2020 Faves

I don’t know if anyone is dying for a reprise of my favorite books of 2020. Since I am such an eclectic reader, I don’t always read the new stuff, or the popular stuff. Sometimes I discover something popular three years after everyone else already read it, as I did The Hate U Give this past January (it was released in 2017). Sometimes I find things that no one else has read that are unbelievably good, and I feel vindicated by my weird reading patterns when I am able to share it on my blog. But mostly I just read whatever takes my fancy, whenever it comes up and from whatever source, and readers of the blog have to put up with it.

Anyway, I thought I would do a short summary here of my favorite reads for the year, and since they are somewhat evenly populated between Young Adult and Adult books, I will divvy them up

that way.

YOUNG ADULT DISCOVERIES

Fantasy dominated here, as it commonly does, both because fantasy is big in YA and because I am a big fantasy fan. I discovered a stand-alone and two duologies this year, which was a nice break from the usual trilogy and I think worked better for the authors as well (so often the middle book is weak and the last book is rushed in those cases).

The first was The Hazel Wood and The Night Country, by Melissa Albert, and although I characterized them as fantasy, they are truthfully much closer to fairy tale. I say that advisedly with the caveat that this is not the determinedly nice Disney fairy tale, but a real, slightly horrifying portal story to a place that you may not, in the end, wish to visit! Both the story and the language are fantastic, in all senses of the word.

The stand-alone was Spinning Silver, by Naomi Novik. The book borrows a couple of basic concepts from “Rumpelstiltskin,” turns them completely on their heads, and goes on with a story nothing like that mean little tale. There are actual faerie in this book, but they have more to do with the fey creatures of Celtic lore than with any prosaic fairy godmother. It is a beautifully complex, character-driven story about agency, empathy, self-determination, and family that held my attention from beginning to end.

The second duology was The Merciful Crow and The Faithless Hawk, by Margaret Owen, and these were true fantasy, with complex world-building (formal castes in society, each of which has its own magical properties), and a protagonist from the bottom-most caste. It’s a compelling adventure featuring good against evil, hunters and hunted, choices, chance, and character. Don’t let the fact that it’s billed as YA stop you from reading it—anyone who likes a good saga should do so!

I also discovered a bunch of YA mainstream/realistic fiction written by an author I previously knew only for her fantasy. Brigid Kemmerer has published three books based on the fairy tale “Beauty and the Beast” (and they are well done), but the books of hers I fell for this year were about typical teenagers with problems that needed to be solved and love lives that needed to be resolved. My favorite of the four was Letters to the Lost, but I also greatly enjoyed More Than We Can Tell, Thicker Than Water, and Call it What You Want.

These were my five-star Young Adult books for 2020.

ADULT FICTION

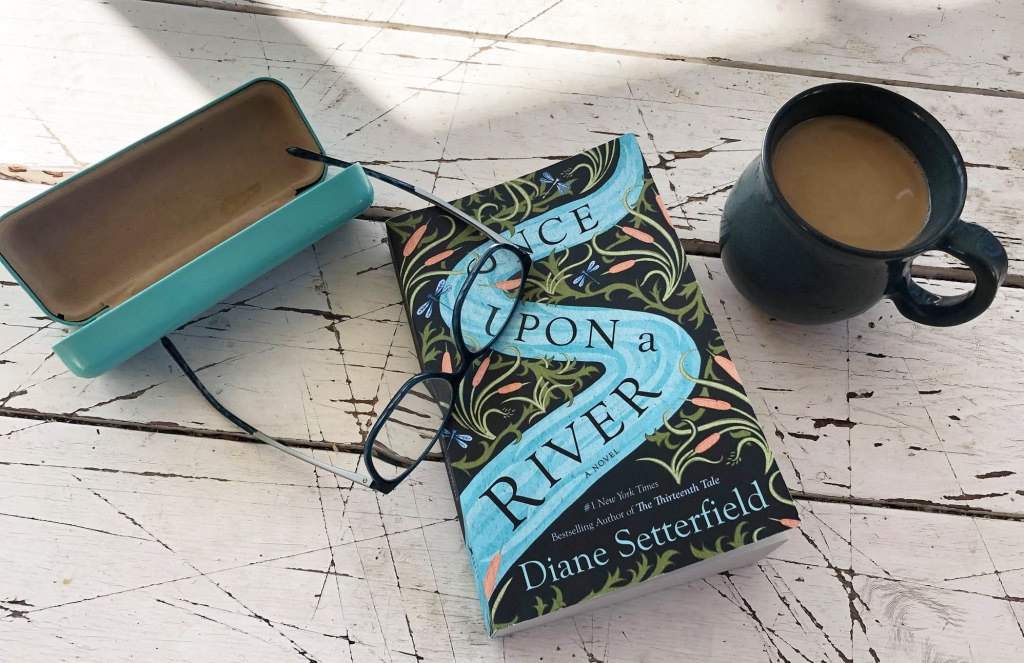

As YA selections were dominated by a particular genre, so were my books in Adult fiction, almost all of them falling in the mystery section. But before I give you that list, I will finish up with fairy tale by lauding an original adult story that engaged me from the first page and has stuck with me all year: Once Upon A River, by Diane Setterfield. The fairy tale quality is palpable but the archetypal nature of fairy tales doesn’t dominate the story, which is individual and unique. It is the story of three children and the impact of their disappearances (and possible reappearance) on the people close to them, as well as on the inhabitants of one small town beside the river Thames who are caught up by chance in the events that restore a child to life. But the story encompasses more than her fate: It gives extraordinary insight into the issues of life and death—how much they are worth, how they arrive, how they depart, and what is the best way to pursue them.

Another book I encountered in 2020 that didn’t fall into the mystery genre or belong to a series was the fascinating She Rides Shotgun, by Jordan Harper. This was a short, powerful book by a first-time author, a coming of age story set down in the middle of a dark thriller that bowled me over with its contradictory combination of evil deeds and poignant moments.

And the last stand-alone mainstream fiction novel I enjoyed enough to bestow five stars was Just Life, by Neil Abramson. The story showcases the eternal battle between fear and compassion, and involves a deadly virus and a dog shelter in a fast-paced, gripping narrative that takes over the lives of four people. It made me cry, three times.

Most of the mysteries I enjoyed this year came from a “stable” of staple authors I have developed over the decades and upon whom I rely for at least one good read per year. The first is Louise Penny, whose offering All the Devils Are Here in the ongoing Armand Gamache series is nuanced, perplexing, and utterly enjoyable, all the more so for being extracted from the usual Three Pines venue and transported to the magical city of Paris.

Sharon J. Bolton is a reliable source of both mystery and suspense, and she didn’t disappoint with The Split, a quirky story that takes place over the course of six weeks, in stuffy Cambridge, England, and remote Antarctica. Its main character, a glaciologist (she studies glaciers, and yes, it’s a thing) is in peril, and will go to the ends of the earth to escape it…but so, too, will her stalker, it seems. The Split is a twisty thriller abounding in misdirection, and definitely lives up to Bolton’s previous offerings.

Troubled Blood, by “Robert Galbraith,” aka J. K. Rowling, is my most recent favorite read, and is #5 in that author’s series about London private detective Cormoran Strike and his business partner, Robin Ellacott. It’s a police procedural with a lot of detail in service of both the mystery and the protagonists’ private lives, it’s 944 pages long, and I enjoyed every page.

Finally, this year i discovered two series that are new to me, completely different from one another but equally enjoyable.

The first is the Detective Constable Cat Kinsella series by Caz Frear, which currently encompasses three books. I read the first two earlier in the year and promptly put in a reserve at the library on the third (which had yet to be published at the time), and Shed No Tears just hit my Kindle a couple of days ago. They remind me a bit of Tana French, although not with the plethora of detail, and a bit of the abovementioned Sharon Bolton’s mystery series starring Lacey Flint. Cat is a nicely conflicted police officer who comes from a dodgy background and has to work hard to keep her personal and professional lives from impinging one upon the other, particularly when details of a case threaten to overlap the two. I anticipate continuing with this series of novels as quickly as Frear can turn them out.

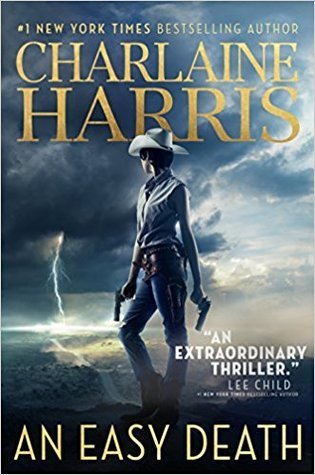

The second, which is a mash-up of several genres, is Charlaine Harris’s new offering starring the body-guard/assassin Gunnie Rose. I read the first two books—An Easy Death and A Longer Fall—this year, and am eagerly anticipating #3, coming sometime in 2021 but not soon enough. The best description I can make of this series is a dystopian alternate history mystery with magic. If this leads you to want to know more, read my review, here.

These are the adult books I awarded five stars during 2020.

I hope you have enjoyed this survey of my year’s worth of best books. I am always happy to hear from any of you, and would love to know what you found most compelling this year. I think we all did a little extra reading as a result of more isolation than usual, and what better than to share our bounty with others?

Please comment, here or on Facebook, at https://www.facebook.com/thebookadept. Thanks for following my blog this year.

And a timely sequel

I previously enthused here about The Merciful Crow, by Margaret Owen, and mentioned how excited I was to move on to the sequel, The Faithless Hawk. I picked that book up this week, and right away discovered two things I liked about it:

- It continued to be timely, in the same weird way as was the first book, as far as its association with current events is concerned;

- Although I had thought (I think because of the title of #2, which didn’t seem to indicate finality) that this was going to be a trilogy, it turned out to be a duology, complete in two books. I wouldn’t have minded reading more about these characters, but the second book was as tightly and dramatically written as the first, and you couldn’t ask for a better wrap-up. Since so many times a trilogy turns out to have either a weak second book or a rushed-to-be-completed third one, I was satisfied and happy with the arc of this two-book story.

The second book picks up about a month after the first one left off; Fie’s troop of Crows are still on the road, and they’re taking her Pa to a Crow way station, which is the equivalent of retirement. He will live there and provide safety and supplies for all Crow troops who seek sanctuary. While at his designated way station, Fie meets with an enigmatic caretaker who is supposed to be the contemporary stand-in for the mythical god “Little Witness.” But to Fie’s surprise, awe, and unease, the person she meets is the actual Little Witness, and she hints things to Fie about her past and her future that are truly disquieting. One of them is that Fie has not yet fulfilled her contract with the Covenant, which she thought she had met by saving Prince Jasimir and bringing him to the General who is keeping him safe while championing his cause. But apparently Fie’s indebtedness to the Covenant goes back many lifetimes and is, in fact, the reason why the Crows roam friendless on the roads.

Just when Fie is absorbing all of this, she and her troop learn of the death of the king, Surimir, by Plague, and they decide to make their way to the Prince, who is with General Draga and her son Tavin, Fie’s love (and the Hawk of the title). A short time after they reunite, however, they are all thrown into dismay and confusion by the machinations of Queen Rhusana, who will do anything to ascend the throne. Once again Fie realizes that the fate of the kingdom may rest on her unready but stubborn shoulders.

In The Merciful Crow, the focus was much more on the journey (both physical and metaphorical) made by Prince Jasimir, Fie, and Tavin, discovering more about the current situation of the kingdom and about each other, and specifically cultivating the romance between Tavin and Fie. By comparison, The Faithless Hawk focuses on a bigger picture: the system of magic, the history of the various castes’ birthrights, and politics in general. This book really fleshed out the world-building, but it didn’t neglect its characters; we also get to learn more about Fie and start to fathom why she is such a central character to this conflict.

The content I mentioned at the top of this review—about its being timely and in synch with current events—has to do with the examination of the entire system of governance, caste, and society. One character remarks,

“We made a society where the monarchs could ignore the suffering of their people because it was nothing but an inconvenience, and we punished those who used their position to speak out.”

I don’t want to give away the entire plot here, but a seminal part of this story is how the characters come to realize that if this world is going to work for everyone, simply substituting a new ruler at the pinnacle of the government probably won’t serve. The rules and systems need to be examined, and must adapt, change, or be abolished in order to make things safe for all people going forward. In The Faithless Hawk, it takes the predations of an unexpectedly corrupt ruler and the threat of a worldwide plague to make that plain.

Some trigger warnings about this duology: There are seriously gory, disgusting scenes with realistic and thorough descriptions of what has occurred; and the use of teeth in their form of magic/wizardry is creepy/troubling (especially to those of us with dental anxiety to begin with). But the books are well worth a few squeamish moments for their powerful portrayals. I hope this immersive fantasy gets the attention

it deserves.

The Disenchantments

Best friends Colby and Bev made up their minds in middle school that they were not going to be ordinary, were not going to do what everyone else does after high school—go to college, especially as a default. They may go to college someday, maybe even in a year, but in between, they want to have an adventure. They have been saving their money since they were 14, and are all set to spend some time with Colby’s mother in Paris (she’s there taking an immersion French class), and then go to Amsterdam, see a whole archipelago of islands and…who knows what else? The year is before them, and it’s up to them to choose. All their classmates are in awe of their plan, including sisters Meg and Alexa, the other two members with Bev in an enthusiastic (if not terribly good) girl band called The Disenchantments. The plan is: Graduate, spend a week on the road doing gigs with the band in small towns between San Francisco and Portland, drop Meg at her college there, take Alexa (who is a year younger and won’t graduate until next year) back home to San Francisco, and fly.

Imagine, therefore, how Colby feels when he pulls up in his uncle’s VW van to pick up the girls for their road trip, mentions to Bev (for the third time) that they really need to buy their plane tickets, and Bev blurts out that she has been accepted to the Rhode Island School of Design and isn’t going with him to Europe. She tries to play it off like a last-minute exciting chance that she got accepted…but we all know (as does Colby) that to get into a college you have to apply, to send transcripts and letters of recommendation and (for a prestigious art school) put together a portfolio. So this wasn’t exactly spontaneous, and yet Bev has gone along with him for months, supposedly sharing his enthusiasm for reading travel guides, making note of cool restaurants and must-see museums, and lying the whole time. And now they are shut up in a van together for a week, and Bev won’t talk or tell him why. It doesn’t help, of course, that Colby cherishes unrequited love for Bev.

This all sounds like a set-up for a slog through romantic teen angst, but it doesn’t turn out that way, not for the most part. For one thing, the chemistry between the four of them, the adventures they have while playing their gigs, and the good intentions of all involved—despite bad behavior—save the story from the utter mawkishness that it could have become. While relationships are important to the story, they encompass more than the romantic—we see the connections with family, friends, strangers that turned into friends, and strangers encountered once and left behind, and the book features some real moments with all of those.

The book was more of a quest for understanding and purpose, with Colby pondering his options for the next year. At that age, making a choice seems so definite and so daunting, but with Bev’s defection he is forced to realize that it’s really all up to him. Nina LaCour has set up a story that deals kindly and imaginatively with beginnings and endings, and captures both the intensity and uncertainty of teens on the cusp of adulthood.

It’s also a fun catalog of music preferences amongst the four, and the story of what it’s like to play your music in questionable venues you booked sight unseen, as well as a separate small quest to find out the origins of a tattoo—all of which lightens the mood from what could have been a fatally serious story.

I wish that whoever designed the cover had paid a little more attention. Some of the details of the four teens are right, and some are dead wrong, and it would have been so simple to dress them appropriately for this cover shoot so you could have teenagers say “Wow, that looks just like them!” The descriptions were vivid—why not go with them?

In terms of age group, I would say 15 and up.

Enchanting

Did I mention that I can’t resist a book with ravens, crows, or other corvids? Or a book that features an artist or painter? I found one that incorporates both, and bought it mostly based on its title and cover: An Enchantment of Ravens, by Margaret Rogerson.

The story in brief: Isobel is a portrait painter who lives in Whimsy, a town outside of time (it’s always summer there, the seasons never change) because it is adjacent to Faerie and the “fair folk” like to wander the town in their avid pursuit of what they call “Craft,” which is anything creative made by human hands. Faerie don’t “do” Craft—in fact, if they take up a pen, a brush, a sewing needle, they crumble to dust. So they are eternally fascinated by its expression, and will pay in valuable enchantments.

Although she has made many portraits of and for the fair folk, Isobel’s most esteemed patron is Gadfly, who seems particularly smitten with himself and for whom she has painted multiple pictures. One day Gadfly tells her he has recommended her to Rook, the autumn king, who wishes a portrait. This flusters Isobel, because of his rank and because he hasn’t been seen in a hundred years. But he turns out not to be so intimidating (although definitely self-regarding), and while painting him, Isobel and he develop an affinity for one another, although it is far stronger on Rook’s part than it is on Isobel’s. She knows better than to fall in love with a member of the fair folk—that would be to break the “Good Law,” and there are two choices after the law is broken: Death to both faerie and human, or the human drinks from the Green Well and becomes a faerie herself. Since she desires neither, she protects her heart and remains wary.

As she paints Rook’s portrait, however, she struggles for the first time with a likeness, and when she finally solves the problem, she has inadvertently painted human sorrow in the eyes of the autumn king. He is so incensed by this that he drags her off to his court to stand trial for this crime, and that’s the beginning of their adventure together.

I enjoyed reading the first part of this story quite a bit: The details of the painting were realistically rendered, and the banter between Isobel and her clients was entertaining, as were her behind-the-scenes thoughts and her back story. I gave a big sigh as I continued, however, because I thought to myself, This is going to turn into a typical mushy YA romance—they will probably fall in love and it will end disappointingly.

I was pleased and relieved to discover myself mistaken: Isobel has a lot more to her than do most YA heroines, and she sees her adventure with Rook as a task to endure and complete with the goal of getting back to her foster mother, Emma, and her twin “sisters,” March and May (they were formerly goat kids, turned into girls by a drunken fair one and adopted by Emma and Isabel). It is her stubborn resolution that saves her (and sometimes Rook) from misadventure for a good part of the book.

I won’t reveal more of the story; I will only say that while parts were predictable fairy tale trope, most of it is fresh and not typical. See for yourself—it’s not a long read, and I found it entertaining.

If you like it, you might also enjoy The Bride’s Farewell, by Meg Rosoff; Far, Far Away, by Tom McNeal; or Reckless, by Cornelia Funke, all of which are different from one another but share the quality of quirky original fairy tale with An Enchantment of Ravens.

Dystopia 4 kids

As a teen librarian, I have been recommending Charlie Higson’s “Young James Bond” books for years to kids of a certain age, but in all that time I never really registered his other series, although we stocked it. Recently, I saw the first book offered at a discount and picked up a copy of The Enemy, his first in a series of six dystopian/zombie books.

“Zombie” is a little bit of a misnomer for the villains in these books: Some kind of plague washed over the City of London (or the world? nobody in this first story knows for sure), and everyone over the age of 14 caught it. They first got sick, and then they lost their minds; some of them died, but the rest went around indiscriminately trying to eat anything that wasn’t nailed down, including their own families. So all the kids 14 and below are on their own, figuring out how to survive and having to fight off the grownups or, as some poignantly call them as they shamble around the city, the “moms and dads.”

The story opens on a crew of about 50 kids who are living in an abandoned Waitrose supermarket building, which two of their number who are good with mechanics have secured with the previously existing metal shutters and some other nifty reinforcements. They’ve been doing okay up to now, but since the food in the supermarket ran out, they have had to forage farther afield to feed everyone, and have had to accept things to eat that they wouldn’t previously have considered. So when they check out the underground swimming pool at the local rec center and see an untouched vending machine full of Mars bars and Cokes, they could be forgiven for not being as careful as they should have been with their scouting efforts before jumping into the pool to retrieve the booty. This is the first graphic incident in which we see the ruthlessness of the enemy they are up against, and this is when Higson lets the reader know not to get too fond of anyone, because everyone is disposable!

The writing is so atmospheric, almost like a script in the way it sets up and delivers scenes to the reader. It’s also (be warned) bloody, graphic, and gruesome, almost to the level of The Monstrumologist, by Rick Yancey, which is saying something! But to alleviate that atmosphere, there are strong friendships and alliances, distinctive characters, witty banter, and a powerful narrative voice.

This series couldn’t help but bring to mind the equally gory Gone books by Michael Grant, in which a strange translucent dome comes down over a beach town and all the adults are magically transported elsewhere, leaving the kids to fend for themselves. I believe both authors drew on the classic Lord of the Flies, by William Golding, and Higson also cites I Am Legend, by Richard Matheson, as his inspiration. I enjoyed Grant’s first book but honestly felt that by book three he had jumped the shark; I hold out much higher hopes for Higson’s tale of horror.

Higson says in an interview (at the back of the book) that his two “wants” were to write a book where the kids were in charge and supposedly free to do whatever they wanted (on your own in London! Wheee!), but also a book that was truly scary because they were impeded by a serious problem. One of his readers confided in Higson that he felt safe reading the James Bond books because the protagonist does grow up to be, well, James Bond, so he’s never going to get seriously hurt or killed off. Higson accepted that as a challenge for this series, and says that he would purposefully write his characters to be endearing in some way to the reader before deciding to eliminate them, and also that he would read his pages to his son before bed to see if they were scary enough to give him nightmares. (Note to Social Services: Don’t give Higson custody of any more kids.)

The book is scary, and also gripping as the kids are approached by an envoy from another group, whose members have taken over and are living in Buckingham Palace and want the Waitrose kids and another group from the same Holloway neighborhood to join up with them. They claim the neighborhood is much more secure there, as are the grounds and buildings of the Palace, and that they are growing their own food to provide for themselves, so they need the help. The Waitrose kids wonder: Is it salvation, or is it a trap?

Because everything in life is always a little too good to be true, there are of course things they are not being told by their prospective hosts. They also run into some serious hiccups in getting across town to the Palace, and begin to notice disturbing new behavior from some of the grownups, who seem to be becoming both more aware and more organized. Then there are the hidden dangers from zoo animals in the park, evil people living in the tube stations…you name it, there are perils on every side.

The brilliance and also the frustration of this series is that the first book begins well after the main action has already transpired, and because you only have the children’s perspectives, you don’t know what happened: Was it really a plague, some kind of biological weapon gone wrong, or something else? No one knows or even wonders much any more—it happened, life changed forever, and at this point, it just is. The big question on everyone’s mind who is old enough to speculate: What happens when their oldest members

turn 14?

On Goodreads I discovered that book #2 jumps back in time and is a sort of prequel to fill you in on some of what has gone before. I can’t wait to find out.

My experience with series is that I am always on a seesaw trying to decide whether I hope to love it or hope to hate it; for one that has seven books in it, I dip a little more towards “hope to hate” because taking a time-out from my headlong rush to read everything in one big eclectic mashup in order to pursue one series by one author makes me feel a bit stalled in my tracks. On the other hand, if it’s a good series, there’s the payoff. I don’t think I will read #2 immediately (I have 12 books in the queue ahead of it), but it won’t be that long from now that it persuades me to take it up again. That’s saying a lot, because I am neither a horror nor a zombie aficionado. But I like good writing, good story-telling, and engaging characters, and this series has it all.

The problem novel

In general, I don’t like to go after people’s beloved authors, and Margaret Peterson Haddix is certainly one of those. She has established a constant and abiding presence in Young Adult Literature over decades, mostly through the popularity of her two long series, Shadow Children and The Missing, and the Just Ella books, that all seem to hold their appeal for subsequent generations of young teens.

Last week, I picked up a 2018 stand-alone book of hers (of which she has also written close to 20), and was immediately transported back to the 1980s. That would be fine if the book had been set in the ‘80s, but unfortunately its timeframe was present-day Ohio and Spain. The reason I was feeling the ‘80s vibe was that The Summer of Broken Things is such a typical example of the “problem novels” of the 1980s that took YA Lit from being innovative, gritty, and real to being contrived, preachy and smug.

I teach YA Lit at UCLA in the masters program for librarians, and its history, stretching from the saccharine Seventeenth Summer to the lively and realistic On the Come Up, is a specialty. So I recognize a problem novel when I read one.

Michael Cart, author of Young Adult Literature: From Romance to Realism (2016), says that the success and innovation of the gritty realistic novels of the 1970s bred pale imitation and that “The problem novel is to young adult literature what soap opera is to legitimate drama.” The definition of a problem novel is that the book is more concerned with a condition or social concern, and the characters are manipulated to work out the “lesson” that is the subject of examination.

The initial premise of this book might have been okay. I say “might have” because it was so obviously a set-up for something that it also might have been doomed to failure from the start; but I can see how someone could make this story work better if they tried hard.

The Armisteds are a fairly well-to-do family (David is a business tycoon of some kind, and Celeste is an interior designer) with one daughter, 14-year-old Avery, who has been raised in an atmosphere that satisfies her every whim. David travels a lot for work, and has decided that this summer, instead of Avery going to soccer camp as she would prefer, she will accompany him to Spain for 10 weeks, spending half-days during the week (while he is working) in a Spanish immersion class for teens. He realizes that this is not good news to Avery (even though most teenagers would be stoked to travel in Europe over the summer), so he decides that Avery will bring a friend along. Avery then feels better about the trip—until she realizes that the friend has already been selected for her, and it’s a girl she used to play with as a young child but hasn’t seen in years.

Kayla Butts and Avery were best friends back when Avery was five and Kayla was seven, but although the families have stayed in touch with Christmas and birthday gifts over the years since, there has been no real contact between the girls. Kayla is now 16, and has grown up in circumstances far different from Avery’s: Her father was in an auto accident just after she was born, and has been completely disabled—unable to speak, move, or function—ever since. She and her mother live with her maternal grandparents, and Kayla’s mom works at the nursing home where her husband lives. Kayla has grown up hanging out there, with the result that most of her friends are in their 70s and 80s and, while she is an expert on black-and-white TV reruns such as Gilligan’s Island and The Beverly Hillbillies, she is awkward and baffled when it comes to contemporary culture. It doesn’t help that the family lives essentially paycheck to paycheck and Kayla’s best clothes come from Target (the others are from Walmart or the thrift shop).

Now, suddenly, Kayla has this amazing opportunity to go to Spain for a summer, and she should be glad—but she’s not sure about her role as Avery’s “companion,” she’s uncertain about and made uncomfortable by the accepting of constant “favors” from the wealthy Armisteds, and to put the icing on the cake, Avery is every flavor of spoiled brat and taking out her petulance on Kayla. And while Kayla is well used to being bullied in school for being tall, awkward, and fat, not to mention poor and shy, the prospect of putting up with Avery’s special brand of entitlement all summer is such a disincentive that she’s tempted to jump out of the cab to the airport and go home again.

As I said, this sounds like a set-up that might work: It’s definitely a “learn this lesson” kind of theme, in which Kayla gains confidence and a broader experience while Avery learns to be more generous and think of others as well as herself, but if a story like that is done with subtlety and humor, why not? The unfortunate truth here is that these girls are all kinds of cliché and, not satisfied with setting them up that way, the author continues to punch up every aspect of their personalities that caters to those clichés until they become grotesques.

(Parenthetically, why is it that the poor girl is always the fat, awkward one with mousy hair, and the rich girl is blonde and physically fit? And why do authors feel the need not just to point out these differences but to somehow make it a “redemption” when the poor fat girl steps up her physical activity and “actually” starts to look better? I’m so tired of the fat-shaming, the poor-shaming, the idealization of physical perfection. In this book, it takes the form of Avery bouncing along wherever she goes while Kayla and Avery’s dad arrive sweaty and out of breath. The number of staircases climbed—in the airport, in the Spanish apartment, in the school building—are endlessly and daily enumerated, with the fit girl impatiently urging everyone on and the two out-of-shape people panting and taking rests on the landings. Enough already!)

Further, not satisfied with creating the “problem” of Avery’s entitled snottiness and Kayla’s crippling self-doubt as the theme of the book, Haddix then reaches out for an additional “problem” for both girls that is so obviously manufactured as to be painful. One wonders (because one is constantly coached to do so) from the beginning of the book how these two families became friendly and stayed in touch so relentlessly, considering the material differences in their lifestyles, and this little nugget proves to be the tie that binds, but the way Haddix has the girls react to it is completely over the top. Yes, it’s something they probably both should have known about sooner; yes, Avery has every right to feel somewhat betrayed that her parents didn’t let her in on this secret, and ditto Kayla; but to create such drama around this factoid that doesn’t essentially have any lasting effect on anyone is absurd. Avery spends days in floods of tears. Kayla won’t speak to her mother or read her emails, and contemplates leaving the Armisteds to their just desserts (i.e., each other) and seeking out a youth hostel. The drama ramps up so precipitously and for such an extended period as to become ridiculous, and that’s all before the specter of divorce pokes up its head (that’s a spoiler but you know it’s coming all the way through, so I don’t care).

As if that weren’t enough, a final dramatic moment ensues that insures we get a meet-cute resolution to multiple issues, and by this time all you want, if you are any kind of reader who enjoys realistic character development and a plausible story line, is to throw the book across the room or, say, drop it in the bathtub and leave it there.

There were a few fleeting moments when the story was saved by tertiary characters: The two Bulgarian boys who are taking the Spanish immersion class and who are enthusiastic about Kayla and fairly indifferent to Avery’s charm; the snotty British Susan, who gives both Kayla and Avery good advice and some perspective in the midst of a soccer game involving all their classmates and some Spanish players; and some of the old people at the nursing home whose conversations with Kayla are pretty amusing. But these only make it more obvious that this is a talented writer who could do better but has instead opted for the ultimate in stereotypes to make a story few will fail to see as both flawed and overwrought, right down to the title of the book, which looks at two girls experiencing a European country for the first time and can only focus on what’s wrong with the picture and not what’s right. The only thing I liked unreservedly about this book was its cover, and not because it was relevant but simply because it was pretty.

A timely fantasy

I was a bit conflicted about reading The Merciful Crow, by Margaret Owen—it sounded like just my kind of thing, but a rather stern friend on Goodreads panned it for ableism and said lots of nasty things about it, which made me pause. But it got such consistently good reviews from everyone else that I decided maybe she had a pre-emptive bee in her bonnet when she read it, and went ahead.

First of all, I can’t resist any reference to crows, ravens, magpies…. Second, just the description on Goodreads let me know that it was a book with complex world-building (formal castes in society, each of which has its own magical properties), and that the protagonist and her caste were the scapegoats. I love a scapegoat.

What this book turns out to be (and I can’t decide if Owen purposefully wrote it that way or not, but she had to be aware) is a perfect analogy for Black Lives Matter. The Crows are the bottom-most caste in society, and their duty is wrapped up with their so-called luck: They are the only people on the planet who are immune to the plague. Thus, when a case of plague is reported, a beacon fire is lit and the Crows show up to collect the body and dispose of it before the infection spreads any further. They are also both celebrated (by the dying) and reviled (by everyone else) for being mercy killers: The plague is not a comfortable way to die, and if the sufferers ask for mercy, the Crows will deliver the killing stroke that puts them out of their misery. The only way to stop the plague’s spread is to burn the body and all possessions.

You would think that society would appreciate this service, which protects everyone but the sufferers from a hateful death, but instead the Crows are essentially treated as the equivalent of India’s Untouchables. Not only do they suffer from disparaging remarks and taunts (and sometimes thrown garbage and other insults), but some of the people who seek their assistance then turn around and are reluctant to reward them for their service. The Crows are dependent on the viatik (payment) for survival, since their sole duty is to roam the roads watching for plague beacons, and for that they must have resources—food, clothing, shoes, weapons, wagons. So the Crows have one answer for this, but they mostly suffer anything that comes rather than pull out this ultimate revenge: They refuse to dispose of the body, guaranteeing eventual death by plague to all in that village, which will be quarantined and burnt to the ground.

Fie, the protagonist, is the future chieftain of a band of Crows, and she is learning the various aspects of being a leader from her Pa, including delivering the killing stroke, and what her people call “bone magic”—they save the teeth of dead witches, which can be called upon to deliver various defenses, including inattention (invisibility) and fire. Fie has developed a justifiably cynical attitude in her 16 years as a Crow, watching her Pa and their troop receive more abuse than coin, and so when the royal palace—housing the pinnacle of castes, the Peacocks—sends up a plague beacon, she understandably hopes for a decent payout that will support her people for a while. Instead, the troop receives, along with the bodies of the Crown Prince and his personal guard/body double, the ultimate insult from Queen Rhusana; so when they discover that the two young men have faked their deaths in order to escape the queen’s plans to reign (which have included multiple attempts on the prince’s life), Fie is ready to cut their throats anyway. Instead, she drives a hard bargain with Prince Jasimir: If the Crows help him reach his supporters and he lives to assume the throne, he will materially protect her people—with guards, with respect for their function in his society, with acknowledgement that they are also his people.

The rest of the book is an account of Fie’s desperate attempts to honor her oath. The other members of her troupe are betrayed and taken hostage, and she must step up as chief, making her responsible for getting Jasimir, the Hawk Tavin, and herself halfway across the country of Sabor, undetected by the Oleander Gentry (a group of vigilantes who target Crows), skin witches, ghasts, and everything else the queen can throw at them. It’s an exciting tale of near misses, tragedies, and miraculous recoveries, but what really struck me was the progression of understanding, as the story goes on and the three become more intimate, about what the oath between the Crown Prince and the Crows really means.

Jasimir is the epitome of white privilege: He has been raised in the highest caste, and believes in the abstract that he has a responsibility to rule his people well, but doesn’t take into account that a portion of his people are left out of his concern or indeed of his attention, and that far from being taken care of, they are persecuted at every turn. As he begins to realize the breadth of the bargain he has struck—that he will compel members of his guard, the Hawks, a higher caste than the Crows, to protect them—he and Fie have a series of conversations that reveal how shallow is his understanding of what it means to be an advocate for all of his people, and how unwilling he is to change.

Fie was sick of bartering for her right to exist. She stood to face him down. “And who in the twelve hells do you think Crows are? Someone else’s people? Someone else’s problem? Because you already made my oath with the rest of Sabor: You protect your people and set our laws, and we pay for your crown. That’s your oath as king. You just don’t want to keep it with Crows.”

It’s such an on-point discussion of what those who are at the top are willing to witness in the mistreatment of those at the bottom, without caring or maybe without even noticing, and what happens when this inequity is brought to their attention. Will they step up and do the right thing? Or will they make excuses—it’s too radical a solution, others won’t go for it, maybe someday, of course we’ll take this under consideration, we can’t do that but maybe we can do this…. It’s a microcosm of every so-called conversation between white men in power and black people subject to their influence.

At the same time, it wasn’t obvious or preachy, it wasn’t made clear that this was the secret agenda for which the book was written—The Merciful Crow is a fantastic saga of an adventure, of good against evil, of hunters and hunted, of choices, chance, and character. The protagonist is the perfect mix of uncertain with stubborn, fueled by anger, pride, and honor. Her two companions exhibit their own personalities uniquely and completely. The bad guys are sufficiently overwhelming and scary to justify the terror in which the trio operate at the thought of being caught by them. And the story, as all really good fantasies are, is complete within itself and yet leaves the door open for a sequel (The Faithless Hawk, which is being released today!). I was blown away by this book (especially knowing that this was a debut author), which gave me similar “feels” to Graceling, by Kristin Cashore. It’s billed and published as Young Adult, but recommend it to everyone you know who loves a good saga.

No thieves

I picked up a Young Adult fantasy book mostly because of the title: It’s called Thief’s Cunning, by Sarah Ahiers. Who doesn’t love a good thief story? In fact, one of my favorite books ever is The Thief, by Megan Whalen Turner. Then there’s The Book Thief, The Pearl Thief, The Tale of the Body Thief, The Thief Lord…you get the picture. I have had excellent luck with reading and thieves! My luck seems to have run out, however, with this one.

First of all, despite its title the protagonist isn’t a thief! Allegra is part of a family of assassins (called “clippers”), and in fact the point is made early in the story that if they were to stoop to thievery in the course of their duties as assassins, their reputations would be destroyed. So what the heck? I searched in vain for thieves. There are Travelers in this book, and one of the triad of gods they worship is a sort of patron saint of thieves…but none of the Travelers follow through by stealing anything! There are two “thief” associations that could apply if not for the addition of the second word, “cunning.” The first is that Allegra wears a necklace that properly belongs to someone else, and it is, in fact, forbidden that she wear it. But she was given it by her uncle for her birthday, has no knowledge of its significance until much later, and didn’t in fact steal it. Her uncle could be characterized as stealing it, but there was no cunning involved, it was a simple notion: Mom’s dead, I’m being separated from my people, and I’m taking her necklace to remember her by.

The second association was that Allegra, in the course of her life, has herself been stolen several times and not told from whom, so she doesn’t have a clear sense of who she is. She has grown up with one story, learns there is a completely different one, then gets diverted into a third, and goes to pieces. The kicker line on the cover is, “With her past stolen, she’s taking the future into her own hands.” Um, not noticeably.

And boy, does she whine about it! The entire book is seething teenage rebellion against nothing in particular. Oh, these people took you in and made you a part of their family and loved you, fed and clothed you, trained you, but you can’t stand being with them for one more minute because they’re not “your” family and they lied about it? Oh, you have discovered your real family and long to go to them but you aren’t sure you’ll fit in there either (because they are the sworn enemies of your actual family)? Oh, you have taken up with a lovely boy (who likes you) and his pretty interesting tribe of people, but you still feel caged by their wants and needs and have to be on your own? Well, aren’t you special.

Honestly, apart from the lifestyle details depicted for the Travelers, which were interesting and somewhat in line with Travelers from our culture, I was so wearied by this book. It reminded me of the worst of the teen fantasy novels (I’m looking at you, Throne of Glass), in all of which the heroine can’t decide who she is and, rather than take positive steps to find out, she just lashes out indiscriminately and to no purpose, and gets herself in more and more trouble because she can’t control her temper or her impulsiveness or whatever we’re calling it in that book.

I also didn’t know this was a sequel when I bought it, and was initially going to stop reading it and seek out the first book (Assassin’s Heart), but I quickly realized that the events of the previous novel had taken place 18 years earlier, and plenty of context was given in this one so that I didn’t feel like I missed anything crucial. It’s possible I might have liked this one better had I read that first…but I don’t think so. That one sounds like a fairly kickass story about a woman who goes all out for her goddess and is rewarded with resurrection for her and her companion, which was interesting. Thief’s Cunning was not.

The Kiss-off

Sometimes themes develop accidentally, as you pick up a book here, a book there, and then view all of them at once, deciding what to read next. This particular theme was “fat women,” with one chick-lit debut and one YA by an author already known for heroines with size diversity.

Sometimes themes develop accidentally, as you pick up a book here, a book there, and then view all of them at once, deciding what to read next. This particular theme was “fat women,” with one chick-lit debut and one YA by an author already known for heroines with size diversity.

Reviewing One to Watch, by Kate Stayman-London, forces me to confess a deep and shameful secret: I have been known to tune in to an episode or two of The Bachelor or The Bachelorette. Let me hasten to say that I am not one of what the host calls “Bachelor Nation” (ahem pretentious much?)—in fact, it’s been more hate-watching than anything—but I have, over the many surprising seasons it has continued its hackneyed formulaic road to romance, checked it out. The primary motivation for this is a complex cocktail of wanting to see the pretty people and the exotic locales, to mock the uniformly sincere expressions of all the participants who think they might have feelings for someone with whom they have spent six hours, and to marvel at the idiocy or bewilderment of the families who condone this behavior by one of their own. The primary result has been to irritate my cat, who doesn’t like it when I talk back to the television set, particularly when it’s in a scathing tone; but somehow I am as unable to resist seeing what’s going on just once a season as I am prone to wonder who will win Dancing with the Stars.

For that reason, the idea that the show would cast a bachelorette who was of a body type not seen on television unless the actress is playing a grandmother or a police chief intrigued me. A bachelorette who wasn’t a size 4? One who might actually sit down at one of those candlelit tables and eat the delectable dishes laid out in front of her, rather than spend the whole meal sipping her wine and whining about her feelings? Bring it on.

The whole concept that a normal woman—that is to say, someone closer to the American average of size 16—could be celebrated as desirable to 25 bachelors seeking matrimony is enticing, though problematic. After all, regardless of the inclusion of body positivity, the show is still set up to see romance as a cattle-call competition, with the women as prizes.

I am somewhat embarrassed to say, therefore, that I thoroughly enjoyed this book and would recommend it to someone looking for a story with a protagonist to whom they can relate: Someone who has transformed themselves on the outside but is still vulnerable and afraid beneath the surface; someone who decides she is brave enough to take a chance but who then constantly second-guesses herself based on everything that has been pounded into her by society, her family, other women, the men who have failed to requite her love, and the relentless trolls on the internet.

Bea Schumacher is a confident and stylish 30-year-old plus-size fashion blogger. She has good friends, a loving family, thousands of Instagram followers, but no romance. Her secret crush has strung her along for years, and has recently caused her to swear off men for the foreseeable future. But after she writes a blistering blog post about the show Main Squeeze (The Bachelor, thinly veiled) with its lack of body diversity or, for that matter, any kind of diversity in its legions of skinny white people going on fantasy dates, the show calls her and asks if she will be the next star. Bea agrees, but she tells the show’s new producer, Lauren, that on no account will she actually fall in love. She’s going on the show to make a point about anti-fat beauty standards, and maybe to boost her list of followers into seven figures.

Of course things will get more complicated. Of course she will be upset, confused, intrigued, tempted, repulsed, angered, and beguiled as she spends 10 weeks supposedly looking for love. But she can’t possibly let go of all her preconceived notions and believe in the HEA, can she?

The thing I liked about this book was that it turned the reality show on its ear. Yes, there were meet-cute moments and embarrassing tests and awkward interludes just like on the real-life show, but in between that, because Bea isn’t the usual fare, the bachelors (who are mostly the usual fare, either muscular and dumbly sincere or sharp, handsome, and deeply cynical), get jolted out of their complacency as she attempts to have conversations with them that don’t revolve around the typical inanities. Bea is portrayed as a real person, and she reaches out to find the real person in each of the men she ends up with after the “extras” have been kissed off. (I loved that instead of “will you accept this rose,” the woman here gives them a lipstick kiss or “kisses them off,” depending.) As on the show, you really have trouble trusting that the men are telling the truth about themselves, their feelings, and their motivations, which is compounded in the case of Bea.

I thought the author nailed the struggles of being a plus-sized woman, wavering from confident to terrified as she is confronted by the cruelty of society towards women who don’t conform to insane standards of beauty. (She also had some fun pointing out how a blind eye is turned to men in that same category.) She didn’t fall for the temptation to make her protagonist lose weight in order to find her HEA, she forced the show, the men, and the viewing public to accept Bea as she was.

The depiction of the reality TV world—the way things are manipulated to make ratings, the descriptions of the fancy wardrobe, the tensions of the timetable—were well done, as was the use of the social media inserts into the story—text messages, emails, TMZ articles, tweets, and blog posts all added dimension to the story.

Ultimately, the book does pander to wish fulfillment, but then, what did you expect? It’s a rom-com. But it’s entertainingly written and told, and does have a lot to offer about false standards of beauty and their equation with worth. So I say, a positive review.

By contrast, I became almost immediately impatient with both the author and the protagonist of Julie Murphy’s new book, Faith Taking Flight. I should have known better than to broach this book with no expectations, because I found her previous book, Dumplin’, to be full of contradictions that didn’t lend themselves to her avowed goal of advocating for plus-size teens. But the prospect of a fat girl who could fly grabbed my attention, and I jumped in with enthusiasm.

My enthusiasm quickly turned to dismay and derision as I experienced the thin plot development regarding the flying skills. Faith meets Peter, who tells her she’s been chosen to go through some kind of conversion to turn her into a superhero, because she has the potential to become a psiot. This conversation takes place at the mall. Then he tells her (alarm bells should be ringing) that she has to perpetrate a “cover” for herself over the summer—to tell her grandmother that she’s off to journalism camp. She agrees! She climbs trustingly onto a bus, goes to a secret underground facility, is locked in a room and assigned a uniform and a number, and then realizes she’s an experimental subject. Meanwhile, her granny (her guardian) sends mail and makes phone calls for the entire six weeks that she’s gone; Grandma Lou receives not one response, and doesn’t see this as a problem or institute any kind of inquiry, just assumes her granddaughter is fine? Come on. We discover later (way too late in the book) that Faith actually escapes from the facility with Peter’s help, whereupon she simply goes home and does nothing—doesn’t call the authorities, or wonder about all the other kids who were trapped there with her—she just gets a part-time job at an animal shelter, and resumes school in the fall. But this is the most unbelievable part of the entire story: She doesn’t fly! She has this ability, which would excite most of us beyond belief, and she doesn’t go out every night to try it out? doesn’t practice? doesn’t test her limits or tell her friends? No. She pulls it out when necessary (to save someone from falling off a roof, or to look for her grandmother when she wanders off, a victim of senile dementia) and that’s it. Right.

My enthusiasm quickly turned to dismay and derision as I experienced the thin plot development regarding the flying skills. Faith meets Peter, who tells her she’s been chosen to go through some kind of conversion to turn her into a superhero, because she has the potential to become a psiot. This conversation takes place at the mall. Then he tells her (alarm bells should be ringing) that she has to perpetrate a “cover” for herself over the summer—to tell her grandmother that she’s off to journalism camp. She agrees! She climbs trustingly onto a bus, goes to a secret underground facility, is locked in a room and assigned a uniform and a number, and then realizes she’s an experimental subject. Meanwhile, her granny (her guardian) sends mail and makes phone calls for the entire six weeks that she’s gone; Grandma Lou receives not one response, and doesn’t see this as a problem or institute any kind of inquiry, just assumes her granddaughter is fine? Come on. We discover later (way too late in the book) that Faith actually escapes from the facility with Peter’s help, whereupon she simply goes home and does nothing—doesn’t call the authorities, or wonder about all the other kids who were trapped there with her—she just gets a part-time job at an animal shelter, and resumes school in the fall. But this is the most unbelievable part of the entire story: She doesn’t fly! She has this ability, which would excite most of us beyond belief, and she doesn’t go out every night to try it out? doesn’t practice? doesn’t test her limits or tell her friends? No. She pulls it out when necessary (to save someone from falling off a roof, or to look for her grandmother when she wanders off, a victim of senile dementia) and that’s it. Right.

Meanwhile, we have the secondary plot, which is actually the primary one considering how much space it fills in the 338 pages of the book: The cast and crew of the teen soap opera (The Grove) with which Faith has been obsessed since childhood—to the point where she writes the premiere blog about it and publishes weekly recaps and commentary—moves its filming destination to her town, and the star of the show, Dakota Ash, supposedly meets cute with her over adopting a dog from the shelter, but then confesses that she has read the blog and knows who Faith is. Faith is over the moon (but still not literally, because not flying), and we get a lot of detail on this relationship, hurt feelings from abandoned “regular” friends as she tours the lot and has milk shakes with the star, yadda yadda. Oh, and this is the point where Faith explores the idea that she might be gay…or bi? After all, in addition to the tempting Dakota there’s also her journalism swain, Johnny….

Enter third plot: Animals (both strays and pets), homeless people, and random teenage girls have disappeared from town and no one can find them. One dog and one girl reappear, but are catatonic and provide no clues to the mystery.

So how does all of this fit together? Badly. Improbably. Unconvincingly. Incompletely. Because…there may be a sequel in the works. Yeah. Which would actually be good if it clears up any of the picked up and dropped plot points, the fuzzy background and world-building, and Faith’s inexplicable reluctance to use her friggin’ superpower! But based on this one, I highly doubt it. I discovered on Goodreads that this is a prequel novelization of a superhero from Valiant Entertainment comics. If I were the author of those comics, I would not be happy at this moment.

Before I forget, allow me to address the fat girls in the room: Murphy punts in this book as she does in Dumplin’. She gives the heroine the possibility of a romance or two in which Faith speculates, “But what could they see in ME?” and she almost lets her have it, but then pulls back to deliver the same blow fat girls always endure, when they are told that they are not special and that no one would want them. Yeah, maybe that message served the plot at that particular moment, but aren’t we all tired of the incessant battering of that already bruised spot on the fragile fat-girl ego? I know I am.

I finished the book, but I confess that it was only so I could better skewer it. Faith herself is an ebullient and somewhat refreshing protagonist, but she’s so weighed down by a thin, chaotic and nonsensical story line that she’ll never, ever get off the ground.