Illustration

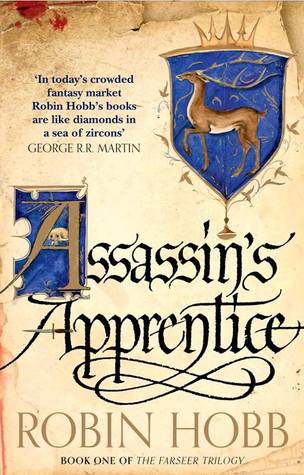

In the category of “Better late than never…”

I had a lesson this week in my year-long portrait-painting class that took as its inspiration Picasso’s harlequins. It was a complicated, lengthy, and convoluted lesson and I almost didn’t do it…and then I got an idea. I decided, instead of painting the boy and girl harlequins like the teacher did, that I would illustrate Robin Hobb’s fabulous Farseer books by making a painting of one of the main characters, the Fool, an albino court jester who (in the early books) sits at the feet of King Shrewd, dressed in black and white motley and playing with a rat-head marotte. So I did, and here it is!

The teacher who taught this lesson is a big proponent of collage, and I found some fun and symbolic stuff for this one. In addition to using tissue paper to good purpose for the ermine of the King’s cloak, I found a dragon, which figures significantly in later books; a Queen of Hearts card, which I interpreted as Queen Kettricken, my favorite female character (well, she was until Bee arrived); and a tiny jester, who is gesturing up towards my Fool from the corner.

Perhaps this will intrigue more readers to look into Robin Hobb’s three trilogies about the Farseers!

Robin Hobb wrote the Farseer Trilogy, the Tawny Man trilogy, and the Fitz and the Fool trilogy. There are also other books set in the same universe, about the Liveships and their Traders, the Rain Wilds, and the Elderlings.

Trilogy the third

I have spent the past couple of weeks immersed again in the land of the Six Duchies, the cities of the Elderlings, the oceans sailed by the liveships, and the mysterious white island of the Servants, origin of the enigmatic character known variously as the Fool, Lord Golden, and Lady Amber. Yes, I am referring to the third and last trilogy by Robin Hobb that details the story of FitzChivalry Farseer and all his many friends, enemies, family members, and connections. The end of the tale was a fascinating, unexpected, breathless pleasure to read—at the same time as I dreaded its conclusion.

After having gone missing for many years without a word to “Tom Badgerlock,” the Fool makes an abrupt and unexpected re-entry into FitzChivalry’s life that spells disaster for all. Fitz’s little daughter, Bee, is kidnapped from her home in her father’s absence, and borne away to the white island of the Servants, who believe she is the “Unexpected Son” of their prophecies and wish to exploit her talents and control her dreams. Given the almost insurmountable challenge of retrieving her (not to mention the two men’s intention to slaughter every single Servant and raze their city to the ground), Fitz and the Fool seek out all the allies they can muster, including visiting the descendents of the fabled Elderlings, engaging with the Traders who sail the sentient vessels known as liveships, and even entreating the aid of dragons.

I didn’t think I could love anything more than the last trilogy, but with the intriguing introductions of new characters and the rediscovery of old ones in this, it just blew me away. I definitely haven’t been getting enough sleep, because I haven’t been able to put it down!

The adventure is convoluted, the personalities ever more compelling, the confrontations fizzing with action. I dare to say that this is the best extended fantasy tale I have ever read, with this trilogy being the perfect conclusion, and I know I will return to it someday to re-experience the pleasures of this exquisitely detailed saga.

I am somewhat consoled for its ending by the fact that there are other books by Hobb set in this universe, including The Liveship Traders books and the Rain Wild Chronicles. I am reluctantly pulling away from it for a while, because I need to read and review more for this blog after having neglected it so shamelessly for weeks while I indulged my fantasy binge. But I will definitely go there sometime in the near future.

More Robin Hobb

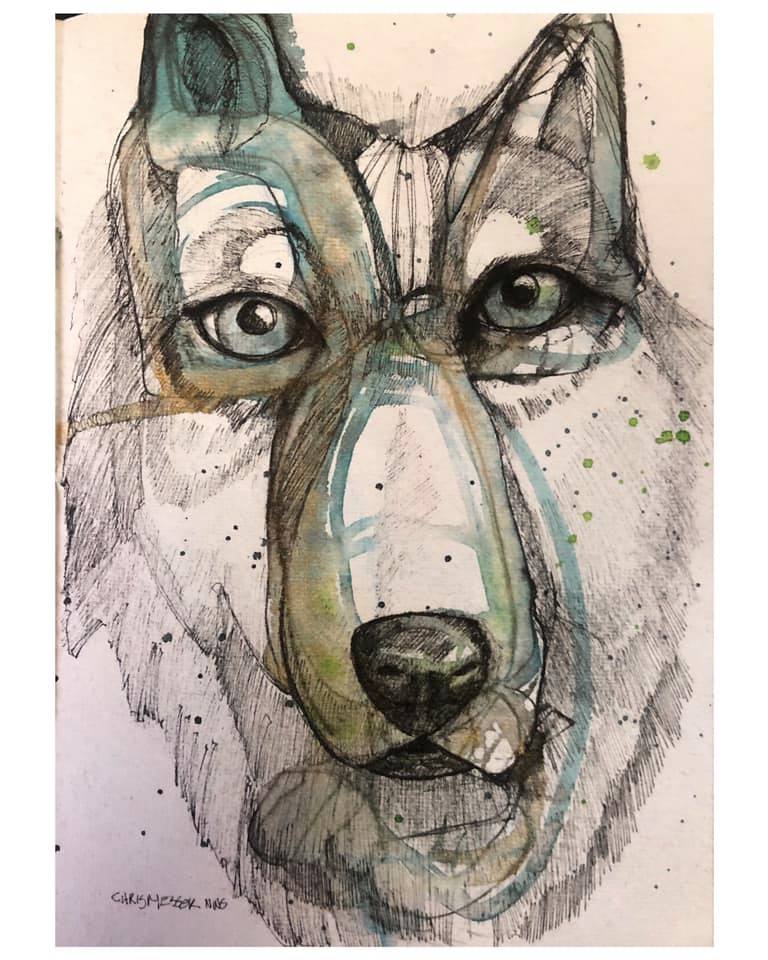

In The Tawny Man trilogy, we pick up with FitzChivalry, royal bastard and secret assassin for the rulers of the 12 Duchies, 15 years after the events of the third book in the Farseer trilogy. Fitz and his witted partner, Nighteyes the wolf, have dropped off the grid, spending time traveling and living rough, then finally establishing themselves in a tiny cottage far from the activities of court at Buckkeep. Fitz, who goes by the name Tom Badgerlock since his widely rumored demise, has adopted Hap, a child brought to him by the minstrel Starling, and has raised him with many of the precepts taught Fitz by his mentor, Burrich. The two of them and Nighteyes are living the quiet, mundane existence that Fitz craved after the tumultuous events of the first part of his life were finally concluded successfully; so when Chade, the royal assassin who taught Fitz his trade, shows up at his cabin to ask him to return to Buckkeep and take up former responsibilities, Fitz isn’t interested. But following his visit, Fitz’s friend the Fool arrives and continues his argument by reminding Fitz that the Fool is the White Prophet and Fitz is his Catalyst, and their partnership is necessary to effect change.

I can’t describe the myriad details of the rest of the trilogy here for two reasons, one being that there are too many important and complex events to explain in a short format such as this, and the other being that I wouldn’t spoil this saga for anyone for the world. But it is the relationships that dominate these books and make it well worth investing your time in this lengthy (2,000+ pages) tale. The connections between Fitz and Nighteyes, Fitz and Prince Dutiful, impulsive heir to the Farseer throne and, most of all, Fitz and the (former) Fool are so rich and compelling that the pages fly by. The introduction of new elements to the story—the OutIslanders and the potential for a union with the Six Duchies through the marriage of Dutiful to their narcheska, Elliania; the “half-wit” serving boy, Thick with his tremendous Skill talent; the charismatic Witted leader, Web; and most of all the enigmatic Lord Golden are equally fascinating, as are the old and new locations in which all events transpire.

If you read and loved the first trilogy, this one will convince you that Robin Hobb is one of the greats when it comes to fantasy sagas. The books are Fool’s Errand, Golden Fool, and Fool’s Fate.

After reading this, I went back to the Cork O’Connor mysteries, by William Kent Krueger, about which I will report on soon; but no sooner had I finished the third of those than I sought out trilogy #3, The Fitz and the Fool, to complete my knowledge of FitzChivalry and his White Prophet. And there are more stories set in this universe, after these!

Immersed in fantasy

I don’t know how I have been a fantasy reader for so many years without discovering Robin Hobb. Someone mentioned her to me lately, and I went looking to find out more. I am now caught up in a prolonged pursuit of everything I have missed.

My first incursion was into the world of The Assassin’s Apprentice. Born on the wrong side of the blanket, the Bastard, as he was first called, was brought to the court of the Six Duchies by his maternal grandfather and dropped off to be raised by his father’s people. Turns out he was the illegitimate offspring of the King-in-Waiting, Chivalry, who was such an upright man that the humiliation felt by this revelation of his youthful misdeed caused him to abdicate his place in the succession for the throne. King Shrewd’s second son, Verity, became King-in-Waiting, while his third son (by a different mother) Regal fumed at the denial of what he saw as his rightful place.

But this story, while intimately tied up with all these royals, is about the Bastard, the Boy, finally and somewhat casually called FitzChivalry. Initially he plays no important role in the life of the kingdom; he is farmed out to the master of horse, Burrich, to raise, and Burrich thoroughly educates him in such skills as how to groom a horse and muck out a stall. During this sojourn as an invisible stable boy, Fitz discovers an affinity he accepts as a natural part of life, although others don’t seem to possess it—the Wit. He has the ability to bond with animals, to hear their thoughts and chime with their emotions. This is a talent that was once valued but at some point in history came to be regarded with abhorrence. But before Fitz becomes completely submerged in the life of the stables, it is suddenly decided that he will be called upon to take a more active part in the politics of the kingdom. He is summoned by King Shrewd and pledged to the royal family, and thus begins his training in scribing, weaponry, and the art of the assassin, the secret vocation for which he is apparently destined.

That is the trajectory established in book #1 of this trilogy. Book 2 shows Fitz completing difficult tasks in his new role, while acquiring a bonded partner in the abused wolf Nighteyes, and a potential life partner in the candlemaker, Molly, friend from his youthful forays down to the docks and now a serving girl to the new Queen-in-waiting. But the relentless decimation of the Six Duchies by the Red Raiders from the sea combined with the depredations of Regal on the kingdom while Verity is preoccupied with defending it by use of the Skill (a gift of mind communication and manipulation that is both seductive and draining of its user) put Fitz in a dangerous and exposed position that ultimately spells disaster for him. The third book sees him desperately seeking Verity, who has departed for the mountains on a quest to seek aid from legendary beings called Elderlings, leaving his court to be usurped by a triumphant Regal, who squanders its resources and leaves half the kingdom exposed and undefended. The success of Verity’s quest is highly doubtful, but Fitz, King Shrewd’s Fool, and the young queen, Kettricken, can see no alternative but to follow and aid him if it’s possible.

put me so in mind of the wolf Nighteyes that I begged her to let me feature it in my review of Hobb’s books.

This summary, though seeming fairly detailed, leaves out about 80 percent of the tale Hobb spins in this trilogy, and is completely inadequate to convey the complexity of the world-building, the delineation of the charismatic and fully formed characters, and the emotions invoked by this involved and mesmerizing story. The trilogy held me captive, and although I read two other (unrelated) books after it, I was constantly pulled back to wonder about what happened next to Fitz, the Fool, Kettricken, Chade, Molly and Burrich, and all the rest. So as soon as I had finished those books, I lined up the next two trilogies—The Tawny Man, and the Fitz and the Fool series—on my Kindle, and started in. Since each book is between 600-700 pages, this may take me a while! But immersing myself in this world is a great way to pass a month of summer!

The Thief Returns

I’m going to start by saying

I don’t really know how to write a review of this book, because I am so predisposed to love it. I discovered the Queen’s Thief series, by Megan Whalen Turner, about 12 years ago when I became a teen librarian and found it in the library’s young adult book collection, and have been raving about it ever since.

Just to clear up what I think of as grievous misperceptions, I’m first going to say that this is not a young adult series. That is not to say that young adults—or even younger children, if they are bright, perceptive readers—would not appreciate it; but this is not a series that was designed specifically to appeal to the YA market like such others as Sarah J. Maas’s A Court of Thorns and Roses (ACOTAR), to which it has superficially and mistakenly been compared by publishers desperate to sell books. The Queen’s Thief books are both expertly and lyrically written to appeal to absolutely anyone who loves fantasy (and, probably, if you could get them to read it, to those who don’t). It is brilliantly crafted (which I will discuss further below) and in no way deserves to be dismissed as suitable only for a certain demographic.

In fact, I feel like the initial publisher did the series a grave disservice by packaging and selling it to children. The first two covers of The Thief, put out respectively by Greenwillow and Puffin, were designed with a Percy Jackson vibe to appeal to 4th-graders, and it’s a miracle anyone else ever discovered it.

Fortunately, by the third release Greenwillow got it right, and the next three books came out with similarly engaging, nicely illustrated covers that would appeal to both teens and adults. Unfortunately, the long hiatus (seven years) between books four and five meant a re-design and a re-release in hardcover, with completely new art, so the only way for people who are obsessive about their series being all the same size with the same cover art is to buy the entire six-volume set over again. (I probably won’t do that, considering that I prefer the original covers, but it is a little annoying.)

The second thing I’d like to clear up is that the aforementioned desperate publishers keep insisting in their blurbs that the books in this series are stand-alone. They are not. If you do not read them all, and read them in order, you will be utterly and completely lost as to what is happening, to whom, and why. What the publishers don’t understand is that this is actually a huge advantage, because the books are so compelling that I daresay a large percentage of those who begin with The Thief are guaranteed to continue. And the true advantage of that, in my opinion, is that the books become exponentially better with each one, up through book #4. (I am not saying that to disparage books five and six in any way, but the story shifts at book five to a somewhat unrelated segue of a tale, and comes together again in book six to conclude things properly.)

Each of the books has a different narrator, which serves two purposes: One, it gives the reader a more well-rounded and broader perspective of the tale as a whole, seen as it is through multiple viewpoints with differing roles and agendas; and two, it keeps the story fresh and interesting. And those narrators are by no means limited to the primary protagonists; book #3 (The King of Attolia) is narrated by a hitherto unknown soldier; book #4 (A Conspiracy of Kings) by a character who, though vital, was only superficially explored in book #1; book #5 (Thick as Thieves) by a slave of the Mede empire; and book #6 (Return of the Thief) by the mute, disabled son of one of Eugenides’s greatest enemies. Who but Megan Whalen Turner would have the nerve, or the brilliance, to pull that off?

How to describe this series? Especially without giving away the cleverness, the hidden agendas, the STORY….

In the simplest of terms, this is the tale of three kingdoms—Attolia, Eddis, and Sounis—and their rulers, which exist a bit uneasily side by side on the Little/Lesser Peninsula, and what happens to and within each/all when they are threatened by the mighty Mede empire with annexation. It has a vaguely Greek or Eastern flavor, particularly as regards its gods and traditions, which is a nice shift from a more usual swords-and-sorcery Medieval-type theme. There are political machinations and plots, love, heartbreak, and courage. There are relationships so complex they take the entire series of six books to understand. There are occasional interventions by the gods, betrayals by those seemingly beyond reproach, and personal relationships between the mighty and the small that endear both to the reader. There are wars, including battles both literal and emotional for the soul of the countries, those of its rulers, and to win over some of its lowliest subjects. Dare I say it has everything?

It took Megan Whalen Turner 24 years to write the entire thing. The books are not, however, gargantuan collections of names and facts and histories akin to a Game of Thrones with its over-the-top, kitchen-sink 700+-page tomes. Instead, each book is a perfect jewel of between 300-400 pages that tells everything it should to further the story, but nothing more and nothing less. It took her an average of four years (one took six, one seven, and one three) to write each one and, I have no doubt (having read the series multiple times) that she considered each and every word, sentence, thought, feeling, and event carefully before adding it.

They say that the test of a good book or series lies in the ability to reread it and have something new revealed with each experience; I have read the first four books either three or four times apiece, and book #5 twice, the second time as a bridge to the end volume. For me, however, rereading isn’t just about picking up things I missed the first time, it’s the joy of reconnecting with something that touched me profoundly—a reunion with the world in all its details, with the subtleties portrayed by its characters, with the humor, the emotion, the realness of it.

That end volume brings us full circle to the quandary that was set up near the beginning and then proceeds to solve it, not without cost but with perfect satisfaction. This doesn’t mean that it is an easy glide down to the conclusion, however; this part of the tale is as full of surprising plot twists as is the first, and the reader is beguiled anew by all of its actors, especially the unfathomable, mercurial, and yet completely engaging Eugenides. And while it is bittersweet to reach the end, I have no doubt that I will return to this story and these characters at least a few more times to relive the entire experience.

Have I convinced you to read it?

Significant relationships

I picked up The Marsh King’s Daughter, by Karen Dionne,

with the misconception that it would be a fantasy retelling of an obscure fairy tale. But although the author makes creative episodic use of the Hans Christian Andersen story of the same name by revealing it gradually in chapter headings, the tale told here is all too real.

Helena Pelletier is revealed as a former “wild child,” one of those who has been raised in the wilderness outside of society, under no one’s influence but that of her parents. Even that statement is misleading; her mother played no real role (except that of passive housekeeper and provider of meals). Her Anishinaabe nickname, given to her by her part Native American father, was Little Shadow, and Helena became, as she grew, a miniature version of him, learning all he was inclined to teach her—including a basic disdain for her weak and ineffective mother. Under his tutelage she learned to track, trap, hunt, gather, and survive in the combination of forest and marshland in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan where their cabin was situated.

The truth that she finally discovers at age 12 rocks her world and skews all her perceptions: Her father kidnapped her mother off the street when she was 14 years old, brought her to his cabin in the marsh, and held her prisoner. At age 16 she became pregnant and gave birth to Helena, who spent the next 12 years in ignorance and freedom, being raised by the victim and her captor.

The story is compellingly told in alternating chapters of present day and past tense. After eluding arrest for two years, Helena’s father spent 13 years in prison for his crimes. But now he has managed to escape, killing two guards and supposedly heading off into the heart of a wildlife refuge. But Helena, now in her late 20s and with a husband and two daughters of her own, knows him well enough to believe that this is misdirection to get the manhunt going in that area while her father will make his way to the land he knows best, part of which is now the site of Helena’s family home. She also believes that since no one knows him and his skills the way she does, she is the only one who can track him down.

Each revelation in the present day leads to a chapter about her life in the past, and as the book moves to its conclusion, the picture of what that was like grows deeper, broader, and more fascinating. This is a cat-and-mouse thriller full of suspense: Although we know from the outset that Helena’s father is “the bad guy,” the tension of seeing how her life plays out as she grows up and becomes self-aware enough to recognize him for who he is—a dangerous narcissist, a psychopath—gives agency to some truly compelling character development. The conflict experienced by Helena, who goes from idolizing her father to questioning his authority to the major revelation of his actions, followed by an uncomfortable and protracted adjustment to her new life in society, shows all the nuances of parent-child relationships and how they help and harm as children achieve adulthood. I’m so happy to finally have read a book this year that I can unequivocally endorse! Five stars from me.

One of the attractive parts of this story is the wealth of detail about the marshes and wetlands of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan in which it is set; but I should also note that there is a fair bit of detail about the trapping and killing of animals for food that may disturb some readers. I am a vegetarian for compassionate reasons and managed to get through it, but some of it was more graphic than I would have liked.

Libraries, booksellers…

So, on the Facebook page “What Should I Read Next?” a lot of people have been touting the book The Midnight Library, by Matt Haig, as a really good read. I took note because, as you know if you read this blog, I love books about books and reading, plus I’m a former librarian. Also, the description sounded intriguing! So the next time I had a break in my reading schedule, I remembered that there was a book about books that I wanted to read, and…I somehow ended up with The Left-Handed Booksellers of London, by Garth Nix.

It’s on my Kindle, which The Midnight Library is not; but I’m pretty sure that I have a physical copy of that book floating around my house somewhere (although I may have confused it with The Librarian of Auschwitz, which is definitely in my living room pile), so I will get to it. But in the meantime…Garth Nix!

I have several friends who are huge fans of Garth Nix, particularly of his Abhorsen series that begins with the book Sabriel, and also the series containing The Keys to the Kingdom. I have picked up the book Sabriel several times meaning to read it, and then put it down again, because the whole necromancy theme doesn’t, in general, appeal to me. But people whose reading tastes I trust have consistently raved about him, so last year I purchased his YA book Newt’s Emerald as a remainder from Book Outlet. The description roped me in because Nix said he was inspired to write this historical fiction based in Regency England by one of my absolute faves, Georgette Heyer. And he got all the details right, plus he added magical elements, but…there are some books that—no matter how much you enjoy them in the moment—are just not memorable. There was absolutely nothing wrong with the book, but the things that were right with it were not quite enough. I liked it, it was cute, it was mildly entertaining, and…that’s it. So I wasn’t sure, when I started Left-Handed Booksellers, of what my experience would be.

I can definitely say that I liked it much better than I did Newt’s Emerald. There were several things that made it instantly appealing. First, it’s a “quest” book. The protagonist, Susan, is enrolled in art school for the fall semester in London, but decides to come a few months early, for several reasons: She wants to scope out her new surroundings, having visited London before but never lived there; she wants to try to pick up some work waitressing in a café to put some extra spending money by for the school year; and, last but not least, she wants to find her father. Her mother, an exceedingly vague lady whose manner most assume is the result of an excessive intake of drugs during the 1960s, has never told her who her father is, and in fact Susan isn’t positive Jassmine even knows for sure. But Susan, with a keen desire to find out, has written down a list of men her mother has mentioned over the years, and has collected a few artifacts that might be related to him in some way, and she is fully prepared to play detective.

Unfortunately, her first research foray is not only unsuccessful, but lands her in the middle of a situation with which she is not prepared to cope. The first man on her list was a vaguely gangsterish fellow named Frank Thringley, who used to send her a birthday card every year, but before she can question him, he is turned to dust by an exceedingly handsome young man wearing a glove on his left hand like Michael Jackson. Merlin turns out to be a left-handed bookseller, and explains to Susan that along with the right-handed ones, he is part of an extended family of magical beings who police the mythic and legendary Old World when it intrudes on the modern world, in addition to running several bookshops. This is the second thing that makes the book appealing: It is full of beguiling concepts and characters that all hang together to make a plausible, if not entirely logical, alternate London, offering constant surprises as you continue to read.

Susan has drawn unwanted attention from the wrong people, both human and otherworldly, with her mere presence at the death of Thringley, and discovers that her best bet is to stick with Merlin and his sister, the right-handed Vivien, to gain some protection and some aid from the booksellers, while trying to find her father and, incidentally, helping the siblings with a quest of their own.

Although the main and two subsidiary protagonists in this tale are all around 18 years of age, I would not necessarily characterize this book as Young Adult, although I’m sure it would appeal to any teenager who likes fantasy. But I think it would equally appeal to any person who likes fantasy, regardless of age. It’s briskly paced and intelligently written, and immediately engages you in the story, which is full of fanciful descriptions of all the old-world denizens. There are lots of adventures, mysteries, and surprises contained within its pages, and it comes to a satisfying conclusion while leaving the door open for more possible stories about the booksellers of London, which I, for one, would welcome.

I don’t know how it stacks up to Sabriel, but based on my enjoyment of this book, I may decide it’s worth my while to find out someday.

2020 Faves

I don’t know if anyone is dying for a reprise of my favorite books of 2020. Since I am such an eclectic reader, I don’t always read the new stuff, or the popular stuff. Sometimes I discover something popular three years after everyone else already read it, as I did The Hate U Give this past January (it was released in 2017). Sometimes I find things that no one else has read that are unbelievably good, and I feel vindicated by my weird reading patterns when I am able to share it on my blog. But mostly I just read whatever takes my fancy, whenever it comes up and from whatever source, and readers of the blog have to put up with it.

Anyway, I thought I would do a short summary here of my favorite reads for the year, and since they are somewhat evenly populated between Young Adult and Adult books, I will divvy them up

that way.

YOUNG ADULT DISCOVERIES

Fantasy dominated here, as it commonly does, both because fantasy is big in YA and because I am a big fantasy fan. I discovered a stand-alone and two duologies this year, which was a nice break from the usual trilogy and I think worked better for the authors as well (so often the middle book is weak and the last book is rushed in those cases).

The first was The Hazel Wood and The Night Country, by Melissa Albert, and although I characterized them as fantasy, they are truthfully much closer to fairy tale. I say that advisedly with the caveat that this is not the determinedly nice Disney fairy tale, but a real, slightly horrifying portal story to a place that you may not, in the end, wish to visit! Both the story and the language are fantastic, in all senses of the word.

The stand-alone was Spinning Silver, by Naomi Novik. The book borrows a couple of basic concepts from “Rumpelstiltskin,” turns them completely on their heads, and goes on with a story nothing like that mean little tale. There are actual faerie in this book, but they have more to do with the fey creatures of Celtic lore than with any prosaic fairy godmother. It is a beautifully complex, character-driven story about agency, empathy, self-determination, and family that held my attention from beginning to end.

The second duology was The Merciful Crow and The Faithless Hawk, by Margaret Owen, and these were true fantasy, with complex world-building (formal castes in society, each of which has its own magical properties), and a protagonist from the bottom-most caste. It’s a compelling adventure featuring good against evil, hunters and hunted, choices, chance, and character. Don’t let the fact that it’s billed as YA stop you from reading it—anyone who likes a good saga should do so!

I also discovered a bunch of YA mainstream/realistic fiction written by an author I previously knew only for her fantasy. Brigid Kemmerer has published three books based on the fairy tale “Beauty and the Beast” (and they are well done), but the books of hers I fell for this year were about typical teenagers with problems that needed to be solved and love lives that needed to be resolved. My favorite of the four was Letters to the Lost, but I also greatly enjoyed More Than We Can Tell, Thicker Than Water, and Call it What You Want.

These were my five-star Young Adult books for 2020.

ADULT FICTION

As YA selections were dominated by a particular genre, so were my books in Adult fiction, almost all of them falling in the mystery section. But before I give you that list, I will finish up with fairy tale by lauding an original adult story that engaged me from the first page and has stuck with me all year: Once Upon A River, by Diane Setterfield. The fairy tale quality is palpable but the archetypal nature of fairy tales doesn’t dominate the story, which is individual and unique. It is the story of three children and the impact of their disappearances (and possible reappearance) on the people close to them, as well as on the inhabitants of one small town beside the river Thames who are caught up by chance in the events that restore a child to life. But the story encompasses more than her fate: It gives extraordinary insight into the issues of life and death—how much they are worth, how they arrive, how they depart, and what is the best way to pursue them.

Another book I encountered in 2020 that didn’t fall into the mystery genre or belong to a series was the fascinating She Rides Shotgun, by Jordan Harper. This was a short, powerful book by a first-time author, a coming of age story set down in the middle of a dark thriller that bowled me over with its contradictory combination of evil deeds and poignant moments.

And the last stand-alone mainstream fiction novel I enjoyed enough to bestow five stars was Just Life, by Neil Abramson. The story showcases the eternal battle between fear and compassion, and involves a deadly virus and a dog shelter in a fast-paced, gripping narrative that takes over the lives of four people. It made me cry, three times.

Most of the mysteries I enjoyed this year came from a “stable” of staple authors I have developed over the decades and upon whom I rely for at least one good read per year. The first is Louise Penny, whose offering All the Devils Are Here in the ongoing Armand Gamache series is nuanced, perplexing, and utterly enjoyable, all the more so for being extracted from the usual Three Pines venue and transported to the magical city of Paris.

Sharon J. Bolton is a reliable source of both mystery and suspense, and she didn’t disappoint with The Split, a quirky story that takes place over the course of six weeks, in stuffy Cambridge, England, and remote Antarctica. Its main character, a glaciologist (she studies glaciers, and yes, it’s a thing) is in peril, and will go to the ends of the earth to escape it…but so, too, will her stalker, it seems. The Split is a twisty thriller abounding in misdirection, and definitely lives up to Bolton’s previous offerings.

Troubled Blood, by “Robert Galbraith,” aka J. K. Rowling, is my most recent favorite read, and is #5 in that author’s series about London private detective Cormoran Strike and his business partner, Robin Ellacott. It’s a police procedural with a lot of detail in service of both the mystery and the protagonists’ private lives, it’s 944 pages long, and I enjoyed every page.

Finally, this year i discovered two series that are new to me, completely different from one another but equally enjoyable.

The first is the Detective Constable Cat Kinsella series by Caz Frear, which currently encompasses three books. I read the first two earlier in the year and promptly put in a reserve at the library on the third (which had yet to be published at the time), and Shed No Tears just hit my Kindle a couple of days ago. They remind me a bit of Tana French, although not with the plethora of detail, and a bit of the abovementioned Sharon Bolton’s mystery series starring Lacey Flint. Cat is a nicely conflicted police officer who comes from a dodgy background and has to work hard to keep her personal and professional lives from impinging one upon the other, particularly when details of a case threaten to overlap the two. I anticipate continuing with this series of novels as quickly as Frear can turn them out.

The second, which is a mash-up of several genres, is Charlaine Harris’s new offering starring the body-guard/assassin Gunnie Rose. I read the first two books—An Easy Death and A Longer Fall—this year, and am eagerly anticipating #3, coming sometime in 2021 but not soon enough. The best description I can make of this series is a dystopian alternate history mystery with magic. If this leads you to want to know more, read my review, here.

These are the adult books I awarded five stars during 2020.

I hope you have enjoyed this survey of my year’s worth of best books. I am always happy to hear from any of you, and would love to know what you found most compelling this year. I think we all did a little extra reading as a result of more isolation than usual, and what better than to share our bounty with others?

Please comment, here or on Facebook, at https://www.facebook.com/thebookadept. Thanks for following my blog this year.