My Year in Books 2025

I managed to read quite a few more books this year than last (95 to 2024’s 66), but I don’t know that I realized much advantage from doing so, beyond just clocking the reading time. My stats, according to Goodreads, were:

95 books

28,425 pages read

Average book length: 346 pages (longest book 908 pages!)

Although I discovered some enjoyable reads, there wasn’t one single book that truly bowled me over or made me immediately check out another book by that author or settle in to read a lengthy series. And most of the books I did like were the lightweight ones that I ended up reading as a sort of relief between the tougher titles. Here’s a list:

The Lost Ticket, by Freya Sampson

The Busybody Book Club, also by Freya Sampson

Vera Wong’s Guide to Snooping (On a Dead Man),

by Jesse Q. Sutanto

Finlay Donovan Digs Her Own Grave, by Elle Cosimano

My favorite science fiction book was The Road to Roswell, by Connie Willis.

My new discovery in YA fantasy, with an intriguing Egyptian-like setting, was His Face is the Sun, by Michelle Jabes Corpora. I look forward to the sequel(s).

I read a few books that were award-winners, or by well-known literary authors, or touted by other readers as amazing reads, but found most of them problematic in some way, and therefore didn’t feel wholeheartedly pleased to have read them. They were:

James, by Percival Everett

The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo, by Taylor Jenkins Reid

Horse, by Geraldine Brooks

The Mare, by Mary Gaitskill

Horse Heaven, by Jane Smiley

Three Days in June, by Anne Tyler

Gentlemen and Players, by Joanne Harris

These have all been reviewed on this blog, so do a search for the title or the author if you want the specifics. None of them received a thumbs-down, but none of them lit up my imagination either.

The most disappointing part of the reading year was the letdown I felt each time I finished the next book in a bestselling series I had previously enjoyed. I read two books by Michael Connelly—The Waiting, and Nightshade—and had a “meh” reaction to both. The Grey Wolf, by Louise Penny, didn’t deliver the characteristic Gamache love, and was filled with tangents and extraneous story lines. Perhaps the least successful (for me, at least) was The Hallmarked Man, by “Robert Gabraith,” aka J. K. Rowling, which was so endlessly convoluted that I felt the need to reread it—but so long, wordy, and unsatisfying that I didn’t! I’m really hoping these authors rally in the new year, but it’s more of a “fingers crossed” than an actual expectation.

Honestly, my best and most sustained reading took place when I got fed up enough to revisit beloved books from decades past by such authors as Rumer Godden, Georgette Heyer, and Charlaine Harris.

Today I am starting on 2026, two days ahead of schedule! Onward, readers!

Starts with “D”

I haven’t been on here for a while because I started reading a trilogy and decided that, since all three books were already published and I could read straight through it, I would wait until I was finished and review the whole thing.

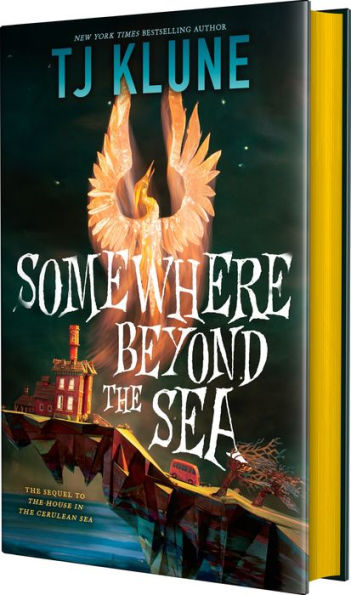

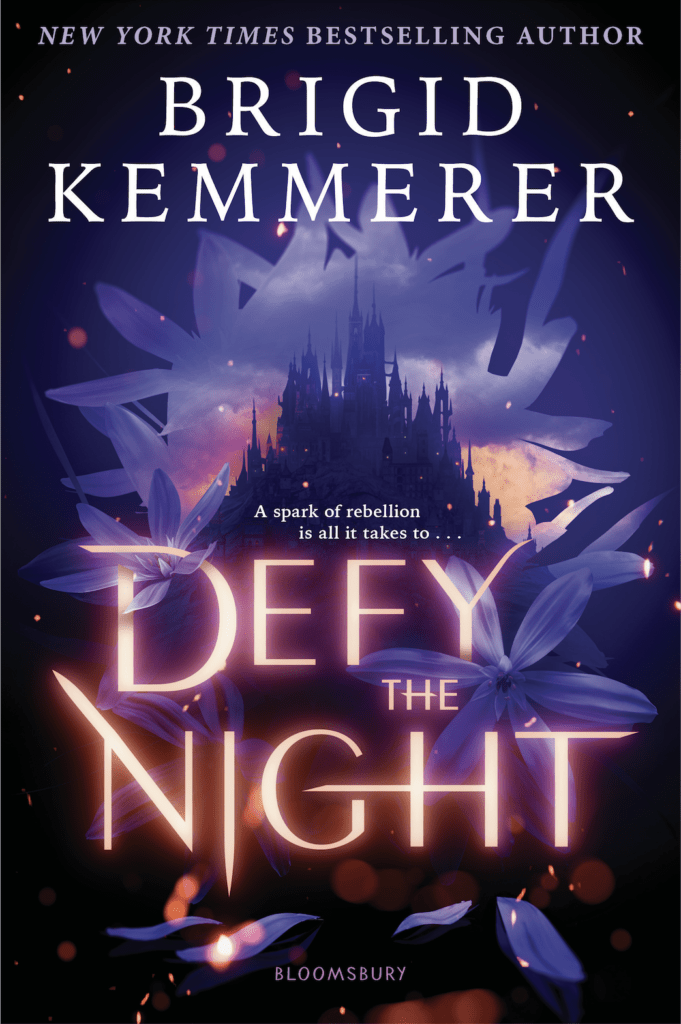

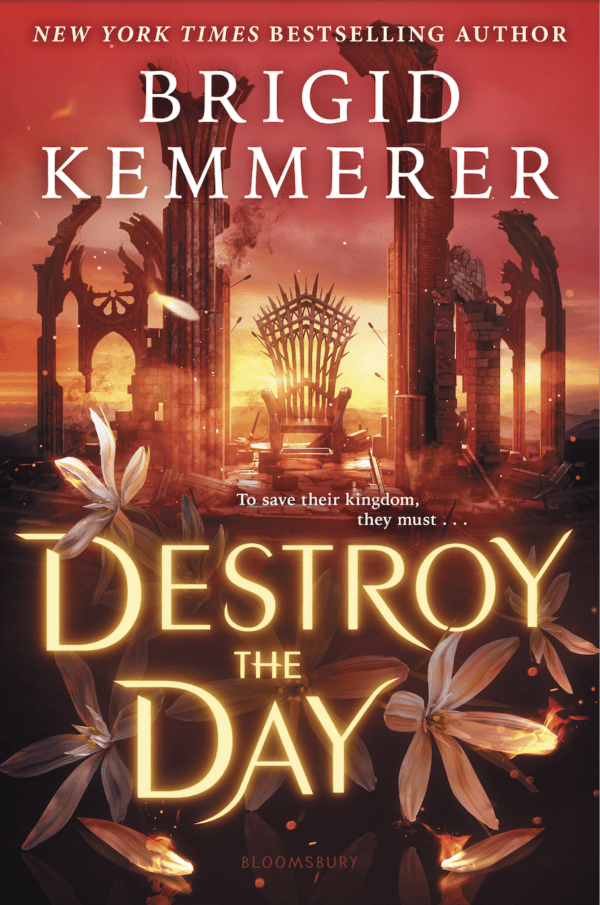

The trilogy is by author Brigid Kemmerer. The books are Defy the Night, Defend the Dawn, and Destroy the Day. I can’t say that I totally get the significance of each book title in context of the overall story, but you have to call them something, right? And alliteration always sticks in the brain…

I first discovered Kemmerer when I noticed her “Elementals” series in the YA stacks at the library, about four brothers with paranormal powers. I wasn’t drawn to those at all, and never read them, but when I read her stand-alone non-fantasy young adult novel Call it What You Want, I was bowled over and immediately followed up with the duology Letters to the Lost and More Than We Can Tell, and then found her other stand-alones.

When she started writing fantasy again, I felt confident to buy these books for my teen readers, but I had a little misgiving, because her first outing in the Cursebreaker series was a retelling of the Beauty and the Beast story. Since I would always prefer an original story to a retold tale, and since B&B is also one of my least favorite fairy tales, I almost regretted it; but I liked her writing enough to give it a chance, and ended up appreciating what she did to make it less sexist and cringeworthy! I never got around to reading any of the sequels, because I concluded that her real strength lies in writing about real teenagers in the throes of their confusing, sometimes difficult lives. But when I noticed this new trilogy and realized she had just finished it, I decided to check it out.

I did enjoy it; but I don’t think it changed my mind about where her true gifts lie, and I’m kind of sorry about that, because it seems she has fully committed to fantasy at this point in her career. Don’t get me wrong: The books are good, with flowing prose, great characters, decent world-building, and an original fantasy story (not a retelling this time). I just like her contemporary teen novels much better.

These are likewise meant for older teens; but that was one of the things I had a little difficulty accepting. The main characters, including the king and his brother the king’s justice (think enforcer) are all supposedly under 20 years old and, given that they have been ruling the kingdom of Kandala with an iron hand since they were 18 and 15, believability was strained. When in the third book the younger brother (Corrick) turns 19, I immediately thought yeah, no way. The story would have been much more realistic had the characters started out in their early 20s, but I guess that would disqualify the books for YA publication?

This trilogy is filled with political intrigue and drama. The basic plot is this: Harristan and Corrick’s parents are assassinated by one of the kingdom’s consuls, and Harristan becomes king of Kandala at the tender age of 17. Shortly after the brothers find themselves thrust into power, a devastating illness begins to spread throughout the kingdom. There is a remedy, a flower that grows in just two of the districts of Karala, each ruled by a consul, but the availability of the elixir made from Moonflowers is limited and the consuls who control its source are holding the kingdom hostage by doling it out selectively and at a high price. There isn’t enough to keep the common people from sickening and dying, and rebellion seems imminent.

Prince Corrick, frustrated by his role as King Harristan’s enforcer of the strict laws against smugglers and illegal traders of the blossoms, sneaks out at night to meet up with commoner Tessa, a young apothecary whose parents died trying to help their neighbors. He masquerades as Weston Lark, a young revolutionary, and the two bring doses of the elixir Tessa brews from the petals they are supposedly stealing from the palace to the folk living in the Wilds, but it’s never enough. Events take a turn that cause Tessa to try to sneak into the palace to confront the king, but her intentions in taking this step are changed when she discovers that nothing is as she expected when it comes to Harristan and his brother.

There are several big twists and surprises starting in the first book and continuing in the other two. In the second, some of the characters respond to an offer of help (and trade) from the neighboring kingdom of Ostriary and agree to go there to research the possibilities, leaving King Harristan to try to fix his dangerously divided kingdom, and the third book wraps all of it up and brings everyone back together. I don’t want to say more than that about any of it, because if you plan to read it you will need to experience it as you go, but it’s sometimes great, mostly good, and also has its occasional dull moments or weird segues like most fantasies do. There are a few things that frustrated me because they either suffered from inadequate explication or remained completely a mystery; but over all, a worthy effort. Kemmerer’s lively and interesting characters are, as always, her strong suit.

The last?

I just finished what has been billed as the “last installment” of the Gunnie Rose story by Charlaine Harris—The Last Wizards’ Ball, number six in the series. And although I thought that it was appropriately told, with plenty of drama and intrigue and some fascinating new characters, I admit I am feeling a little puzzled. There was no cliffhanger as there was at the end of previous installments, but everything was left more than a little unsettled and open-ended, and I could see this series going on for several more books, based on the impression I received from this one. I can’t decide whether Harris likes an open-ended story, or is hedging her bets just in case.

Of course, one could posit a spin-off or two that, for instance, followed Felicia to New York City and then to Europe, or trailed Lizbeth to a possible new home in a place both greener and less fraught than Texoma, or followed the fortunes of Eli as he resumes his services to the Russian Tsar of California…

Just to inform those who are unaware of this series…

The setting is the former United States, but one event—the assassination of Franklin Delano Roosevelt—has significantly altered the history of the country. Without Roosevelt’s guiding hand during the Great Depression, the crippled country fractures, and various states were either absorbed into surrounding countries, taken over by former rulers, or banded together to form small nations. The original 13 Colonies pledged fealty to the British Empire; a few of the “top” border states became part of Canada; the south-eastern states are now “Dixie” while Texas and Oklahoma formed “Texoma”; the “flyover” states remained “New” American territory; the rest of the southwest was annexed by Mexico; and the biggest surprise was the Pacific Northwest, which was taken over—by a combination of invitation, treaty, advantageous marriages, and magic—by Tsar Nicholas and the remains of the Holy Russian Empire, which is now its new name.

The main protagonist, Lizbeth Rose, lives in Texoma and makes her living by hiring herself out as a “gunnie”—a combination of escort, guard, and gunslinger paid to protect people and/or cargos being transported by land or rail from one territory to another. It’s an unusual profession for a young woman, but Lizbeth is a crack shot used to relying on no one but herself, and takes all the risks to keep her clients alive and her cargos safe. Here is my full review of the first two installments, which also further explains the magic part of the tale.

In this the sixth book, Lizbeth Rose’s half-sister Felicia, a powerful wizard, is 16 and attending her first Wizards’ Ball, described by Lizbeth as similar in nature to the “Season” in a Georgette Heyer novel, otherwise known as the Marriage Mart. The most prominent grigoris, wizards, and magic-makers from around the globe send or bring the eligible members of their families (unattached youth under 30) to a week-long series of garden parties, tea parties, balls, theatricals, and what-not so that they can all meet one another and make suitable marriage matches. The aims are power (both magical and political), wealth, and the acquisition of a bloodline that will match well with, freshen, or diversify a perhaps played-out heritage.

Felicia is much in demand but also at great risk, since some would do anything to “acquire” her and her power for themselves, while others are bent on keeping that power away from those people, regardless of Felicia’s personal wishes. But Felicia is no pushover when it comes to defending her own rights, and she has her gunslinger sister and her grigori brother-in-law, Eli, along for protection and observation.

The time period in this book is during the build-up to what was, in another timeline, World War II—the ascendence of Hitler—and all negotiations are colored by political loyalties and intentions as it becomes apparent that war is in everyone’s future. This is part of the reason why I find it confusing that this is the last book, because in a world where there was no strong, unified American government with its military that jumped in at the end to turn the tide of the war, the possibilities are endless, and Harris has set it up with the added detail of magical abilities being in play on both sides.

While the book was entertaining, full of plots, drama, and detail, I was left feeling that if this was the end of the story, we have been dumped just as things were about to get truly intense. I’m hoping that Harris has a segue up her sleeve, as she did when she wrote the Midnight, Texas stories based on a character from her Harper Connelly series. If not…I have quite enjoyed them anyway, some more than others.

Diana Wynne Jones

I have spent a lot of quality reading time with the novels of Diana Wynne Jones. Although she writes mostly for middle-schoolers, there are also a handful of books that, while ostensibly for the younger set, have content possibly more suited to the adult fantasy reader. My favorite of hers is Howl’s Moving Castle, which is definitely one of those that appeals to a wide range of ages; I also enjoyed its two sequels, which are not up to the first one but are nonetheless good. And I will argue with devotees of Miyazaki that if you have only seen the animated movie made about Howl, you have not experienced Wynne Jones’s version; while the film is a truly delightful visual expression, it doesn’t begin to offer the nuance of the book itself. The other series of hers I have read and enjoyed is the Chrestomanci Chronicles, which are near-perfect fantasies for middle-schoolers. I have not read Dark Lord of Derkholm, but will no doubt get to it one of these days, as I will the Dalemark Quartet.

Her stories often combine magic with science fiction, bringing in fairy tales, heroic legends, parallel universes, and a sharp sense of humor that sometimes verges on satire or parody. There are levels to her books that are the key to making them enjoyable to a wide age range; young children can read them for surface enjoyment while older teens and adults get the jokes.

This past week I discovered that she also has some free-standing novels, and picked up Fire and Hemlock, which had an intriguing story line for which, in hindsight, I should have been better prepared.

The book owes its structure and character line-up to the ballad of Tam Lin, which dates from 1500s Scotland, and also to the story of Thomas the Rhymer, an actual Scots laird who lived from 1220 to 1298 whose story is confusingly similar to that of Tam Lin (both of them were kidnapped by the Queen of Elfland, although their destinies diverge after that initial act). I was embarrassingly unfamiliar with either of those legends going into reading this novel, and should have stopped the minute things got complicated and consulted Wikipedia for the synopses I finally ended up reading after I was done! Take heed of my experience and do that before you read this book if you want it to make sense. There are also echoes of both Hero and Leander and Cupid and Psyche, with echoes of T. S. Eliot. Diana Wynne Jones has written an explanation of her thoughts about the heroic that was included with my Kindle copy of the book, though it doesn’t appear except in later printed editions.

In the book, Polly Whittaker, 19, suddenly realizes that she has a set of double memories that began at the age of 10, which some entity is trying to make her forget. In the mundane set, she has been living an ordinary life: school, books, athletics, friends, irresponsible and uncaring parents, a loving but acerbic grandmother, and a boyfriend she’s not sure she wants. In the fantastical one, many of her actions are dictated by her sporadic but compelling friendship with a man she meets at a funeral, with whom she has an odd affinity. They experience some strange, inexplicable adventures together—are they truly magical?—but their friendship is threatened by menacing characters and events from which Tom Lynn attempts to shield Polly. She finally figures out what’s happening when it’s almost too late, and takes drastic action to secure both the memories and the relationship.

The book is such an odd mix of juvenile and adult that it was hard to read at some points, because it fluctuates between the mind of a young, naive girl and the definitely adult legend of a man in thrall to a wicked force that wishes to control his life. The narrative is carried by Polly, so we see everything through her clever and imaginative but innocent eyes, and if you are reading the book without knowledge of the backstory, it can be both frustrating and confusing, as well as long. I ended up liking it pretty well, and it’s probably Wynn Jones’s most ambitious plot in terms of the multiplicity of strands she introduces, but I was definitely happier with the straightforward, more mature, and somewhat humorous world of Howl’s Moving Castle.

Egypt by another name

I picked up a Kindle deal for a new YA fantasy a few weeks back, and finally got around to reading it. The book is His Face is the Sun (Throne of Khetara #1), by Michelle Jabès Corpora, and it’s being billed as something that the readers of several other teen fantasy writers (Bardugo, Mafi, Tahir) would enjoy. And although I believe that is true, I’m not sure they should have focused it so relentlessly at the Young Adult market. In fact, I often feel that way when it comes to fantasy and science fiction.

In other genres (realistic stories, romance, coming of age), the audience can be clearly demarcated as teens, ages 13-18 or whatever—many adults aren’t interested in teen angst-ridden 15-yo first love stories. But with fantasy, if the world-building is thorough and convincing and the protagonists are engaging, I often feel these books are done a disservice not to be marketed widely. This one, for instance, ended up pretty quickly in the bargain Kindle bin (I think I paid $1.99), and it shouldn’t have, because it’s a really beguiling read. So adult fantasy lovers, pay attention and check it out, because if you enjoy it, there are two more books to come. (Also, this series is directed at more mature teens, due to some frank content, just fyi.)

The kingdom of Khetara is a faintly disguised Egypt, with some of the same gods under the same names and also under different ones, and similar dynasties of rulers and conquered peoples. It could almost be historical fantasy, but the author chose to create her own stage within the auspices of Egyptian history. There are priests and oracles, there are competitors vying for the pharoah’s throne, there are rebellious mistreated commoners, all set against a background of desert, river, village, palace, and temple, brought to life in beautifully detailed descriptions (that don’t slow the story at all). There is a mythology-based magic system that winds through the entire story in an organic manner and, although there is a little romance, this is primarily an epic fantasy focused on history, politics, magic, and destiny.

The main characters are four people who couldn’t be more different: Princess Sita, one of the triplets to whom the current Pharoah is father; Nefermaat, a bewildered young village girl who, after a spontaneous vision brought on by the annual parade for the goddess Bastet, has been whisked from her home to the capitol to train as a priestess; Raetawy, leader of a rebel group of farmers oppressed by the pharoah’s punitive taxes; and Karim, a young grave robber who unearths more than he bargained for and sets in motion some of the events envisioned by Neff and anticipated by Sita’s brother Mery, who is determined to rule Khetara sooner rather than later.

Although four protagonists is a lot, Corpora does a wonderful job of developing each of them with clear personalities and motives, and separates their subplots (politics, magic, rebellion, and fortune-seeking) while intersecting them at the appropriate moments to keep us intrigued. (Oh, and there’s a delightful fifth narrator—only encountered a few times—who further draws things together.)

I was completely involved in this story from beginning to end and, when I encountered that cliffhanger and realized that this book had just been published in May and I would have to wait at least a year for the next one, was sorry that I had read it so quickly. I will do a reread when the sequel comes out, to catch all the delightful detail that I may have skimmed over while trying to absorb the book as a whole. If you ever thrilled to the stories of adventures down the Nile, hotly contested dynasties and mysterious portents, you will want to read His Face is the Sun.

Discworld

As I mentioned in my Cat Day post, I continued on with Terry Pratchett’s witch tales by reading Wyrd Sisters, and then when I finished that I ducked out of the witch-specific books and instead assayed Mort, the first of the series with Death as its narrator.

For me, although I love the witches themselves, the most delightful part of Wyrd Sisters was the traveling actors with whom a certain very important player in the fate of the kingdom of Lancre shared a river boat, a wagon, and a stage. His talents there also serve him well when it comes to inhabiting his true destiny on Discworld, but the descriptions of the individual performances, some untrammeled but others under the influence of the witches’ meddling with time, are hilarious homages to Shakespeare.

The brief cameo of Death in this book led me to read his shared autobiography with young Mort, whom Death solicits as an apprentice of sorts, so Death (or DEATH, as he is known colloquially) can take a vacation to experience what it’s like to be human. He assiduously takes part in all the pursuits that humans seem to enjoy most (fishing, drinking, and so on) and is somewhat underwhelmed. But while he’s off getting his human on, Mort is messing with the fabric of time, destiny, and fate by refusing to off some of the people whose hourglasses have run out. Mort is horrified by the prospect that he might have to inhabit this role forever if DEATH continues AWOL, and takes steps, assisted by DEATH’s adopted daughter Ysabell.

I think I can sum up Pratchett’s sense of humor when I tell you that DEATH’s pale stallion that he rides across the wind and stars to usher souls into the next world is named Binky.

While I generally prefer books with more gravitas, I can see that an occasional foray into the bounds of Discworld will be a welcome vacay read for some time to come.

Pratchett

I don’t know how, in my decade-long exclusive pursuit of all things science fiction and fantasy, I managed to miss out on Terry Pratchett. I discovered some of the contemporaries to whom he is frequently compared (Douglas Adams, Piers Anthony), but it took another 30-some years and a degree in library information studies before I was introduced to him via the Tiffany Aching portion of the Discworld books. As a teen librarian, Pratchett came to my attention through the offices of The Wee Free Men; I was really taken aback when my high school book club didn’t love it as much as I did, but I didn’t let that deter me. I read every Tiffany Aching book (five total) that was out or came out thereafter, and loved them all, but for some reason I still didn’t go back (as I normally would) and explore all the other Discworld books.

Perhaps it was because of the sheer volume of the series—41 books is a lot to tackle, and I no longer read with the obsessive one-track mind that I did in my 20s, when I let nothing stop me from completing a series start to finish. But I was at extreme loose ends this week after finishing In This House of Brede; I initially moved on to another Rumer Godden but discovered that i was satiated for the moment and was craving something different. None of my holds are even close to arriving, so I went searching for something else by running my eye down my “Want to Read” list in Goodreads.

This is when I most miss being mobile; my finding process used to entail going to the library and looking at the new books and the just-returned shelves, and then wandering down aisles of my favorite genres—mystery, fantasy, science fiction—to see if old authors had new (or older) works I hadn’t yet discovered. It’s a lot easier to find an unknown treasure that way than it is to scroll through lists on the internet, as I do now that I am essentially housebound. There are the visual, physical, tactile elements of cover art, author quotes, flap summaries, the feel of the paper, the choice of font, the smell of the book, all of which yield up something that helps me make a decision. By comparison, it’s a sterile (and also endless) process to scroll through (sometimes erroneous) Goodreads descriptions, look at the ratings posted by other people, and speculate about whether I can choose something just based on these paltry factors.

This is partially what took me to Terry Pratchett—there was at least some experience, some familiarity with his story-telling and writing style, his characters, his world-building. I did pay heed to several people who said the first two books in the Discworld series, while introductory, were not his best writing, and that to start with #3 was a good beginning, particularly because it is also the debut of Granny Weatherwax, with whom I was already familiar from the Tiffany Aching books. So I acquired a copy of Equal Rites from Kindle Unlimited, and began my exploration of Discworld.

One thing you forget, if you go long periods between Pratchett tales, is his sense of humor and how he exploits old sayings, puns, wordplay. And even though Pratchett’s powers developed exponentially as he wrote each subsequent book, the humor is here from the beginning. The first one I wanted to write down the instant I read it was when Granny Weatherwax decides to find accommodations in a new town; she comments that she has specifically elected to live in an apartment next door to a talented and successful purveyor of stolen articles, because she has heard that good fences make good neighbors. Ba dum bum.

Equal Rites is the story of young Eskarina, who is mistakenly selected to be an heir to wizardry. A wizard comes to Granny Weatherwax’s village of Bad Ass seeking the child to whom he is to hand over his staff before his imminent demise; the smith of the town is an eighth son whose wife is about to give birth to his eighth son, which is highly propitious. So when the wizard realizes he has six minutes to live and Granny, having just delivered the baby, carries it into the room, the wizard places the child’s tiny fingers on his staff to claim it, and then expires before he can discover that the eighth son is actually a girl.

On Discworld, gender equality is a dream—at least for women. Only men are wizards, just as only women are witches. Men have, of course, tried being witches (because they don’t take no for an answer), but it has never worked out well; but those same men have banded together and insisted that “the lore” absolutely forbids women to be wizards, and no woman has ever been admitted to Unseen University as a candidate. Granny W, however, is determined that Esk should at least have the chance (as is Esk herself), so the two set out on a journey to the city of Ankh-Morpork, for Esk to try her luck. This is the basis for the chaotic hijinks that ensue for the remainder of the book.

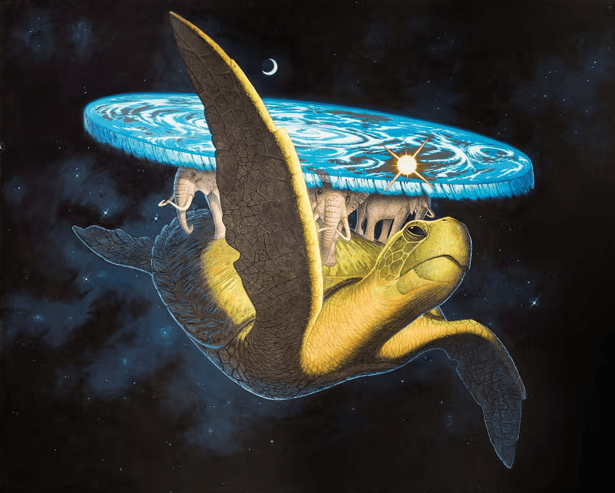

I really enjoyed both the introduction to Discworld and the reacquaintance with Granny W. (and with Pratchett). I think I will continue on for a while; they say you can just read the “witch” books (of which there are six) on their own, but I might also branch out into other characters’ tales set on this flat world carried on the back of a giant turtle and four elephants.

The Empyrean “trilogy”

This series by Rebecca Yarros has been hyped a lot. I usually shy away from that, because I have discovered it’s more often than not the kiss of death to my enjoyment. But…dragons. I love dragons. I read all of Anne McCaffrey’s Pern books at least three times. I adore the dragons of Patricia Wrede, Bruce Coville, Diana Wynne Jones, and Angie Sage, and also those in Tolkien’s The Hobbit and Farmer Giles of Ham. I put up with Jane Yolen for the sake of dragons. Dragons gave added value in Ursula LeGuin’s Earthsea books and in the various trilogies by Robin Hobb. One of my favorite series is The Last Dragonslayer and sequels, by Jasper Fforde. I was intrigued by Rachel Hartman’s dragon/human shapeshifters in Seraphina and Shadow Scale. Robin McKinley’s Damar books use dragons as more of an excuse for a story than as a major plot element, but I still loved them. So. I was perhaps predestined to read these.

I will say that I was not initially disappointed by the dragons themselves. They are pretty cool, and the two we get to know more intimately through their association with main character Violet Sorrengail (Tairn and Andarna) have real personality. But there was much less thought put into all the rest of the dragons who appear in the books and, aside from their names being linked as a bonded pair with various characters, they were sadly both interchangeable and underutilized.

As for everything else, well, let’s break it down:

The writing was somewhat pedestrian—way too much exposition, language that was overly ornate but never coming to the point, and modern anachronisms (“for the win” and “shit’s about to get real” are the biggies that come to mind) that took me right out of the fantasy illusion. Sentence structure was awkward. (One reviewer actually counted and said “Yarros used 493 ellipses and 1,089 em-dashes in the 634 pages of Iron Flame.”) Both the meandering plots and the effusive, exclamatory style made me wonder how much power the editor was given over the content of these books (and why it likewise went underutilized).

The character building was good in the first half of the first book, and then disintegrated with each subsequent encounter. The protagonists, Violet and Xaden, had great potential, but knowledge of them stays on a shallow level because the author keeps describing them over and over without adding anything new, and the encounters between them are equally as repetitive. Both the heroism and the villainy become boring, because there’s little depth or explanation. And we might as well go on here to talk about the “romance” between the main characters, because this was an element that made them work even less for me. The first (explicit) physical encounter between them felt hot and daring, but by the time I got through the third book I was cringing and skipping the sex scenes because they were unoriginal replays both physically and verbally.

The secondary characters (Violet’s squad and siblings, the rebels closest to Xaden) had individual quirks that made them lovable or frustrating or inspiring or whatever, but I was disappointed that there was so little growth beyond the naming of that one element that characterized each of them. Much like the dragons, their characters and camaraderie could have been so much more of a feature, had the author cared more, but they were essentially one-dimensional.

The world-building was sloppy. It seemed like the only time it happened was when it was bolstering some plot point, so it became wearisome, for instance, to find out brand-new information well into the second or even third book simply because it was necessary to further the story. The fact that magic dwells only on the main continent, protected by wards, but there are whole archipelagos of islands without it, or that dragons are companions to the people in the warded lands but hated, feared, and targeted by the others would have been enlightening to know halfway through book one, not two-thirds of the way through book two (or later). And as for what magical abilities everybody has, it definitely felt like Yarros was making that up as she went along and needed a Hail Mary to get her out of the situation into which she had written herself. Everything we learned seemed less like a planned surprise and more like a decision in the moment as the author thought of some way to turn the story—oh, did I forget to mention this? Well, let me explain it here for you and then we can move on.

I will also say that since I am not a big fan of romance, maybe “romantasy” wasn’t as appealing to me as it might be to some; but I don’t think that’s really the problem. The problem is the endless, repetitive nature of the supposedly romantic encounters, which is a euphemism for the fact that every time the two protagonists saw each other, it was immediately sexual. Some non-fraught conversation would have been nice. Some peeks into childhood, some sharing of philosophy, a picnic, a book recommendation? Something.

Fourth Wing was good, despite some of these deficits, because we were discovering brand-new information—the challenges of getting into and surviving battle school, the intricacies of bonding with dragons, learning how to navigate the politics of both school and kingdom. It was interesting to learn that Violet had planned and thought she was destined to be a Scholar but was forced, despite her physical frailties (readers said the description of these sounded like she had Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome) and small stature, to choose to be a dragon-riding warrior because her mother was a big-deal commander and wanted all her children to choose that path. The details about Xaden and the other tattoo-marked riders being the children of rebels, basically conscripted into the dragon army to atone for the sins of their (deceased, executed) parents were intriguing. And the physical and mental obstacles Yarros sets up to test the potential riders to prove they could do the job were exciting.

But after the first shocks of a new environment, a new protocol, a forbidden love, the rest seems disappointingly like nothing but reiteration, filler, and false obstacles created to provide constant peaks and valleys in the relationships and the plot without ever taking us much of anywhere new. So (for instance) every time Xaden appears on the page, Violet has to lustfully re-react to his physique, his tattoos, his smoldering expression, his shadow-wielding. Every action or battle scene exists so that brave, impulsive but fragile Violet can be in peril or injured and Xaden can magically turn up to save her, scold her, and have his way with her (after the healers put her back together). And both the action and the storyline depend way too heavily on the life stories of just these two characters. It makes a dull read out of what could have had more significance and nuance.

My biggest beef, however, is that I was ignorant of what was apparently some fairly recent news. This was billed as a trilogy and I was, frankly, delighted to hear that. I wanted to read a series that had a beginning, a middle, and an end within a limited framework. So many fantasies just keep going until they exhaust either their author or their readers, but I thought I had discovered a tale that would be neatly told in three admittedly long but finite books. Nope. I kept reading book #3, at first thinking I should surely be farther along than 37 percent because what was left to say? and then thinking oh, there has to be at least 20 percent more to go because this doesn’t feel anywhere close to wrapping up, and then turning a page to discover, uh-oh, it’s over; WHAT?! I reread the ending of Onyx Storm three times and could make no sense out of it, only to discover (in a footnote on Goodreads on Yarros’s author page) that the rather cryptic close of that book was intentional because…dum dum DUM…there are two more books slated to be published. And after struggling through all the sturm und drang of book three without getting resolution of the central issue in a whopping 527 pages, I was, frankly, pissed off. I think I am done with Rebecca Yarros, despite the dragons. And that’s a big, big deal. Phooey.