelson where the bodies are buried, but only if Ruth (rather than her colleague, Phil) will be the archaeologist who excavates the grave. He won’t give a reason, except to say that Ruth is a much superior archaeologist to Phil and will see things he wouldn’t.

As usual, the research into the legends behind the murders in this series is meticulously done; in this case, the legend of the Lantern Men, whose wandering lights on the Fen lure people to their deaths in the marsh, has been appropriated by three men who conceive of it as their duty or privilege to find people—specifically, tall blonde young women—lost on the marshes and rescue them. These men live, along with a couple of women with whom they are involved, at a retreat center for writers and artists and are themselves the instructors. The women they “save” end up staying with them for a time and then leave—or disappear, depending on perspective.

I had little fault to find with the cast of new characters whose intertwined relationships were so confusing to the police in terms of whose loyalty to suspect when it came to the murders. All of that was valid stuff for red herring material, and worked quite well. I also enjoyed, as per usual, the regular cast of officers and friends that surround both Ruth Galloway and Harry Nelson—officers Judy, Tanya, and Cloughie, and the eternally weird Cathbad—and the valid details of the police procedural.

What I did find poorly done was Ruth’s relationship with Frank. These two people have supposedly been living together for two years, and yet there is no closeness depicted. Ruth does remark at one point that she finds it endearing when Frank calls her “honey,” but the evidence, which is scant, about their interaction is that she holds him constantly at arm’s length, doesn’t confide in him about anything but the most surface of daily events, feels uneasy about depending on him too heavily when it comes to Kate, and basically seems almost blatantly uncomfortable with their situation. And Frank is such a cardboard character. We get one or two details about his American accent, the way he dresses, and how he helps around the house, and a few negative reactions when he discovers Ruth is seeing Nelson regularly again for work; but by and large Frank is barely a presence, let alone a major player, in this book.

I was hoping so hard that if something were to happen again between Nelson and Ruth, it would for once be something definitive—they would finally decide that, regardless of whom it would hurt, they would be together. But it was the same old thing, from a greater distance but otherwise identical, that we got in all the previous books: Ruth longs for a sign that Nelson still cares but feels guilty when he gives that to her, and ruminates on whether, if they were together, they could even stand to cohabit; Harry is even less articulate inside or outside of his mind, simply reacting with anger and jealousy at every manifestation of Ruth’s changed lifestyle and relationship with Frank. This has gotten so old that I am almost out of steam when it comes to hoping for a resolution. If it doesn’t happen in the next book, I’m out.

Apart from that big caveat, there were some small things in this book that just plain irritated me. One rule of writing: Never bring something up if it doesn’t have some kind of significance or result later on. In murder mysteries, of course, this means don’t show a gun early on if no one is going to use it later. But in this book it was more in small details that kept being dwelt upon but never explained. One example: Ivor March’s girlfriend, Chantal, is characterized as someone who always dresses inappropriately for every situation. The police drop by to see her at her home and she is attired as if she is on her way to a party, wearing a tight pink dress and heels, at 10:00 in the morning. At chance meetings she is wearing such outfits as a pencil skirt, white blouse and pumps, as if she is going to work, but she doesn’t (work). After three or four of these comments on her appearance, I expected that at some point someone would say, She dresses like this because…but no one ever does.

I also found the ultimate solution of the mystery to be rather flat, especially after all of the intricate hoopla. I don’t want to spoil anything, but there didn’t seem to be any more than a random motivation for the killer to do what the killer did…as if “I liked it” was sufficient justification. Maybe it is, in the case of a serial killer…but one would like to understand something about why a particular type of victim was chosen, or whether it was a peculiar synchronicity that put them in the killer’s path…something!

The cliffhanger at the end will probably carry me over to the next book, because I remain a sucker for finding out “what happened”…but if it doesn’t result in something more concrete, that will be the end for me of the saga of Ruth

and Harry.

Kate Racculia

In 2015, I picked up Bellweather Rhapsody, by Kate Racculia, to check it out for my high school book club. It had just won an Alex Award, which is given to 10 books each year that are written for adults but that have appeal for teens. My high school club had become sophisticated readers, and that year we were going almost exclusively for Alex Award books, since 18 out of our 23 members were seniors and the rest were juniors.

I never persuaded the club to choose the book; it always got high votes, but never made it to the final pick, and I always regretted that.

I never persuaded the club to choose the book; it always got high votes, but never made it to the final pick, and I always regretted that.

Recently, I was reminded of how much I liked it when I saw on the “What Should I Read Next?” Facebook page that Racculia had published a new book, Tuesday Mooney Talks to Ghosts, in 2019. I put it on reserve for my Kindle at the library and awaited its arrival.

While I waited, I went back to Goodreads to review what I had thought of that first book. A brief description: Every year the Bellweather Hotel in upstate New York hosts a high school musical competition called “Statewide,” where music and performance students gather to display their skills. In 1997, twin high school seniors Alice and Bertram “Rabbit” Hatmaker have both qualified to attend. Rabbit plays bassoon in the orchestra, while his sister, an aspiring actress and singer, is in the chorus. Meanwhile (unrelated to the competition), Minnie Graves, who was a child attending a wedding in 1982 when she discovered the groom shot dead and the bride hanging from the light fixture in room 712, has returned for the weekend with her support dog, Augie, to attempt to face down her demons.

Alice is paired as a roommate (in that same room, of course!) with flute prodigy Jill, who also happens to be the daughter of the hated and feared Viola Fabian, sarcastic head of Statewide. Alice discovers Jill’s hanging body in their room on the first evening, but while she runs to get help, the body disappears. Viola dismisses it as an attention-seeking prank, but…if so, where is Jill? All in attendance will have plenty of time to find out, as the Bellweather is enveloped by the biggest snowstorm of the season, and no one is able to leave.

This book started out feeling like a cliché, if an enjoyable one:

The set-up was like a combination of The Shining (Stephen King) and Christie’s And Then There Were None, and I had resigned myself to enjoying it for those familiarities, with perhaps a few modern twists. But there’s a whole lot more going on in this book than just a murder mystery. It’s a coming of age story, for both children and adults, compressed into a wild weekend in which the adults must re-examine what they’ve been told, what they’ve experienced, and what they remember longing for, and the children go through profound changes due to the catalysts provided by this weird music festival in a moldering old resort, while everyone (well, almost everyone—it is a murder mystery, after all!) comes out the other side changed. Parts are hilarious, parts are incredibly touching, and I loved the resolution for all the characters, who were sharp and quirky, and all of them unique.

Tuesday Mooney Talks to Ghosts has a lot of the same things going for it. Racculia’s real gift is for creating memorable characters and making you care what happens to them, and in this book it’s Tuesday, Dex, and Dorry (and well, maybe Archie).

Tuesday Mooney has an unconventional job: She is what’s called a prospect researcher, which means she profiles wealthy people (for a Boston hospital) to see who best for the office fundraisers to hit up for donations. She has the skills of a private detective, but goes beyond those to assess property, analyze gossip, and also rely on her finely honed instincts to find information and connections. She is uniquely suited to this work, being a loner who prefers to be on the outside, noticing what the insiders will miss. She is a guarded person, whose best friend of 10 years has never even been to her apartment. Her austere reserve rises from a genuine and justified fear of having her heart broken.

She is among a dozen employees who have volunteered to work at the hospital’s “Auction for Hope,” to staff the sign-in tables, keep track of auction bids, and make herself generally useful. Tuesday always volunteers, because after learning absolutely everything she can about her subjects, these events are her only opportunity to interact with them in person. But she’s no fan-girl: She simply wants to weigh her assessment of their facts and figures against the reality of a first impression.

At this particular event, Tuesday manages to finagle a place on the guest list for her best friend, Dex Howard, a gay financier who longed to be in musical theater but settled for a large paycheck. Dex looks around for someone interesting to sit with, and meets eccentric billionaire Vincent Pryce, a collector of Edgar Allan Poe memorabilia, and his much younger wife, Lila. In the course of the evening, Pryce is outbid, stands up dramatically as if to challenge the person doing the bidding, and drops dead of a stroke. The Boston Herald headline the next day read PRYCE BIDS FAREWELL.

But his death is not the big news: Pryce has created an epic treasure hunt throughout Boston—clues inspired by Edgar Allan Poe—whose winner will inherit a share of Pryce’s wealth. Tuesday’s curiosity combined with her skills lead her and her oddball crew—Dex, her teenage neighbor Dorry, and the handsome heir to the Arches fortune she met at the benefit—into a complicated game that will make them face past tragedies, present shortcomings, and future hopes.

As I initially underestimated Bellweather Rhapsody, so did I have lesser expectations for this book. First of all, both the title and the cover art strongly suggested a middle-school novel, especially since many reviewers were comparing it to that old chestnut The Westing Game, by Ellen Raskin. Although it was reminiscent, in some ways, of that book, the one it reminded me of more was The Extraordinary Education of Nicholas Benedict, the prequel to the Benedict Society series by Trenton Lee Stewart. I immediately thought of Tuesday as a more mature version of Nicholas—clever, introverted, and innovative. Her selection of her friends was likewise unexpected but key.

The supernatural element doesn’t actually merit the implications of the name of the book: Tuesday talks to only one ghost, that of her dead teenage friend Abby, and it’s a toss-up whether this is a real spirit contact or just a trauma reaction to her loss. (Her young friend Dorry longs to talk to ghosts, notably that of her deceased mother, and covets Pryce’s possession of Edgar Allan Poe’s goggles, said to allow one to see them.) But the plot is engaging, not just because of the mystery or the potential for ghosts but also as a result of what pursuing the treasure hunt reveals in each of the four main characters. The book shows what it’s like to be haunted, not by a spirit but by longings to express the person you have squashed down inside of you in the interests of practicality. It deals with the ethics, pleasures, and responsibilities of money, and what it’s like to have it/not have it. It enters in depth into the theme of friendship. It’s a great mix of mystery, introspection, campy humor, and cultural references that shouldn’t work but does. I couldn’t put it down.

I see from Goodreads that Racculia wrote another book, her debut, back before Bellweather. It’s on my list.

Appeals: Eccentric, captivating, substantial characters; evocative world-building with some attention to detail (in both cases); a nice genre mix of mystery, ghosts, and human drama; and an engaging writing style.

Laudable series

As I mentioned in my previous post, I recently spent some time re-reading the four books and two novellas Sharon Bolton wrote about Detective Constable Lacey Flint, who works for the London police, sometimes with a murder team, other times undercover and, in one book, as part of the River Police who patrol the Thames.

Lacey is an iconoclast, part of that subgenre of mystery characters known as loners. She attempts to be colorless and matter-of-fact, to keep her head down and fit into the team; but she has so many secrets of her own to keep that it’s a relief to be able to focus instead on the secrets of others, on the methods and madnesses of the serial killers she hunts. As a young, new, and inexperienced detective, Lacey is extraordinarily unlucky about attracting the attention of these criminals to herself. There is some sort of affinity between Lacey and her prey that causes some among her fellow officers to be over-whelmed by the suspicion that she herself is the criminal they are seeking.

In the first book, Now You See Me, Lacey serves as a source for “her” team on the history of the Jack the Ripper killer, whose scenarios, methods, and exploits the murderer they are now seeking seems to be mimicking. What becomes clear as the team follows this killer further into the labyrinthine twists and turns of serial murder, however, is that the Ripper similarities are camouflage for something much more sinister, and that Lacey is at the center of the story. The rarity of this and the other books in the Lacey Flint series is that the mystery keeps unfolding in each, all the way to the last page.

In the first book, Now You See Me, Lacey serves as a source for “her” team on the history of the Jack the Ripper killer, whose scenarios, methods, and exploits the murderer they are now seeking seems to be mimicking. What becomes clear as the team follows this killer further into the labyrinthine twists and turns of serial murder, however, is that the Ripper similarities are camouflage for something much more sinister, and that Lacey is at the center of the story. The rarity of this and the other books in the Lacey Flint series is that the mystery keeps unfolding in each, all the way to the last page.

In Dead Scared, Lacey’s sometime mentor and reluctant crush, Detective Inspector Mark Joesbury, asks her to go undercover as a student at Cambridge University to explore the inexplicable uptick of bizarre suicides on that campus. Given her fragility since the recent end of their last case, her boss, Dana Tulloch, and other members of the team are concerned that Lacey will be overwhelmed by the necessity of playing this vulnerable part. But Joesbury thinks she’s up to it, and she’s the obvious choice, given her youthful appearance, so she immerses herself in campus life and tries to discover more about the raft of lonely and insecure students who chose such unconventional methods of death. It’s an insane plot, fascinating (and misleading) to the last page, and full of peril for more than just Lacey.

In Dead Scared, Lacey’s sometime mentor and reluctant crush, Detective Inspector Mark Joesbury, asks her to go undercover as a student at Cambridge University to explore the inexplicable uptick of bizarre suicides on that campus. Given her fragility since the recent end of their last case, her boss, Dana Tulloch, and other members of the team are concerned that Lacey will be overwhelmed by the necessity of playing this vulnerable part. But Joesbury thinks she’s up to it, and she’s the obvious choice, given her youthful appearance, so she immerses herself in campus life and tries to discover more about the raft of lonely and insecure students who chose such unconventional methods of death. It’s an insane plot, fascinating (and misleading) to the last page, and full of peril for more than just Lacey.

In Like This, For Ever, titled Lost in the United States, Lacey is on leave from her job, and considering not returning to it. She hasn’t been able to process the jumble in her head created by her last case, and is spending most of her time obsessively working out and taking long late-night walks to exhaust her enough for sleep. I can’t say too much about the plot of this one, because it takes an unusual twist at about 85 percent that I don’t want to reveal, but it’s written with Bolton’s usual skill and panache. Because Lacey is on leave, she is not directly involved in most of the police investigation of a serial killer who is targeting young boys. But the usual crowd (Stenning, Anderson, Mizon, Tulloch, Joesbury) are all on hand, and Lacey inevitably gets drawn in by an unexpected personal involvement with a seemingly peripheral character, the boy next door. There’s lots of suspense, with multiple red herrings and a great resolution.

In Like This, For Ever, titled Lost in the United States, Lacey is on leave from her job, and considering not returning to it. She hasn’t been able to process the jumble in her head created by her last case, and is spending most of her time obsessively working out and taking long late-night walks to exhaust her enough for sleep. I can’t say too much about the plot of this one, because it takes an unusual twist at about 85 percent that I don’t want to reveal, but it’s written with Bolton’s usual skill and panache. Because Lacey is on leave, she is not directly involved in most of the police investigation of a serial killer who is targeting young boys. But the usual crowd (Stenning, Anderson, Mizon, Tulloch, Joesbury) are all on hand, and Lacey inevitably gets drawn in by an unexpected personal involvement with a seemingly peripheral character, the boy next door. There’s lots of suspense, with multiple red herrings and a great resolution.

A Dark and Twisted Tide once again involves Lacey Flint in spite of herself. After her leave of absence, instead of working as a detective she has gone back to uniform as part of the river police, hoping to return gradually to the force, but quiet time is not in the cards. Only Lacey could be out swimming at high tide in the Thames River (a hobby she has taken up since moving onto a houseboat) and discover a body floating in the river wrapped carefully in white burial cloths. Soon it becomes obvious that she didn’t find it by accident, that once again someone is focused on her, trying to draw her in. Being Lacey, she lets herself be drawn. This one, I have to say, was a little weird in spots even for me—but I enjoyed it. I had two problems: First, I think it’s time for Bolton to take up a new story line with regard to Lacey—not every case can relate specifically to her! Second, the long-drawn-out non-courtship of Lacey and Detective Mark Joesbury can’t be prolonged beyond a point, and I think we just hit that barrier as readers. To quote my British friends, at least give us a little snogging!

A Dark and Twisted Tide once again involves Lacey Flint in spite of herself. After her leave of absence, instead of working as a detective she has gone back to uniform as part of the river police, hoping to return gradually to the force, but quiet time is not in the cards. Only Lacey could be out swimming at high tide in the Thames River (a hobby she has taken up since moving onto a houseboat) and discover a body floating in the river wrapped carefully in white burial cloths. Soon it becomes obvious that she didn’t find it by accident, that once again someone is focused on her, trying to draw her in. Being Lacey, she lets herself be drawn. This one, I have to say, was a little weird in spots even for me—but I enjoyed it. I had two problems: First, I think it’s time for Bolton to take up a new story line with regard to Lacey—not every case can relate specifically to her! Second, the long-drawn-out non-courtship of Lacey and Detective Mark Joesbury can’t be prolonged beyond a point, and I think we just hit that barrier as readers. To quote my British friends, at least give us a little snogging!

The two novellas that Bolton wrote for this series exclusively as

e-books are equally compelling and mysterious. In the first, If Snow Hadn’t Fallen, something happens in Lacey’s neighborhood that weighs on her mind, because none of the explanations for it add up to what the killers attempted to convey. The second, Here Be Dragons, which falls at the end of the series, is a long-needed exposition of Mark Joesbury, detailing one of his undercover cases and leaving us, finally, with a cliffhanger regarding his relationship with Lacy. There have been two stand-alone books written and published since the #4.5 novella with the tease at the end; when, oh when, will we discover the outcome?

One of the things I like about this series is that Bolton has nicely combined two separate mystery subgenres. Her protagonist is a lone-wolf type, and we get all the fun that goes along with that; but the books are also pretty comprehensive police procedurals, detailing all the myriad ways in which the police go about solving a murder. This gives the lone-wolf concept a nice, solid background on which to rest.

These books are beautifully written, with a wealth of detailed description of the characters, the neighborhoods of London, and the beauties of the natural world that make themselves known even

along the dreariest parts of the river Thames. Both the characters

and the mysteries are sufficiently unique and well developed that

I would venture to say if you are a Tana French fan you would love these books.

They also remind me of Carol O’Connell’s series featuring Kathleen Mallory: Lacey Flint is likewise a damaged, somewhat amoral police detective who does everything according to her own instincts regardless of policy and logic, and gets “up people’s noses” even though she has no desire or intention to do so. I think Bolton has been wise, however, to vary her oeuvre with completely unrelated stand-alones; O’Connell’s Mallory has a distressing sameness from book to book as her series unfolds, and Bolton could fall into that trap with Lacey if she focused solely on her as a protagonist. That’s not to say I don’t want more of Lacy, because I do! But I will wait at the pleasure of Ms. Bolton and meanwhile enjoy everything else she has written, which is considerable.

Glacial thrills

No matter where she takes you or what unlikely scenario into which she drops you, Sharon Bolton never disappoints. I first discovered her when I picked up one of her stand-alone novels from the new books shelf at the library a few years ago, and I haven’t missed one since. I equally enjoyed her four-book (and two-novella) series starring Detective Inspector Lacey Flint.

I recently received a notice from Goodreads that Bolton had published a new novel, but when I went to check out the e-book from the library, it was a three-week wait. Undeterred, I put it on hold and decided, while I waited, to reread the Lacey Flint foursome plus novellas. I managed to read books one and two and the first novella, but received book four while waiting for book three and didn’t want to go out of order, so I read something else. Then The Split, her new one, became available, so I enthusiastically jumped over to that.

The story begins with Dr. Felicity Lloyd, a glaciologist (yes, there is such a thing) who has been living in Antarctica on the remote island of South Georgia for the past nine months. She is part of a research team there to study flow and the draining of lake waters as the precursor to the breakup or “calving” of glaciers. Although this research is the dream job of her career, Felicity has an additional reason for retreating to this forbidding landscape: Her ex-husband, Freddie, who abused her terribly while they were together, has written to tell her that he is out of prison and wants to see her. Although Felicity feels fairly secure at her post at the end of the world, cruise ships do arrive from time to time, and she watches their manifests scrupulously. When the Storm Queen faxes over a list of passengers with Freddie Lloyd’s name on page five, Felicity knows she has to take drastic action to escape him. She packs up and heads for a deserted mining town on the other side of the island. Freddie follows, but is foiled in his attempt to get to Felicity by a woman named Bamber, who confronts him, gun in hand…

The story begins with Dr. Felicity Lloyd, a glaciologist (yes, there is such a thing) who has been living in Antarctica on the remote island of South Georgia for the past nine months. She is part of a research team there to study flow and the draining of lake waters as the precursor to the breakup or “calving” of glaciers. Although this research is the dream job of her career, Felicity has an additional reason for retreating to this forbidding landscape: Her ex-husband, Freddie, who abused her terribly while they were together, has written to tell her that he is out of prison and wants to see her. Although Felicity feels fairly secure at her post at the end of the world, cruise ships do arrive from time to time, and she watches their manifests scrupulously. When the Storm Queen faxes over a list of passengers with Freddie Lloyd’s name on page five, Felicity knows she has to take drastic action to escape him. She packs up and heads for a deserted mining town on the other side of the island. Freddie follows, but is foiled in his attempt to get to Felicity by a woman named Bamber, who confronts him, gun in hand…

At this point, we are transported back 10 months to Cambridge, England, where Felicity lives and works at the University, and where she has just received the offer to go to South Georgia. Only one impediment stands in the way of accepting the job: She has recently been attacked, but has no memory of who hurt her or why, and the University has mandated that she see a therapist. Unless she can convince the therapist to sign off on her good health, she will lose this amazing opportunity, which is also the perfect hiding place from her past. Dr. Joe Grant, her therapist, realizes she is trying to manipulate his diagnosis, and the better he gets to know her, the more troubling her problems become. Dr. Grant is, himself, recovering from the loss of a woman with whom he was working as part of his pro bono community service, while his mother, Delilah, a police officer, is pursuing the killer of two homeless women.

During the next six weeks red herrings abound, and ultimately you don’t know who to suspect of what, and why. Bolton does her usual good job of keeping her reader breathless with anticipation at each turn in the road, and provides the unexpected at every one. Fast-paced, well written, and exciting, this is a twisty thriller made even better by its vivid descriptions of its unusual landscapes and the careful delineation of each character. Sharon Bolton, as I discovered when I read her last published book—Dead Woman Walking—can get you to believe practically anything, no matter how unlikely, and The Split reinforces that assessment.

Journalism & crime

On May 26th, a surprise arrived via my Kindle. I had completely forgotten that I had pre-purchased Michael Connelly’s new novel, Fair Warning, to be delivered as soon as it was published, and suddenly there it was! I had another book mid-read, so I have just finished it.

On May 26th, a surprise arrived via my Kindle. I had completely forgotten that I had pre-purchased Michael Connelly’s new novel, Fair Warning, to be delivered as soon as it was published, and suddenly there it was! I had another book mid-read, so I have just finished it.

Connelly leaves the world of Harry Bosch to hark back to gonzo journalist Jack McEvoy, the protagonist of two of his former books, The Poet and The Scarecrow. Although I read both of those books when they came out (I have to date read 34 of Connelly’s books!), it’s been such a long time that I toyed with the idea of revisiting them first before proceeding with the new one, but chose to forge ahead. Although there were a few references to the previous cases in this one, it essentially read like a stand-alone for those who hadn’t read them, so that was fine.

As well as being the title of the book, Fair Warning is the name of a non-profit consumer protection news website run by Myron Levin (which actually exists in real life). Jack is a reporter for this website, which feels like something of a come-down from his former hard-hitting crime beat for the L.A. Times (and his authorship of two best-selling books), but he is quick to point out that consumer reporting is a vital service to the public, especially in this age of accelerating scientific discovery, and that many major papers (the L.A. Times and others) pick up and run with his stories. Maybe he protests too much?

The beginning of this story, however, isn’t professional, it’s personal: Two homicide detectives show up at McEvoy’s door with the news that Tina Portrero, a woman with whom he had a fun, slightly drunken one-night stand (a year previous) has been brutally murdered, and he is a suspect. Jack cooperates to the extent that he provides a DNA sample in order to eliminate himself from their list of “people of interest”; but then, because of a curious mind and an eye for the anomalous detail, McEvoy gets ahead of the detectives on this crime and a bunch of related ones.

The method of the murder (which I won’t mention here) is so dramatic and so extreme that McEvoy researches it, and discovers that this method appears in widespread cases; then he notices that the murderer may have been using personal data shared by the victims themselves in a particular way, to select and hunt his targets.

At this point, McEvoy has ceased to think of himself as an accused murderer and started to see the potential for a really big story that involves solving the murders of a bunch of women, zeroing in on a serial killer, and even calling the government to account for lax practices in data protection. So he decides to reach out to his former lover, Rachel Walling, whose FBI profiling career he burned the last time they collaborated, to see if she can pull some strings for him.

Instead, Rachel jumps into the middle of his quest, perhaps to curry favor with and return to the FBI fold, helping Jack’s information stream but also setting up all kinds of conflicts of interest.

A big part of the story here is the moral quandaries in which the various characters find themselves. McEvoy does want to identify the killer and facilitate his capture; but he also wants to break his story, which means he can’t hand over all his information to the police until he “gets the scoop.” He and Rachel Walling have a chemistry between them that didn’t disappear with their falling-out years ago, so there is a motivation to perhaps rekindle that. In addition, Walling has been pursuing a necessary but boring job since she left the FBI, so the prospect of handing them a serial killer ignites her with the ambition to prove them wrong for firing her. A colleague of Jack’s at the website, who is added to the story by his editor, wants to make a name for herself without treading on Jack’s toes too much to do so; and Jack realizes that although he is the better researcher, she is the better writer, so he reluctantly acquiesces in her involvement but then keeps throwing her under the bus. And of course the police want to be the first, last, and final arbiters of what happens with this case, story scoop be damned. It makes for an interesting level of tension throughout the story.

Connelly has pulled off a gripping, fast-paced tale whose interest level is enhanced by having a reporter, rather than a detective, at the helm. Some of the true-to-life details of data collection and (the lack of) government regulation are chilling, and he also fills in the reader on some aspects of operating on the dark web, as well as providing the usual details of his Los Angeles setting that are fun for those of us who live here and recognize them. I enjoyed this book, and it was a nice change from the Bosch litany.

And no, I have no idea why there is a black bird (a crow? a raven?) on the cover.

Ninth House

I have been anticipating reading Ninth House, by Leigh Bardugo, for several reasons: Although I didn’t care for her Grisha series because it was so full of angsty teenage indecision, I absolutely loved the duology Six of Crows and Crooked Kingdom, particularly the latter. I felt like Bardugo had stepped up her style and discernment by a lot in the second series, and also, I can’t resist a “gang of thieves” story.

I’m really not sure why Ninth House has been identified as an adult, rather than a teen, book. Admittedly, it’s far too gory and explicit for younger teens, but I could definitely see some of my former book club members from the 10th-12th grade club enjoying this. After all, the philosophy in writing for children or teens is that they always want to read “up,” which is to say, they want to read about a protagonist who is a year or two older than they are. As a freshman at Yale, the Ninth House protagonist, Alex Stern, is just the right age to appeal to seniors in high school. I imagine many parents of said older teens would still quibble with me, because they feel their children should be protected from such graphic fare; and there is a part of me that thinks everyone should be protected from it! But as you learn from reading a lot of books, sometimes you need that stuff to make a point, to expose a wrong-doing, to create empathy in your reader. (Plus, of course, for dramatic effect in your adventure story.) There were certainly plenty of opportunities for that here!

I’m really not sure why Ninth House has been identified as an adult, rather than a teen, book. Admittedly, it’s far too gory and explicit for younger teens, but I could definitely see some of my former book club members from the 10th-12th grade club enjoying this. After all, the philosophy in writing for children or teens is that they always want to read “up,” which is to say, they want to read about a protagonist who is a year or two older than they are. As a freshman at Yale, the Ninth House protagonist, Alex Stern, is just the right age to appeal to seniors in high school. I imagine many parents of said older teens would still quibble with me, because they feel their children should be protected from such graphic fare; and there is a part of me that thinks everyone should be protected from it! But as you learn from reading a lot of books, sometimes you need that stuff to make a point, to expose a wrong-doing, to create empathy in your reader. (Plus, of course, for dramatic effect in your adventure story.) There were certainly plenty of opportunities for that here!

Within the first few pages of this book, I seriously considered putting it down without finishing it. There is a scene early on in which a group of students from one of the magical “houses” at Yale performs a “prognostication” by reading the innards of a man who is still alive (although sedated), with his stomach cut open and pinned back; when they’re done, they stitch him up and send him off to hospital without another thought for his well-being. Also present at the ritual were a group of “Grays,” ghosts who gave off a really frightening vibe. The entire scene turned my stomach, and since I hadn’t as yet invested much into either the story, the scene, or the protagonist (and didn’t really want to encounter more of this), I thought about stopping. But surely all my friends—both personal and Goodreads-type—who were bowled over by this book couldn’t be wrong? So I kept reading.

Ultimately, I was glad I did. Although it took a long time to understand what was happening and also to bond with the main character, I eventually came to appreciate both the bizarre behind-the scenes action and the dogged, flawed, yet honorable Alex, who didn’t give up no matter what.

“Could she grasp the ugly truth of it all?

That magic wasn’t something

gilded and benign, just another

commodity that only

some people could afford?”

Some things I liked about the book:

It gives this Ivy League school an ulterior motive for existing that is both completely creepy and also believable. The concept of a university elite is nothing new, but the idea that they became that way by the practice of necromancy, portal magic, splanchomancy (the reading of entrails), therianthropy (basically, shape-shifting), glamours, and the like is certainly novel!

The funniest part of this is at the end of the book, in an appendix, where the author describes the eight occult houses, reveals in what talent or magic each is invested, and then names graduates (from the real world) who have benefited by being members of the houses during their careers at Yale.

This is not just an amusing commentary, however, on how these students one-upped their futures by participating in magical solutions on the sly. As highlighted in the quote above, Alex comes to realize that magic, while theoretically accessible to whoever was trained or born to practice it, was in reality a tool of the rich and privileged that was sought after at the expense of the poor and defenseless. This is a huge theme of the book, and this is why the reader is able to bear with all the dark scenes, because they are so illustrative of our own contemporary world where billionaires are tripling their wealth during the pandemic while so-called “essential” workers are flogged back to their minimum-wage jobs, despite the danger, by the threat of unemployment. I don’t know if she intended it, but Bardugo here reveals the true “deep state” of influence, bought and traded favors, and a deep disregard for anyone who gets in the way.

Up against this mostly impenetrable and nearly unbeatable system of advancement is Galaxy “Alex” Stern, an underdog heroine if there ever was one. She is recruited (and given a full ride to Yale) to be a member of a secret society, Lethe, whose officers are trained to monitor the other eight houses for stepping over the line, and to report and penalize them when they do. Alex wants to use her special abilities for good, but quickly realizes that her job is mostly for show, and that there will be few consequences for any of these offenders, because to bring their activities out into the light would mean embarrassment for alumni, for administrators, and for Yale itself as an institution. What the people who recruited her don’t realize, however, is that first, Alex has abilities about which they (and at first she) are unaware, and that second, Alex has been conditioned by life as an almost constant victim to fight for herself and for other victims no matter how hard the going.

At its heart, Ninth House is a giant (and cleverly structured) mystery. There is a contemporary murder, there are disappearances of vital personnel, there is a string of dead girls from the past that may tie in, and Alex, despite discouragement from both her mentors and her opponents, is determined to solve it in order to bring justice for the have-nots that she sees as her equals.

But the book is not single-minded. There are also themes of friendship and (nonromantic) love, and a lot of social commentary. There is the gradual evolution, also, of the book’s characters as they confront issues and reflect upon their responses. One early-on thought from Alex that I loved was when she was pondering how easily things change from “normal” to not:

“You started sleeping until noon, skipped one class, one day of school, lost one job, then another, forgot the way that normal people did things. You lost the language of ordinary life.”

There were also, in amongst some fairly gruesome scenes that (if you are squeamish, you should be aware) include drug abuse, coercion, murder, rape, and the like, some inside jokes about college that I enjoyed, including some funny dormitory moments among roommates. One library-oriented joke, as noted by my Goodreads friend Lucky Little Cat, was, “I especially liked the special-collections library where occult search requests result in the delivery of either an avalanche of barely relevant books or one lonely pamphlet.’ Anybody who has been to college has encountered this result, with absolutely no occult assistance whatsoever!

Be aware that some readers have accused Bardugo of racism (because of a few comments on Alex’s Mexican origins), and of blatant sexism and misogyny in her portrayal of the rape scenes in the book (because they are pictured from the observer’s point of view rather than that of the victim’s). You will have to decide for yourself how you feel about these accusations.

Bottom line, apart from a rather confusing and disjointed few pages at the beginning, I found this to be a clever, nuanced read about white privilege (as symbolized by magic!) and the lengths to which people will go to cling to it. It also has both a protagonist and a secondary character that, while the book has a satisfactory ending, you are longing to follow into the sequel, which will hopefully be produced quickly.