News re: my dog

At the center of When Will There Be Good News, Kate Atkinson’s third Jackson Brodie novel, is a new character, Reggie. I enjoyed this book mainly because I so adored her. She is 16 (sweartogod), looks 12, acts 36, and is an old soul and a compassionate but completely pragmatic one. Best teenager in fiction for a while now.

At the center of When Will There Be Good News, Kate Atkinson’s third Jackson Brodie novel, is a new character, Reggie. I enjoyed this book mainly because I so adored her. She is 16 (sweartogod), looks 12, acts 36, and is an old soul and a compassionate but completely pragmatic one. Best teenager in fiction for a while now.

While I found the multiple story lines of Dr. Joanna Hunter, whose family members were all inexplicably knifed to death in the middle of a field one day when she was a child, Joanna’s husband’s questionable business practices, Chief Inspector Louise Monroe’s domestic violence case, and the almost incidental appearance of Jackson Brodie (who is in-country for personal reasons and yet by a twist of fate ends up plumped down in the middle of all of these mysteries) all to be interesting, it isn’t until they get connected by Reggie that things really get going, even though she, like Brodie, is involved almost despite herself. The brief period when Louise, Jackson, and Reggie are all in the same room at the same time is my favorite scene in the book.

These books of Atkinson’s are so…perverse! Not in a sexual way, let me hasten to add, but in the sense that they are “contrary to the accepted or expected standard or practice.” You can’t actually call them mystery novels. I mean, there ARE mysteries, and many of them do get solved, but they are practically beside the point. The books are character studies, and there are few who are able to delineate a character as well as Kate Atkinson.

While I find these books frustrating in the way they meander off the beaten path and into prolonged ponderings about this or that (not to mention all the stream-of-consciousness literary references that keep popping up in Brodie’s dragonfly mind), the stories are always resurrected by the strength of the characters themselves.

Because of that trait, I think I may have liked Started Early, Took My Dog the best so far of the Jackson Brodie books, although Jackson’s role in it is mostly ridiculous! The central mystery is set in Northern Yorkshire, where Jackson is trying to track down the birth parents of a client who was adopted in England at age two and then taken to New Zealand to grow up. But when Jackson discovers someone he thinks might have been the birth mother, a murder case from 1975 causes all kinds of people to come out of the woodwork to prevent the truth about police corruption and misbehavior from coming out.

Because of that trait, I think I may have liked Started Early, Took My Dog the best so far of the Jackson Brodie books, although Jackson’s role in it is mostly ridiculous! The central mystery is set in Northern Yorkshire, where Jackson is trying to track down the birth parents of a client who was adopted in England at age two and then taken to New Zealand to grow up. But when Jackson discovers someone he thinks might have been the birth mother, a murder case from 1975 causes all kinds of people to come out of the woodwork to prevent the truth about police corruption and misbehavior from coming out.

The title of the book turns out to be a double entendre, since taking a dog away from his abusive master (literally beating the guy up after he takes out his ill temper on his dog by berating it and kicking it in the ribs) is one of Jackson’s more rational moments in the book.

In addition to the dog-napping (I always thought that should be nabbing, not napping), there is child-napping, and they are both accomplished by former police officers! Tracy Waterhouse, just retired from the force, working part-time as a mall security guard, and supposedly resigned to or even content with her single, childless existence, sees a prostitute dragging her small child through the shopping center while screaming at her, and snaps. She has money in her pocket intended for the Polish bloke remodeling her kitchen, but instead hands it off to Kelly Cross in exchange for her youngest child. Suddenly, Tracy has stepped from one side of the law to the other.

But IS Courtney the daughter of Kelly Cross? Tracy wonders. At first she thinks she’s simply being paranoid, but then she realizes that there are all sorts of people trying to “get in touch” who may have been sent to take Courtney back. Meanwhile, Jackson is, weirdly, encountering the same folks who are after Tracy, none of whom have either his quest or his best interests at heart.

Throw in other seemingly random characters whose histories and futures are tangled up somehow with these two, and things get truly confusing. It’s no wonder that the one piece of dialogue our Mr. Brodie repeats throughout the book is “I don’t understand.” It paints a pretty ineffectual picture of him as a private investigator, but certain leads to some interesting situations.

I liked this best mostly because of the characters of Tracy and Courtney. Tracy is large, awkward, stalwart, and ultimately heroic, while Courtney delights as only a truly quirky small child can. Between the two of them, they carry the story.

“Dragon,” courtesy of KJ Allison

As with the other Jackson Brodie books, the point is less about the mysteries and more about human themes of loneliness, grief, and dysfunction. Practically every character (except the determinedly upbeat Judith) is damaged and in need of love and/or salvation. Even the minor characters—Tracy’s colleague Barry, the aging actress Tilly—bring pathos to the story. And yet there is also humor, especially in the way Jackson’s role seems that of a character in a French farce, doomed to make his entrance from stage left just as his quarry (or his explanation) is departing from stage right.

I really hope that Atkinson plans to reveal the answers to some major cliffhangers left dangling off the edge at the end of this one: Who is Courtney, really? What was Jackson up to before he took on this case? Who is the murderer of a rather significant character? And I’m still waiting for the other shoe to drop with Louise, three books later. C’mon, Kate, resolution!

The Dry

After reading The Lost Man and being bowled over by it, I couldn’t resist moving on to Jane Harper’s other books, starting with her first, The Dry.

While this debut novel is more of a police procedural and less of an epic saga than The Lost Man, Harper doesn’t miss out on using the landscape as a big influencer on the townsfolk of Kiewarra. The sun blazes down, the blowflies hover, the river has dried up, and along with it have gone the fortunes of the farmers in this rural Australian community. The burning heat of the drought ratchets up the tension amongst everyone who lives there, and turns an already small-minded bunch into something mean.

While this debut novel is more of a police procedural and less of an epic saga than The Lost Man, Harper doesn’t miss out on using the landscape as a big influencer on the townsfolk of Kiewarra. The sun blazes down, the blowflies hover, the river has dried up, and along with it have gone the fortunes of the farmers in this rural Australian community. The burning heat of the drought ratchets up the tension amongst everyone who lives there, and turns an already small-minded bunch into something mean.

A tragedy seemingly caused by this unbearable strain is the vehicle that brings Aaron Falk back to his adolescent home, 20 years after he and his father were driven away. Falk’s best childhood friend, golden boy Luke Hadler, is dead; he has apparently taken a shotgun and murdered his wife and young son, then turned the gun on himself. If Falk, now a forensic accountant, had his druthers, he would have sent flowers and stayed the width of the continent away from Kiewarra; but Luke’s parents beg him to come, and Luke’s father adds a cryptic note that causes Falk to panic just a little. This is not the first person Aaron has lost from this town, and despite a finding of suicide, the persistent suspicions cast on him after his friend Ellie Deacon’s death when they were 16 are what caused him to leave in the first place.

Despite significant opposition from the townspeople who hate him, Falk joins forces with the new cop in town, Sergeant Raco, who has had his own suspicions about how the Hadlers actually died but hasn’t gotten anywhere with them. Together he and Aaron begin to uncover the lies that were told, the secrets that have been kept, and the fears and assumptions that are slowly turning Kiewarra into a powder keg.

This was an excellently written mystery, with completely believable red herrings and a truly unexpected resolution. The element that carries it over the top is the attention to detail in both the characterization and the atmosphere. You know these people, and you feel their emotions; you learn this place and you feel its desolation. The narrative carries you along, moving seamlessly from Falk’s past with Luke, Ellie, Gretchen, and the townspeople who constantly have their eye on these teenagers into the present where everyone (except Ellie) has grown up and into themselves, for better or worse (mostly worse) and are all re-engaging over this new tragedy. A stunningly well-done piece of investigative fiction that might appeal to the readers of Craig Johnson’s Walt Longmire books.

Novel Christmas

For those who appreciate a lengthier read, I have attempted to round up some novels with Christmas themes or settings and, in doing so, not make you doubt my good taste!

For ’tis true, ’tis true that a plethora of Christmas tales exist, but whether you want to read any of them is the question. I have, therefore, found a few I would consider a bit more literary, and a bunch that are connected to some genre series, since much may be forgiven your favorite authors when they sell out, er, decide to delight you with a Christmas-related chapter.

For ’tis true, ’tis true that a plethora of Christmas tales exist, but whether you want to read any of them is the question. I have, therefore, found a few I would consider a bit more literary, and a bunch that are connected to some genre series, since much may be forgiven your favorite authors when they sell out, er, decide to delight you with a Christmas-related chapter.

First off, consider two short, sparkling comedies set at Christmas-time by Nancy Mitford, the writer later known for Love in a Cold Climate. Christmas Pudding and Pigeon Pie are Oscar Wilde-ish “great house” stories with a cast of ridiculous upper-crust characters rivaled only by those depicted by E. F. Benson and P. G. Wodehouse.

Next, there’s Wishin’ and Hopin’, a Christmas story by Wally Lamb, which focuses on a feisty parochial school boy named Felix Funicello—a distant cousin of the iconic Annette.

In a similar humorous vein, check out comedian Dave Barry’s The Shepherd, the Angel, and Walter the Christmas Miracle Dog. Or, on a more sympathetic note, Frank McCourt’s Angela and the Baby Jesus, relating the story of when his mother Angela was six years old and felt sorry for the Baby Jesus, out in the cold in the Christmas crib at St. Joseph’s Church….

The Christmas Train, by David Baldacci, is not a book I have read, but it sounds like a perfect storm of circumstances guaranteed to be entertaining, landing a former journalist on a train over the Christmas holidays with his current girlfriend, his former love, and a sneak thief, all headed towards an avalanche in the midst of an historic blizzard.

Skipping Christmas, by John Grisham, follows the fate of Luther and Nora Krank, who decide that, just this once, they will forego the tree-trimming, the annual Christmas Eve bash, and the fruitcakes in favor of a Caribbean cruise.

One of my personal favorites to re-read this time of year is Winter Solstice, by Rosamunde Pilcher. It is sentimental without being mawkish, and brings together an unusual cast of characters in an interesting situation bound to produce results.

One of my personal favorites to re-read this time of year is Winter Solstice, by Rosamunde Pilcher. It is sentimental without being mawkish, and brings together an unusual cast of characters in an interesting situation bound to produce results.

Now we enter the realm of franchise genre fare with a nod to Christmas:

The Christmas Scorpion is a Jack Reacher story (e-book only) by Lee Child, in which Jack’s intention to spend the holidays in warm temperatures surrounded by the palm trees of California somehow lands him instead in the midst of a blizzard facing a threat from the world’s deadliest assassin.

There are many in the mystery category, from Agatha Christie to Murder Club to baked goods-filled cozies:

In Hercule Poirot’s Christmas, by Agatha Christie, a curmudgeonly father turns up dead after telling all four of his sons, home for Christmas, that he is cutting off their allowances and changing his will. Poirot suspends his own festivities to solve the murder.

James Patterson has a couple of entries: The 19th Christmas, a Women’s Murder Club book, and Merry Christmas, Alex Cross, starring his popular detective trying to make it back alive for the most sacred of family days.

Charlaine Harris’s unconventional pseudo-cozy series about housekeeper and body builder Lily Bard features Shakespeare’s Christmas, in which Lily solves a four-year-old kidnapping case while at home for her sister’s Christmas wedding.

In a similar manner (though with quite different affect!), Rhys Bowen’s Irish lass Molly Murphy attends an elegant house party at a mansion on the Hudson in The Ghost of Christmas Past, and tries to fathom the reappearance of a girl who disappeared 10 years ago.

Anne Perry, known for her historical fiction featuring the Pitts (Charlotte and Thomas) and the rather darker William Monk, has written 16 Victorian Christmas mysteries to date, the latest being A Christmas Revelation (2018).

Anne Perry, known for her historical fiction featuring the Pitts (Charlotte and Thomas) and the rather darker William Monk, has written 16 Victorian Christmas mysteries to date, the latest being A Christmas Revelation (2018).

Cozy mystery writer and baker Joanne Fluke has written at least four full-length books plus some short stories enticingly evoking Christmas cake, sugar cookies, plum pudding, candy canes, and gingerbread cookies, all with the word “Murder” appended.

And Ellen Byron continues her hijinks in Bayou country with Maggie Crozat in A Cajun Christmas Killing, complete with recipes.

In the Western genre, you can find A Colorado Christmas, by William W. and J. A. Johnstone, in which one family’s Christmas gathering turns into a gunslinging fight for survival, and A Lawman’s Christmas, by Linda Lael Miller, a combination of love story and western set in 1900s Blue River, Texas.

One writer of whom I am fond, in the “relationship fiction” category, is Jenny Colgan, and she has made the most of her Christmas opportunities. The only problem with them is, each and every one is a sequel to one of her other books, so without reading the first, you will be somewhat lost inside the Christmas special. She has written four “Christmas at” or “Christmas on” books to date, set in the previously detailed locales of Rosie Hopkins’ Sweetshop, the Cupcake Café, the Island, and the Little Beach Street Bakery. But if you want some enjoyable, lighthearted fare a step beyond a simple romance, you may want to read the first books and come back for the Christmas ones.

In straightforward and utterly enjoyable chick lit, we have Christmas Shopaholic, by Sophie Kinsella, an ode to shopping with a Christmas theme for her popular heroine, Becky Bloomwood Brandon.

And then we hit the high tower of paperbacks that is the romance genre. I’m not even going to try to name all the books written within the environs of romance series, I’ll just give you a list of authors, and if you see a familiar one, go look her up on Goodreads with the word “Christmas” appended to her name:

And then we hit the high tower of paperbacks that is the romance genre. I’m not even going to try to name all the books written within the environs of romance series, I’ll just give you a list of authors, and if you see a familiar one, go look her up on Goodreads with the word “Christmas” appended to her name:

Mary Kay Andrews, Jennifer Chiaverini, Janet Dailey, Johanna Lindsey, Debbie Macomber, Fern Michaels, Linda Lael Miller, Phyllis Reynolds Naylor, Nancy Thayer, Sherryl Woods…and so on. There are PAGES of titles.

Finally, if you are a nonfiction kinda person, I’m tagging on a couple for you, too:

In I’m Dreaming of a Black Christmas, comedian Lewis Black says humbug to everything that makes Christmas memorable, in his own engaging, curmudgeonly style.

In their quest to provide mathematical proof for the existence of Santa, the authors of The Indisputable Existence of Santa Claus: The Mathematics of Christmas, by Dr. Hannah Fry and Dr. Thomas Oléron Evans painstakingly analyze every activity, from wrapping presents to cooking a turkey to setting up a mathematically perfect Secret Santa. Lighthearted and diverting, with Christmassy diagrams, sketches and graphs, Markov chains, and matrices.

If you can’t find something to read and enjoy from THIS list, I wish you a slightly exasperated Joyous Yule, and hope to find you something non-holiday-related to read in the New Year! —The Book Adept

Lost

Someone recommended Jane Harper to me as an author I might enjoy, so on my last virtual library visit, I downloaded The Lost Man to my Kindle. I forgot it was there and read other things, then realized I only had seven days left before it disappeared back into the library catalogue, so I put aside the Christmas-themed stuff for a minute and started it at 3 a.m. on Monday.

To quote another reviewer on Goodreads, this is less a novel and more an experience in which you lose yourself. And when you read it unencumbered by expectations, the power of its prose jumps out at you and grabs every bit of your attention.

The landscape, the Queensland (Australia) outback, is the most powerful character in the story. The landscape pares people down into either the essence or the caricature of themselves. Setting a mystery there is like creating a locked room puzzle (once you get in, there appears to be no way out), except that the room is an endless, airless, boiling plain of sand. The setting has dictated the style and pacing—spare, dry, concentrated.

The characters, three brothers, run livestock on land that, while adjacent to each other’s holdings, is hours apart in travel time, from each other and from “town.” Nathan Bright, the eldest and the protagonist, works alone and lives alone on his land (a backhanded gift from his former father-in-law), a scandal in his past making him a pariah with everyone but his family, and uncomfortable even with them. Divorced and bitterly intent on prying some form of joint custody of his son, Xander, from his ex-wife, Nathan is inturned and enigmatic. Cameron, the middle son, a “hail fellow well met” type, and “Bub,” the youngest brother, a bit lost in the shuffle and wishing for other options, live and work together on their father’s former holdings, with Cameron’s wife and two children, the boys’ widowed mother, and various stockmen and itinerant workers.

The characters, three brothers, run livestock on land that, while adjacent to each other’s holdings, is hours apart in travel time, from each other and from “town.” Nathan Bright, the eldest and the protagonist, works alone and lives alone on his land (a backhanded gift from his former father-in-law), a scandal in his past making him a pariah with everyone but his family, and uncomfortable even with them. Divorced and bitterly intent on prying some form of joint custody of his son, Xander, from his ex-wife, Nathan is inturned and enigmatic. Cameron, the middle son, a “hail fellow well met” type, and “Bub,” the youngest brother, a bit lost in the shuffle and wishing for other options, live and work together on their father’s former holdings, with Cameron’s wife and two children, the boys’ widowed mother, and various stockmen and itinerant workers.

At the beginning of the story, there is a small gathering at the stockman’s grave, a landmark headstone out in the middle of nowhere, so old that no one remembers who is buried there. Various legends remain about this eerie place, and it’s about to acquire one more: Cameron’s body has just been discovered in the slight shade cast by the stone.

Questions abound: How did he get there? Something had been troubling him—did he choose to meet his death by this unpleasant method? This is the premise of local law enforcement, and also of most of those who knew him…because if he didn’t, then the incredible isolation in which these people live leaves room for only a few suspects. The questions begin to prey on Nathan’s mind….

The mood and the tone of this book fascinated me. The characters remain enigmas for much of the story, their demeanors an exercise in taciturnity. Even the children are opaque. Likewise, the stark factors of living in the outback—reminding yourself to drink 10 times a day, attending the School of the Air via radio because the closest “local” school is 20 hours away in Brisbane, never leaving the property without noting down your destination and the expected time of return so a search party can be sent out if you miss your mark…all speak to a daily tension already so high that adding any sort of drama to it could spark a wildfire.

If you enjoy inhabiting an environment nothing like your own and learning what kinds of people are challenged by it to make a life there, this book will pull you in. If you are fascinated by the interplay of emotions between characters who have known each other forever and yet now doubt they know anything at all, this book will keep you guessing. Slow pacing and immaculate plotting give you questions and doubts just as the characters arrive at those same thoughts. It’s an emotionally charged but quietly told story that is probably my favorite read of 2019.

READERS’ ADVISORY NOTES: I’m trying to dredge up from my subconscious some other books that might share the appeals of this one. Perhaps The Road, by Cormac McCarthy, although it is such a stylized kind of work compared to this…. The River, by Peter Heller, has certain similarities. Maybe The Round House, by Louise Erdrich? or Bluebird Bluebird, by Attica Locke? The Lost Man gives me sort of the same feeling as reading “King Lear,” with the twisted family dynamics, the ugly lies and truths, the suspicions and doubts and manipulations.

One good turn

Can you be simultaneously enthralled with and utterly bewildered by the same book, the same author? If you read Kate Atkinson’s Jackson Brodie books, the answer is yes.

I reviewed Case Histories, her first book starring Brodie, a month or so back, and noted at the time that while I felt like Brodie was a great anchor for the three disparate cold cases being explored in that book, the mysteries were composed of equal parts frustration and intrigue. Little did I know the foreshadowing in which I was participating when I assayed to read the second Brodie book, One Good Turn.

I reviewed Case Histories, her first book starring Brodie, a month or so back, and noted at the time that while I felt like Brodie was a great anchor for the three disparate cold cases being explored in that book, the mysteries were composed of equal parts frustration and intrigue. Little did I know the foreshadowing in which I was participating when I assayed to read the second Brodie book, One Good Turn.

In this book, Jackson is even less involved, in some ways, than in the last; he isn’t hired by anyone to do anything until more than two-thirds of the way through. For most of it, he is a hapless bystander forced into participation by circumstance, as are the other four (six? it’s hard to say) significant characters. You almost couldn’t call this “his” story, except peripherally.

The setting is the Edinburgh Festival (Fringe?), and Jackson is there to support his girlfriend, Julia, an actress appearing in an existential play in a grotty venue on an unappealing street at the heart of the city. He is not entirely comfortable in this mostly passive tag-along role, and in fact has been uncomfortable in general for some time—ever since he inherited big money from one of his clients and retired from his private detective gig to buy a villa in France. He feels at loose ends wherever he is, although being with Julia at least puts him in a committed relationship. He still reacts like a policeman, and is hard pressed not to act like one when the opportunity arises, as it eventually does in this book.

First, though, we meet the other significant protagonists in this crazy casserole of a story, who are on parallel tracks that converge at unexpected intersections as the book unfolds. There is Martin, a meek and reclusive writer of cosy mystery novels, who uncharacteristically intervenes in a road rage incident and is caught up in undesirable relationships with victims, perpetrators, and bystanders as a result; there is Gloria, whose dicey husband is in a coma after a night with a Russian prostitute; and there is Louise, a Scottish police detective, who is present on the scene of most of the significant events of the story. As they and Jackson each attempt to do the right thing, the “one good turn” for another person, the casualties mount up and the circumstances become ever more ridiculous. Instead of “one good turn deserves another,” it’s “one good turn deserves a murder.”

I guess you could say there is a larger mystery that encompasses all the smaller, bewildering coincidences that occur in the course of this tale; but the mystery isn’t really the point. The development of characters is the point, and the action is reliant on the personality quirks of each individual who enters the story to leave footprints, large or small. I would venture to say that Atkinson is evolving a formula, but it’s definitely not one that would be recognizable to mystery readers who are looking for logical plots, clear indicators of right and wrong, and a satisfying conclusion (although there is a final twist in this one that is definitely gratifying).

Atkinson does have a bad habit of introducing her characters and then going off on rambling revelations about their back story while the reader is hung up in the dramatic moment left in freeze-frame until she is done. But the jerky, start-and-stop momentum of this book seemed congruent with the atmosphere of a city overwhelmed by distracted holiday-makers, and we do eventually get to the point (or points).

There was less of Jackson in this one than I would have liked, and also less of Louise the police detective, who is obviously meant to be a love interest at some point (and if she’s not, I’m going to be unhappy with Kate). But the writing is a joy, and I will continue on with the Brodie saga, out of sheer curiosity about what choices he will make next.

The Hideaway

Lauren K. Denton’s book was one of those that popped up as “recommended for you by Amazon” while I was shopping for other things (velcro fasteners and washi tape, so go figure), but it sounded appealing and I love “discovering” debut authors, so I bought it for my Kindle.

It was pleasant, well written, and ever so slightly generic. The story is about two women from the same family in different time periods, experiencing revelations about their lives while ensconced at The Hideaway, a large, rambling old Victorian bed and breakfast in the deep South.

Mags was the grandmother, recently deceased, who ran away

Mags was the grandmother, recently deceased, who ran away

(as a young woman) from her upscale Mobile, Alabama debutante lifestyle to a tiny town by the shore when she realized that her cheating husband was never going to change. Sara is the granddaughter, owner of a smart antique shop in New Orleans, who left her past in that tiny town behind, but now inherits the B&B from her grandmother and is left with the task of rehabbing it and bringing it back to life. The Hideaway is inhabited by an eccentric crew of seniors who arrived when they and Mags were young and ended up staying until they were old.

Each of the women is also given the opportunity of a life-changing relationship and has to decide whether to choose true love or solitude.

The story is told from the two women’s viewpoints, although in the third person, and jumps back and forth between the 1960s and the present. The characterizations are good, and there are some details (such as the wood-working suitor who engraves a key somewhere on every piece of furniture he makes as a symbol of his love) that are engaging. But there is a vagueness about some of the details that makes the story less than credible, and though none of it goes so far as to be ridiculous, the lack of explanation keeps the story from having as much impact as it could have had.

For instance, the original owner of the B&B walks away, leaving it in the hands of the youthful Mags, but there is never a detail about deeding it over. Likewise, with all the people who move in and never move out, it’s nebulous how Mags manages to make a living and keep the house together, since she’s not bringing in regular profits from turning over B&B guests. Likewise, Sara is left the house with the expectation that she will rehab it, yet we don’t learn how she is supposed to meet this expense—did Mags leave plenty of money to do so? because Sara’s small business in New Orleans certainly can’t support that kind of project; but again, we don’t know and are not told where Mags would have found the resources to leave.

I mildly enjoyed the book; it falls into that “new” category of relationship fiction that is my coined term to avoid using the to-me-perjorative “women’s fiction” label. As Liz Kay says in her excellent essay, “What Do We Mean When We Say Women’s Fiction?”: “We get stories about how to be better mothers, or how to understand our own mothers, or how important the bond between sisters is. We get romantic comedies that remind us that we too can be chosen if we just fix whatever it is that’s broken—our workaholic tendencies? Our distrustful independence? Our slutty ways? Something is broken in us, and if we fix it, we’ll be rewarded with the love that tells us, yes, we have value.” Denton’s book definitely falls squarely in the center of this description. But Kay maintains that if we as women desire to read books about mothers and sisters and lovers, they should include those whose flaws never get fixed.

“Fiction, all fiction, should challenge and expand our empathies, not simply reinforce the same assumptions, the same rules.”

Her ultimate conclusion about so-called women’s fiction is, “I don’t want to talk about how to be a woman in the world. I want to talk about the world we’re being women in.” I would have to agree.

One of Denton’s recommenders says, “…the perfect book for an afternoon on the back porch with a glass of sweet tea.” Although this presents an image that’s a little cloying, it’s not all wrong. I wouldn’t go so far as to denigrate this book, but it’s not stepping up in the manner that Kay advocates. I did love all the detail about the house itself, and the descriptions of the furniture carved by William. Sometimes, although reading the story doesn’t do it for you, the small details of the daily life being depicted are nonetheless seductive!

Afterthought: One curious point about The Hideaway is that it was published by the Christian house Thomas Nelson Zondervan; yet there was virtually no overtly religious message anywhere in the book. At one point, one of the inhabitants of the B&B persuades Mags to attend her Baptist church, which Mags describes somewhat derogatorily as “just what she expected,” which is to say singing, praying, and a fire-and-brimstone-wielding minister. You think she is going to have a moment when the minister calls for silent prayer and Mags wonders if she is finally ready to give up the past, but just as she is descending into her first-ever communication with God, the minister breaks into the silent prayer time, and Mags concludes to herself, “Just as well, I wasn’t ready to give it up anyway.” That, and a nod to God in the author’s acknowledgements, was it. One cynically wonders if this tidbit was added simply to qualify for publication?

Call Down the Hawk

The mind of Maggie Stiefvater is a strange, labyrinthine forest of compelling characters, lyrical prose, and tantalizing half-formed truths not quite available to anyone but her.

This much-anticipated book is the first of a new trilogy that nonetheless revisits some familiar characters. Starring in this series are the Lynch brothers—Declan, Ronan, and Matthew—previously seen in Stiefvater’s Raven Boys books, plus a new dreamer, Jordan Hennessy, and her creations, a host of doppelgangers pulled from her sleep-time. All of these actors—familiar and unfamiliar—are fascinating, fallible, and easy to like or at least to follow.

This much-anticipated book is the first of a new trilogy that nonetheless revisits some familiar characters. Starring in this series are the Lynch brothers—Declan, Ronan, and Matthew—previously seen in Stiefvater’s Raven Boys books, plus a new dreamer, Jordan Hennessy, and her creations, a host of doppelgangers pulled from her sleep-time. All of these actors—familiar and unfamiliar—are fascinating, fallible, and easy to like or at least to follow.

Less sympathetic because harder to fathom are the “Zed” (dreamer) hunters who are on a mission to kill due to some nebulous vision that a dreamer will end the world if not stopped. The only one of these we get to know in some measure is the enigmatic but sympathetic Carmen Farooq-Lane; the rest of her “crew” by uneasy association (Lock, Ramsay, etc.) are mere names and occasional paragraphs of words, all hired, paid, and spurred on by an unnamed organization about which we are fated to know nothing, at least in this volume. Equally puzzling are the Visionaries who are in on the kill by association, in that their visions lead the hunters to the dreamers.

But it’s hard to understand where they came from, what was their original purpose, and why they are cooperating in the death of people who are, let’s face it, more sympathetically aligned with them than are these killers.

You will get from this description that there are parts of this book that are clear, linear, and engaging, and other parts that are frustrating, tangential, and confusing.

I was happy to see Ronan in the driver’s seat. I was less happy with the few glimpses we get of his paramour, Adam, away at college, but there are implied promises that Adam will reappear down the road. I loved the revelations about Declan’s persistent efforts to present a false face to the world, because in The Raven Boys and sequels I found his stance unbelievable and knew there was something better underneath the smug, preppy exterior. The new character(s) Jordan Hennessy, with her skills and her plight, are interesting and endearing and make you hope for their salvation. The exterior details surrounding everyone—the art forgeries, the black market, the odd foreshadowy people who turn up here and there, the bizarre real estate—give an extra depth to the story.

This is definitely not a stand-alone work, what with all of its many implications left hanging. Truths are almost but not quite revealed about so many puzzles left over from The Raven Boys books or opened up for speculation in this one—the origins of Niall and Aurora Lynch, the disembodied voice of Bryde hocking Rowan from his dreams, the as-yet-unknown Dreamer X who is responsible for the hypothetical apocalypse…. This book is made of dreams and, like the dreaming mind, it all seems to make perfect sense until you wake up and realize you have a lot of questions! Can you please write a little faster, Saint Mags?

This is definitely not a stand-alone work, what with all of its many implications left hanging. Truths are almost but not quite revealed about so many puzzles left over from The Raven Boys books or opened up for speculation in this one—the origins of Niall and Aurora Lynch, the disembodied voice of Bryde hocking Rowan from his dreams, the as-yet-unknown Dreamer X who is responsible for the hypothetical apocalypse…. This book is made of dreams and, like the dreaming mind, it all seems to make perfect sense until you wake up and realize you have a lot of questions! Can you please write a little faster, Saint Mags?

Crossover novels

Two of my favorite YA books of recent years were written by the same person. She’s not a well-known author, and not that many people have read her books compared to the overwhelming numbers who buy every book written by realistic fiction writers Sarah Dessen, John Green, or Rainbow Rowell. But if you haven’t read at least two of her books, you’re really missing out.

I just did a re-read of her first,

I just did a re-read of her first,

I’ll Be There. Previous to writing this realistic YA novel, Holly Goldberg Sloan was a screenwriter for family feature films, and some of that particular skill comes across in her first novel. It’s told in third person omniscient, so there isn’t nearly as much dialogue as you might expect, but you do find out a lot about the characters from the inside out, as you follow their thoughts about those with whom they are interacting. And these insights are a big part of the magic of this book.

Emily Bell is just a regular girl. Her mother is a nurse; her father is the choir director at their church; and she has an endearing little brother and a dog. Up until her 16th year, Emily’s life has followed a fairly conventional path. But as a result of taking one risk, she meets a boy unlike anyone she has ever known before, and this boy is going to change Emily’s destiny in a multitude of ways.

I know what you’re thinking: A meet-cute, followed by insta-love and some kind of semi-fake drama that throws them together or tears them apart or whatever. But this book, while written simply and clearly with largely knowable and understandable characters, is anything but typical.

Sam Border and his little brother, Riddle, have lived a life that is the polar opposite of Emily’s prosaic suburban existence. Their father, Clarence, a narcissistic grifter, stole them from their mother when Sam was in grade school and Riddle was little more than a toddler, and they haven’t had a home since. They travel wherever the luck takes Clarence, living in condemned houses and broken-down trailers, sometimes sleeping in Clarence’s truck. Sam never made it past second grade, and Riddle has never attended school.

When Emily and Sam meet and get together, each one is a conundrum to the other. Sam may see Emily more clearly than Emily sees Sam, because he knows the circumstances in which she was raised, while Emily has no clue about a life that doesn’t include a clock or a cell phone, in which people forage for leftovers from the trash at the fast food place and never know when they will be moving on. All Emily really knows about Sam is that he is different from anyone she has ever met, and she wants to know more. Their worlds are bridged by their attraction for one another.

Emily’s parents, concerned about their daughter’s fascination with this stranger, encourage her to bring Sam home to dinner, and when they begin to figure out what Sam’s life must be like, and then meet Riddle for the first time, their concern shifts to a desire to help. But the paranoid Clarence, who has trained his boys in how to remain invisibly under the radar, interprets this attention as a threat, and once again the boys are launched into the unknown, dragged at Clarence’s heels. This time, however, someone knows, someone cares, and someone is looking for them.

The book is filled with whimsy, pathos, humor, tragedy, and love. I have read it three times, and can imagine reading it again a few more. The book reminded me a bit of Trish Doller’s book Where the Stars Still Shine, because of the similar circumstances of a parent who lives his or her life with almost total disregard for the well-being of the children.

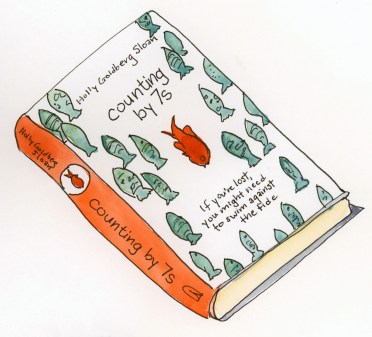

Sloan’s other notable book is called Counting by 7s, and was Amazon’s best novel of the year for middle grade when it came out in 2013. Although it, too, highlights a child who is different from everyone around her (the one fish swimming against the current), it could scarcely be more different a story than the romance between Emily and Sam.

Willow Chance is a 12-year-old genius, a quirky obsessive-compulsive whose life was saved when her parents adopted her as a small child. Although she doesn’t fit in well with her peers, her multitude of interests (medicine, gardening, languages) keep her happy, if solitary. (Think of Sheldon Cooper as a small mixed-race girl.) Tragedy strikes when both her parents are killed in an automobile accident and Willow has to confront the possibility of foster care while doing without the love of the only two people who ever made an effort to understand her. What she does to reconstruct her life and find a family will keep you riveted to the end.

The only similarity of this book to the first one is Sloan’s multi-character-driven storytelling, which makes Willow’s story particularly vivid. The writing is spare yet incredibly dense in detail, if that’s possible. Although this book received a lot of attention from a multitude of literary awards geared towards writing for young people, I have always argued with my librarian colleagues that while it is about a middle-school-age child, the story is more sophisticated than can be appreciated by children of that age. One Goodreads reviewer conceived of Willow as “an American Matilda,” that beloved heroine created by Roald Dahl, which I thought was particularly insightful; and another character of whom I am reminded is that of Flavia de Luce, the amateur chemist and sleuth from Alan Bradley’s mystery series that began with The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie. There, as here, while the protagonist is a young girl, the story is for adults.

Don’t miss out on these two stories. Whether you are a teen or a grown-up, they are well worth your reading time.

How Fear Departed the Long Gallery:

How Fear Departed the Long Gallery:

“The Gift of the Magi,”

“The Gift of the Magi,”