2020 Faves

I don’t know if anyone is dying for a reprise of my favorite books of 2020. Since I am such an eclectic reader, I don’t always read the new stuff, or the popular stuff. Sometimes I discover something popular three years after everyone else already read it, as I did The Hate U Give this past January (it was released in 2017). Sometimes I find things that no one else has read that are unbelievably good, and I feel vindicated by my weird reading patterns when I am able to share it on my blog. But mostly I just read whatever takes my fancy, whenever it comes up and from whatever source, and readers of the blog have to put up with it.

Anyway, I thought I would do a short summary here of my favorite reads for the year, and since they are somewhat evenly populated between Young Adult and Adult books, I will divvy them up

that way.

YOUNG ADULT DISCOVERIES

Fantasy dominated here, as it commonly does, both because fantasy is big in YA and because I am a big fantasy fan. I discovered a stand-alone and two duologies this year, which was a nice break from the usual trilogy and I think worked better for the authors as well (so often the middle book is weak and the last book is rushed in those cases).

The first was The Hazel Wood and The Night Country, by Melissa Albert, and although I characterized them as fantasy, they are truthfully much closer to fairy tale. I say that advisedly with the caveat that this is not the determinedly nice Disney fairy tale, but a real, slightly horrifying portal story to a place that you may not, in the end, wish to visit! Both the story and the language are fantastic, in all senses of the word.

The stand-alone was Spinning Silver, by Naomi Novik. The book borrows a couple of basic concepts from “Rumpelstiltskin,” turns them completely on their heads, and goes on with a story nothing like that mean little tale. There are actual faerie in this book, but they have more to do with the fey creatures of Celtic lore than with any prosaic fairy godmother. It is a beautifully complex, character-driven story about agency, empathy, self-determination, and family that held my attention from beginning to end.

The second duology was The Merciful Crow and The Faithless Hawk, by Margaret Owen, and these were true fantasy, with complex world-building (formal castes in society, each of which has its own magical properties), and a protagonist from the bottom-most caste. It’s a compelling adventure featuring good against evil, hunters and hunted, choices, chance, and character. Don’t let the fact that it’s billed as YA stop you from reading it—anyone who likes a good saga should do so!

I also discovered a bunch of YA mainstream/realistic fiction written by an author I previously knew only for her fantasy. Brigid Kemmerer has published three books based on the fairy tale “Beauty and the Beast” (and they are well done), but the books of hers I fell for this year were about typical teenagers with problems that needed to be solved and love lives that needed to be resolved. My favorite of the four was Letters to the Lost, but I also greatly enjoyed More Than We Can Tell, Thicker Than Water, and Call it What You Want.

These were my five-star Young Adult books for 2020.

ADULT FICTION

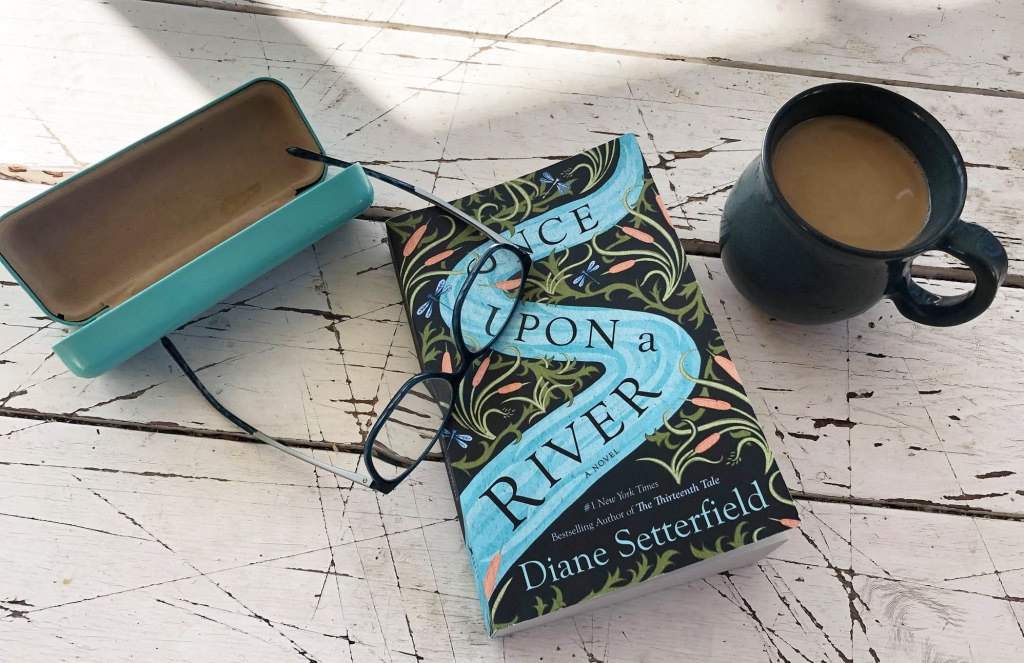

As YA selections were dominated by a particular genre, so were my books in Adult fiction, almost all of them falling in the mystery section. But before I give you that list, I will finish up with fairy tale by lauding an original adult story that engaged me from the first page and has stuck with me all year: Once Upon A River, by Diane Setterfield. The fairy tale quality is palpable but the archetypal nature of fairy tales doesn’t dominate the story, which is individual and unique. It is the story of three children and the impact of their disappearances (and possible reappearance) on the people close to them, as well as on the inhabitants of one small town beside the river Thames who are caught up by chance in the events that restore a child to life. But the story encompasses more than her fate: It gives extraordinary insight into the issues of life and death—how much they are worth, how they arrive, how they depart, and what is the best way to pursue them.

Another book I encountered in 2020 that didn’t fall into the mystery genre or belong to a series was the fascinating She Rides Shotgun, by Jordan Harper. This was a short, powerful book by a first-time author, a coming of age story set down in the middle of a dark thriller that bowled me over with its contradictory combination of evil deeds and poignant moments.

And the last stand-alone mainstream fiction novel I enjoyed enough to bestow five stars was Just Life, by Neil Abramson. The story showcases the eternal battle between fear and compassion, and involves a deadly virus and a dog shelter in a fast-paced, gripping narrative that takes over the lives of four people. It made me cry, three times.

Most of the mysteries I enjoyed this year came from a “stable” of staple authors I have developed over the decades and upon whom I rely for at least one good read per year. The first is Louise Penny, whose offering All the Devils Are Here in the ongoing Armand Gamache series is nuanced, perplexing, and utterly enjoyable, all the more so for being extracted from the usual Three Pines venue and transported to the magical city of Paris.

Sharon J. Bolton is a reliable source of both mystery and suspense, and she didn’t disappoint with The Split, a quirky story that takes place over the course of six weeks, in stuffy Cambridge, England, and remote Antarctica. Its main character, a glaciologist (she studies glaciers, and yes, it’s a thing) is in peril, and will go to the ends of the earth to escape it…but so, too, will her stalker, it seems. The Split is a twisty thriller abounding in misdirection, and definitely lives up to Bolton’s previous offerings.

Troubled Blood, by “Robert Galbraith,” aka J. K. Rowling, is my most recent favorite read, and is #5 in that author’s series about London private detective Cormoran Strike and his business partner, Robin Ellacott. It’s a police procedural with a lot of detail in service of both the mystery and the protagonists’ private lives, it’s 944 pages long, and I enjoyed every page.

Finally, this year i discovered two series that are new to me, completely different from one another but equally enjoyable.

The first is the Detective Constable Cat Kinsella series by Caz Frear, which currently encompasses three books. I read the first two earlier in the year and promptly put in a reserve at the library on the third (which had yet to be published at the time), and Shed No Tears just hit my Kindle a couple of days ago. They remind me a bit of Tana French, although not with the plethora of detail, and a bit of the abovementioned Sharon Bolton’s mystery series starring Lacey Flint. Cat is a nicely conflicted police officer who comes from a dodgy background and has to work hard to keep her personal and professional lives from impinging one upon the other, particularly when details of a case threaten to overlap the two. I anticipate continuing with this series of novels as quickly as Frear can turn them out.

The second, which is a mash-up of several genres, is Charlaine Harris’s new offering starring the body-guard/assassin Gunnie Rose. I read the first two books—An Easy Death and A Longer Fall—this year, and am eagerly anticipating #3, coming sometime in 2021 but not soon enough. The best description I can make of this series is a dystopian alternate history mystery with magic. If this leads you to want to know more, read my review, here.

These are the adult books I awarded five stars during 2020.

I hope you have enjoyed this survey of my year’s worth of best books. I am always happy to hear from any of you, and would love to know what you found most compelling this year. I think we all did a little extra reading as a result of more isolation than usual, and what better than to share our bounty with others?

Please comment, here or on Facebook, at https://www.facebook.com/thebookadept. Thanks for following my blog this year.

Predictable cheer

That was precisely what I was wanting, a few days before Christmas, considering that my “celebration” was going to be an hour on Zoom with my family instead of an in-person exchange of gifts followed by a sumptuous meal prepared by all of us. So I sought out the latest of Jenny Colgan’s books, #4 in her Mure Island series, conveniently just published in October of this year to be served up for holiday consolation.

I did enjoy it quite a lot. It included the regular cast of characters from Mure: Flora, owner of the only bakery/café on this tiny outpost in the middle of the ocean halfway between Scotland and Norway; Fintan, her gay brother, who has recently inherited “the Rock,” now re-christened the Island Hotel, from his recently deceased husband, the millionaire businessman Colton; and my personal favorite, Flora’s small but incredibly vocal niece, Agot, who is about five years old in this one.

The central activity of this book concerns the Christmas opening of the Island Hotel, and involves all the characters in the anxiety-producing activity of finding such essentials as a world-class chef who doesn’t mind living in such a remote corner of the north. Fintan, still grieving from the loss of his first and biggest love, isn’t much use, although he does manage to find and hire a rude and irritating but highly accomplished Frenchman; Flora, supposedly on maternity leave after giving birth to hers and Joel’s son, Douglas, is finding that Joel is better at motherhood and she is better at getting the hotel up and running, so despite massive feelings of guilt, that’s what she does.

But the central actors in this volume of Mure life are a shy employee from Flora’s Seaside Kitchen, the always-blushing and mostly silent Isla; and a new face to the island, Konstantin, a rich Norwegian playboy whose wealthy royal father exiles him to Mure (Joel has a hand in this, doing a favor for a friend of a friend) to work as a “pot boy” (dishwasher) in the kitchen of the new hotel. He’s never had a job, doesn’t know how to do anything, and thinks the world owes him a living, so to be cast ashore on this tiny island with no money, no phone, and no recourse is a major shock. But gradually he learns the pleasure of knowing how to do things, and his initial bad attitude dissolves as he makes friends with Isla (while hoping for something more), garners some hard-won praise from chef Gaspard, and begins to fit in on the island.

Although clichés abound, some of which were a little cringey, I would have enjoyed this fourth book in Colgan’s series pretty unreservedly except for several inconsistencies that couldn’t help but irritate: After three books featuring minor characters Charlie and his wife, Jan, who lead Outward Bound-type holidays for needy orphan boys on the island, Jan has suddenly been rechristened Pam; when she appeared in the story she seemed familiar, but I kept straining to remember, Who is Pam again? Likewise, the island doctor, Saif Hassan, in this book has the last name Hussein; and the main character’s partner, Joel, goes from Binder to Booker. What the hell, Jenny? Do you not even remember your memorable characters’ names? and do your editors not check these things? This is incredibly sloppy.

Overlooking those details, this was a fun read and a nice extension of the series. The ending was a bit sappy, but at Christmas, needs must.

Procedural, no police

I just finished reading Troubled Blood, the new Cormoran Strike novel by Robert Galbraith, aka J. K. Rowling. (I don’t know why she ever bothered to use a pseudonym, since she outs herself right on the first book cover flap, but whatever.) I’d almost like to make that statement (I finished!) twice or three times, because at 944 pages, this was a gargantuan achievement!

At that many pages, I also expected it to be an achievement that cost me some labor, and to be saying afterwards that she needs an editor—but I’m not going to do that. I loved the entire book. I didn’t find anything extraneous I wanted to cut.

I enjoyed reading it 40 or 50 pages at a time at the breakfast table or during my middle-of-the-night intermission from sleep, wherein I wake up and need to separate myself from my dreams, get a glass of water, and redirect my mind with good fiction, and I was reluctant to finish it.

Just to deal with this up front, there is absolutely no transgender character (or scandal) here. If you have heard that, you have been misinformed. In one instance, a killer puts on a wig and trenchcoat to disguise himself. That’s it. If you want to argue about this, go somewhere else. I’m tired of all the ugliness.

This book was such a wonderful adventure or exploration of all the ways two dedicated and stubborn people solve a mystery by following every lead, reading every note, re-interviewing anyone with any potential involvement, however small, and keeping their minds open and churning up ideas and solutions. It’s the first time that Cormoran Strike and Robin Ellacott have tackled a cold case, let alone one more than 40 years old, but their innate curiosity leads them down the path of one of the most fascinating mysteries they have ever encountered—the disappearance of Dr. Margot Bamborough. They are simultaneously tending to three or four other clients’ cases at the same time, aided by their contract hires Barclay and Morris, and organized by new secretary Pat; and their personal lives, both apart and together, are also on display. Robin is hoping that her unexpectedly acrimonious divorce from Matthew will conclude soon, while Strike is still dealing with the fallout from his ex-girlfriend Charlotte, who married someone else and gave birth to twins but still texts him wistful (and manipulative) messages in the middle of the night. And both of them are all too conscious of some significant moments they have shared that could mean more, if either of them chooses to act.

This is the ultimate in police procedurals, without having the police involved. Because of some good contacts, some clever thinking, and some helpful people, the detectives are able to get their hands on a good part of the police record, but the complication is that the original lead detective was suffering a mental breakdown while conducting the case, while his successor was more interested in devaluing everything his predecessor had done than in actually breaking new ground. So in some ways they are looking at the case not only with fresh eyes, but with attention to details that no one previous had seen in the same light.

As usual, Rowling also provides great side characters, who give both darkness and whimsy as their contribution to the main story she is telling. Robin’s relationship with Morris and Strike’s interactions with Pat, as well as the background of Cormoran’s family problems, provided great context and cushioning for the rest.

I don’t know what it was about this book—whether it was the book itself or simply the way I approached reading it, a little at a time rather than an all-out binge-fest—but I never got impatient with any red herring or tired of their continued speculations to one another about the various aspects. Part of it, of course, is the way Rowling writes the interactions between the partners, and the excruciatingly slow build she has given their relationship through multiple volumes that keeps you reading for any hint of a shift. There are some in this book, but I’m neither giving them away nor hinting at how extensive they might be. All I will say is that I felt completely satisfied by the resolution of the case, and that I have no doubt that the next chapter in the Cormoran-and-Robin show will be interesting!

It’s all Christmas

For those who want to use these last 10 days before Christmas to get themselves in the mood (or to dwell in a more traditional head space in the midst of this unquestionably nontraditional year), I thought I would remind readers of all the many holiday short stories, novellas, novels, and nonfiction offerings out there. I did a pretty comprehensive overview last year of a bunch of alternatives, so let me just give you those urls with a brief explanation and you can explore your options!

For a classic Christmas, check out this list of beloved read-alouds and come-back-tos:

Christmas classics

For a book-length experience, here are some novels and true-life experiences:

Novel Christmas

And for those who want something unsentimental, here are some that are a bit more tart than sweet:

Alternate Christmas

Finally, to hark back to a recent find, read Connie Willis’s latest Christmas offering:

Christmas joy

Have yourselves a lovely reading holiday, while I attempt to finish Troubled Blood in time to make it #130 on my Goodreads Challenge for 2020!

Christmas treats

I ended up taking a longer break than I had planned from the gigantic Cormoran Strike mystery (Troubled Blood) I thought was going to be occupying my week: I read with great enjoyment to page 152, whereupon my copy of the book started over again at page 121, went to 152 again, and then skipped to page 185! Two identical signatures followed by a missing one. True to signature sequencing, there were probably other errors later on, but I didn’t bother to find them, I just told Amazon to send me a new one tout de suite. But while I waited, I needed something to read.

People on “What should I read next?” have been asking for Christmas or holiday books to fill their Decembers with better stories than the real one in which they are isolated at home with Covid-19, and I have been suggesting that they read Jenny Colgan‘s half-dozen second books that are the Christmas stories attached to her regular novels. She has one for the Cupcake Café, one for the Little Beach Street Bakery, two for the Island of Mure, and two more attached to Rosie Hopkins’ Sweet Shop. The double gift here is that if you haven’t read the first, non-Christmas book, you can easily fill up your entire month of December by reading #1 and #2 of each of them, and then go on to round it out with the remaining sequels.

I myself had not read either of the Rosie Hopkins set that follow Welcome to Rosie Hopkins’ Sweet Shop of Dreams, mentioned here in last year’s wrap-up of Christmas reading, so while waiting on Amazon and Cormoran to get back to me, I picked up Christmas at Rosie Hopkins’ Sweet Shop. It begins shortly after the first book left off, and includes all the same characters with their relationships one to another and also to the Derbyshire village of Lipton, now buried under a blanket of snow unfamiliar to former city girl Rosie. We get to see the progression of Rosie’s relationship with new beau Stephen, her aunt Lilian’s adaptation to relocating from her cottage to the elder-care facility, and renew acquaintance with all the quirky (and otherwise) characters from the village. In addition, Rosie’s mother, brother, sister-in-law, and nephew/nieces descend from faraway Australia for the Christmas season. But just before they are about to arrive, a tragedy, with Stephen at its core, strikes in the village, and Rosie is so distracted and upset by current events that it promises to be a less than stellar Christmas. This is, however, a Jenny Colgan book, so you know that somehow joy will prevail. There are some surprises based on the pasts of a couple of the characters, and all in all it’s a satisfying story arc.

Having gotten into this holiday mood, I decided (despite the arrival on the front porch of my replacement book) to continue by reading The Christmas Surprise, the third book in this group—which actually begins a couple of weeks after Christmas. Who knows, Cormoran and Robin may have to wait until January at this rate. Which may be good for my Goodreads challenge, since I can get in three books for the “price” of one by pursuing all the Colgans instead of the single volume of 944 pages offered by Rowling, er, Galbraith!

We’ll see what happens.

Christmas joy

True to my prediction, I took a small break between the gargantuan novels awaiting my attention (just finished Addie LaRue at 442 pages, and embarking next on Troubled Blood,

at 944!) to read a small but delightful Christmas story. I knew that Connie Willis collected such stories, having come across a comprehensive list she made some years ago of all her can’t-miss favorites, but I didn’t know she had written one,

until now.

Take a Look at the Five and Ten is pure nostalgia in its subject matter while being scientific in its methodology. It adopts the premise of her book Passage, wherein a neuroscientist is conducting research on a particular aspect of memory. In that book it’s all about dreams, while in this one the topic is the TFBM: Traumatic Flashbulb Moment. A Ph.D. student, Lassiter, is doing a study of people who have experienced one of these; imagine his delight when he meets a new and potentially perfect subject at Christmas dinner with his new girlfriend’s family.

Ori begins dreading each year’s holiday season (Thanksgiving to New Year’s Day) in July. Her one-time stepfather, Dave, never lets go of the people from his past, so even though he’s working on his sixth marriage (his union with Ori’s mom ended when she was eight years old)), he never forgets to include in his celebratory invitations the in-laws he collected along the way, including Ori, Aunt Mildred (the great-aunt of his second wife), and Grandma Elving (the grandmother of his fourth). Dave’s latest bride, Jillian, cooks elaborately awful trendy food, and invites her snotty daughter Sloane, along with Sloane’s current boyfriend and her own stuck-up friends, and they all, with the exception of Grandma Elving, treat Ori as if she is a combination of charity case and the hired help.

Grandma Elving presents her own trying behavior, as she insists on telling the same story each year of how she worked at F. W. Woolworth’s “five and dime” store in downtown Denver one Christmas in the 1950s. Everyone else in the family is fed up to the gills with hearing it, but Sloane’s new boyfriend is fascinated by Grandma’s extraordinary ability to remember each and every vivid detail about her experiences at Woolworth’s, since clarity and consistency of a particular memory are hallmarks of a TFBM. Lassiter invites Grandma to be one of his test subjects, and the two of them elicit assistance from Ori to get Grandma to and from her appointments at the clinic where Lassiter is conducting the experiment. Ori quickly begins to have what she knows are ill-fated feelings for Lassiter as their proximity grows….

This is a cute and humorous Christmas tale reminiscent of the French farce-like quality of Willis’s time-travel book, To Say Nothing of the Dog. It’s short (140 pages), qualifying more as a novella than a full-length book, and you can get it for Kindle too, so if you’re trying to hit your 2020 Goodreads Challenge quota, it’s a quick read that counts. But best of all, it’s an unconventional Christmas story that will give you even more appreciation for Willis’s whimsy and heart.

Addie! Addie!

There has been a lot of anticipation leading up to the publication of The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue, by V. E. (Victoria) Schwab, not the least of which was following Schwab on her Facebook page as she agonized over the completion of the manuscript and talked about how much this book (10 years in the making) meant to her. It made me almost afraid to read it, despite the fact that I adore her book Vicious (read it three times, won’t be the last) and her “Shades of London” fantasy series. I have found with this author that I have unreservedly loved everything she has written for adults, while the stuff she wrote for teens (The Archived, Monsters of Verity) has pretty much left me unsatisfied. Since it’s hard to say where this book should fall—the protagonist is, after all, a young woman in her early 20s—I really didn’t know what to expect.

The other weird experience has been watching it grow in popularity because of its presence on the New York Times hardcover fiction bestseller list. That list is usually dominated by a combination of popular genre authors (Michael Connelly, Nora Roberts), and so-called “realistic” or “mainstream” fiction, so to have a fantasy entry such as this sitting at #14 is not the norm. I have watched, bemused, as the “What Should I Read Next?” group on Facebook started buzzing, asking each other, “What is this Addie LaRue book? Is it good? Should I read it?” Since their common fare is a combo of suspense fiction and books like A Man Called Ove and Where the Crawdads Sing, I am fascinated to see what they make of Ms. Schwab’s latest offering.

Adeline is a dreamer. She begins in the small French village of Villon, born in 1691 and expected to grow up as other girls do, to do her duty—to marry, to have children of her own, to die. But at 16, when the villagers are looking at her as a bloom ready for plucking, she feels like the world should be getting larger instead of tightening like chains around her body.

“She is at odds with everything, she does not fit, an insult to her sex, a stubborn child in a woman’s form, her head bowed and arms wrapped tight around her drawing pad as if it were a door. And when she does look up, her gaze always goes to the edge of town.”

At 23, having managed to avoid commitment for another seven years, she is unexpectedly trapped by the will of her parents, who gift her “like a prize sow” to a widower with three small children. She numbly goes along, dons the dress, gets ready for the inevitable and then, like more brides than you would believe, she runs. And after she has run, she prays to the gods for an alternative. She has forgotten, however, that it is unwise to pray to the gods that answer after dark. She asks to live. She asks to be free. She asks for more time. She promises her soul. The god grants her wish to be “untethered” in return for a promise that he can have her soul when she doesn’t want it any more. She should have known there was a greater price, but she made the deal. And with that promise she was doomed to eternal anonymity, to pass through the world without making a mark. She is the literal embodiment of “out of sight, out of mind.” Then, after nearly 300 years, someone speaks to her the fateful, blessed words: “I remember you.”

This is not, as some people might expect, a sweeping historical saga. Its goal is not to illuminate the time periods through which Addie lives, but rather to mark the poignant encounters through which her life briefly touches others. Although there is a rich cast of characters, there are only three who matter; but this is definitely a character-driven story, based on the relationship of a god to two humans whose test is melancholy and loss of hope versus the power of sheer stubbornness and the love of beauty and art. The story takes shape slowly, in a past-and-present format of Addie’s beginnings and her circumstances in present-day New York City. There is, admittedly, a lot of navel-gazing on the part of at least two of the characters, but it serves the themes of the book, which echo through your head with a resounding consonance.

I found some of the language almost too flowery; but given that what sustains Addie in her continued existence is the unexpected joy of words, art, nature, and novelty, I couldn’t fault the author for the fact that her prose was a little purple.

It’s tempting to go on here and talk about what was effective in her two relationships, one with the god and one with the man who sees her; but I think it’s more important to preserve at least that much of the mystery and let other readers discover those effects for themselves.

One thought that comes to mind, having read and appreciated the ending, is that this entire book could, in one way, be summarized by saying “It’s all about semantics.” As a person who is extremely conscious of language, I found that idea delightful.

As Neil Gaiman said in his cover quote for Victoria, “For someone damned to be forgettable, Addie LaRue is a most delightfully unforgettable character, and her story is a joyous evocation of unlikely immortality.” Pick up the book and see if you agree.

Between the “greats”

I follow a lot of authors and anticipate their books and then, paradoxically, when they come out I take my time about getting around to reading them. I think it is a defense mechanism—equal parts fear that they won’t be as good as I have anticipated, or that they will be as good but that they will take me a lot of time and energy to get through and then think about and analyze. Sometimes, after all, you want a reading experience that is not intense, that is not taxing, that takes you somewhere familiar and allows you to follow along somewhat passively instead of being an active reader.

I have been in that exact place, during the past two weeks. I had a choice between reading Return of the Thief, “the thrilling, 20-years-in-the-making conclusion to the New York Times–bestselling Queen’s Thief series, by Megan Whalen Turner,” which is one of my favorite fantasy series of all time; Troubled Blood, the next in the exciting and engaging Cormoran Strike private detective series by alias J. K. Rowling; or V. E. Schwab’s brand-new book The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue, which is already making waves on all the best-of book lists out there. Thief and Addie are close to 500 pages apiece, while Rowling has done her usual of increasing the page-count of the book with each addition to the series, this one coming in at a whopping 944! So taking on any one of them won’t be a short-term experience, and deciding which to prefer above the others is also all locked up with my feelings towards each. Do I really want my favorite series to end?

Will these books live up to the others? Is the hype bigger than the book?

My response, this past week, was to turn aside from all three of them and pick up an early entry in Lee Child’s Jack Reacher series, The Enemy. After I got about a third of the way into it, some vaguely familiar scenes made me go check Goodreads, whence I discovered that I had actually read this book before; but it was more than five years ago, I have read at least 400 books (maybe more) in the intervening years and, despite certain scenes jiving with my memory, I didn’t remember anything about how it resolved.

As some readers of my blog will remember, I swore off of more Reacher books after reading the latest one, which was dark and ugly and didn’t feature the Reacher we had all come to know and respect for so many years and volumes. But this one is not only early in the series (#8), it’s also a flashback to when Reacher was still in the military working as an active police major (M.P.), solving crimes from within the confines of rules and protocol.

It begins on New Year’s Eve 1989, when Reacher is still in the army and has inexplicably been transferred from Panama to Fort Bird, North Carolina. Everyone else is out celebrating the turn of the decade, but Reacher is on duty when a two-star general is found dead in a sleazy motel 30 miles from the base, and it looks like he wasn’t alone. It’s the classic case of heart attack in the midst of sex but, by the time Reacher arrives, the hooker is no longer on the scene, nor is the general’s briefcase. Reacher’s new boss at Bird tells him to “contain the situation” so that the army won’t be embarrassed, but when Reacher goes to deliver the news of the general’s death to his widow in Virginia, the widow turns up dead too, and speculation about the contents of the briefcase suddenly turns the affair into something more complicated. Reacher recruits a (female) M.P. named Summer to help him run down all the details, and the two of them go ever deeper into danger as they defy the military to dig into this broadening potential scandal.

The book is a convoluted, intriguing puzzle from start to the very last page. There is a quote on the cover of my paperback from the Chicago Sun-Times that calls it “a thriller that gallops at a breakneck pace.” This proves that no one at that newspaper actually read the book; while it is, indeed, thrilling at certain points, and Reacher and Summer travel extensively across the States and into Europe during a 10-day period, spending as little as eight hours at some destinations, the pacing of this book is deliberate and every detail is noted, from what the protagonists are wearing down to how many cups of coffee they consume during breakfast at the Officers’ Club. In order to appreciate Reacher, you have to dwell in the details, because you never know when one will become significant.

This was a good one, and bravo to Lee Child for writing this background story so successfully.

As for making a decision between the three alternatives I mentioned at the top of this blog post, I think the safest is probably the stand-alone book in which I don’t have quite as much invested, so Addie LaRue will be my next read. Unless I put them all off to do some theme reading for the holidays, such as Jenny Colgan’s Christmas at the Cupcake Café? It’s entirely possible…

And a timely sequel

I previously enthused here about The Merciful Crow, by Margaret Owen, and mentioned how excited I was to move on to the sequel, The Faithless Hawk. I picked that book up this week, and right away discovered two things I liked about it:

- It continued to be timely, in the same weird way as was the first book, as far as its association with current events is concerned;

- Although I had thought (I think because of the title of #2, which didn’t seem to indicate finality) that this was going to be a trilogy, it turned out to be a duology, complete in two books. I wouldn’t have minded reading more about these characters, but the second book was as tightly and dramatically written as the first, and you couldn’t ask for a better wrap-up. Since so many times a trilogy turns out to have either a weak second book or a rushed-to-be-completed third one, I was satisfied and happy with the arc of this two-book story.

The second book picks up about a month after the first one left off; Fie’s troop of Crows are still on the road, and they’re taking her Pa to a Crow way station, which is the equivalent of retirement. He will live there and provide safety and supplies for all Crow troops who seek sanctuary. While at his designated way station, Fie meets with an enigmatic caretaker who is supposed to be the contemporary stand-in for the mythical god “Little Witness.” But to Fie’s surprise, awe, and unease, the person she meets is the actual Little Witness, and she hints things to Fie about her past and her future that are truly disquieting. One of them is that Fie has not yet fulfilled her contract with the Covenant, which she thought she had met by saving Prince Jasimir and bringing him to the General who is keeping him safe while championing his cause. But apparently Fie’s indebtedness to the Covenant goes back many lifetimes and is, in fact, the reason why the Crows roam friendless on the roads.

Just when Fie is absorbing all of this, she and her troop learn of the death of the king, Surimir, by Plague, and they decide to make their way to the Prince, who is with General Draga and her son Tavin, Fie’s love (and the Hawk of the title). A short time after they reunite, however, they are all thrown into dismay and confusion by the machinations of Queen Rhusana, who will do anything to ascend the throne. Once again Fie realizes that the fate of the kingdom may rest on her unready but stubborn shoulders.

In The Merciful Crow, the focus was much more on the journey (both physical and metaphorical) made by Prince Jasimir, Fie, and Tavin, discovering more about the current situation of the kingdom and about each other, and specifically cultivating the romance between Tavin and Fie. By comparison, The Faithless Hawk focuses on a bigger picture: the system of magic, the history of the various castes’ birthrights, and politics in general. This book really fleshed out the world-building, but it didn’t neglect its characters; we also get to learn more about Fie and start to fathom why she is such a central character to this conflict.

The content I mentioned at the top of this review—about its being timely and in synch with current events—has to do with the examination of the entire system of governance, caste, and society. One character remarks,

“We made a society where the monarchs could ignore the suffering of their people because it was nothing but an inconvenience, and we punished those who used their position to speak out.”

I don’t want to give away the entire plot here, but a seminal part of this story is how the characters come to realize that if this world is going to work for everyone, simply substituting a new ruler at the pinnacle of the government probably won’t serve. The rules and systems need to be examined, and must adapt, change, or be abolished in order to make things safe for all people going forward. In The Faithless Hawk, it takes the predations of an unexpectedly corrupt ruler and the threat of a worldwide plague to make that plain.

Some trigger warnings about this duology: There are seriously gory, disgusting scenes with realistic and thorough descriptions of what has occurred; and the use of teeth in their form of magic/wizardry is creepy/troubling (especially to those of us with dental anxiety to begin with). But the books are well worth a few squeamish moments for their powerful portrayals. I hope this immersive fantasy gets the attention

it deserves.