Constructive maundering

This week my breakfasts were beguiled by a book I have meant for some time to read: Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog), by Jerome K. Jerome. You may or may not have heard of it; although it is considered a classic, it’s not the kind typically assigned as part of a high school curriculum. Nonetheless, as Wikipedia cites, “The book, published in 1889, became an instant success and has never been out of print. Its popularity was such that the number of registered Thames boats went up 50 percent in the year following its publication, and it contributed significantly to the Thames becoming a tourist attraction. In its first 20 years alone, the book sold over a million copies worldwide.”

I only know about it because I am a science fiction fan(atic), and a reader of the books of Robert Heinlein and Connie Willis. Three Men in a Boat is mentioned in Heinlein’s Have Spacesuit—Will Travel, wherein it inspired Willis to read it and then title one of her time travel series To Say Nothing of the Dog, the actions in that book being a loose tribute to the original.

I have mentioned Willis’s book here before, describing it as a sort of French farce featuring a hapless cast of misfits and, now having read the original inspiration, I can see even more clearly where the frenetic, chase-your-tail style in which Willis wrote her book originated. Three Men is chock full of the most hilarious minutiae of everyday life, not to mention the mental maunderings of its narrator, who wanders away from each topic to discuss the most useless and suspect bits of information, only to eventually work his way back again to the original subject, pulling himself up and getting on with the narrative.

It’s not exactly a story, per se; its main protagonist and first-person voice, “J.,” is more concerned with travelogue—commenting on points of interest as the boat advances up the Thames—coupled with self-indulgent flights of fancy about Man and Nature and the recounting of numerous ridiculous anecdotes about his fellow travelers, his dog, random bartenders and fishermen he has encountered during his life, and so on. He will ramble on about the next stop along the river—its history and monuments, what events transpired, who slept in what public house and which one now stocks the best ale, who is buried there, etc.—and then comment about the petty details of their day on the boat—who inadvertently dragged whose shirt through the water, what food they had to eat and its effect on their mood and/or bowels—interrupting all this once in a while to recount a close call with a launch or a ferry, a hang-up of their boat inside one of the river’s locks, and then switching to laudatory ravings about nature…and so it goes for about 185 pages.

An example of the flowery language he uses when making his observations about the natural world:

“Sunlight is the life-blood of Nature. Mother Earth looks at us with such dull, soulless eyes, when the sunlight has died away from out of her. It makes us sad to be with her then; she does not seem to know us or to care for us. She is as a widow who has lost the husband she loved, and her children touch her hand, and look up into her eyes, but gain no smile from her.“

One reviewer on Goodreads remarked that the book is abrupt and atonal, what with the author occasionally forgetting that he’s writing a comic novel to come out with these paeans and flights of fancy but, for me, that’s the fun of it, the whimsical British humor.

The account, once they have made their decision to go on holiday on the Thames for a fortnight, is completely driven by the sights they see and the stops they make up the river, so one can see why the book was popular when first published and how it generated so much interest in boating as a tourist activity; people would naturally want to observe all these things for themselves. But 135 years later, although some of the landmarks will retain their ruins and their burial grounds, all else will have changed enough to be unrecognizable, so the pleasure in reading Three Men in a Boat becomes more nostalgic than anything else.

I must say, however, that the humor with which Mr. Jerome tells his tale is so engaging that I actually saved bits to read out loud to my cousin when she came by the other day. He has a way of having his protagonist say something so that you don’t know whether it is meant for him to be serious or tongue in cheek; it’s hard to pull off being ironic and gently making fun of your characters but at the same time presenting them and some of their views in all seriousness. I laughed out loud a few times.

Here’s an example: They had just finished eating supper, which they really wanted after a long day of rowing.

“How good one feels when one is full—how satisfied with ourselves and with the world! People who have tried it, tell me that a clear conscience makes you very happy and contented; but a full stomach does the business quite as well, and is cheaper, and more easily obtained. One feels so forgiving and generous after a substantial and well-digested meal—so noble-minded, so kindly-hearted.

“It is very strange, this domination of our intellect by our digestive organs. We cannot work, we cannot think, unless our stomach wills so. It dictates to us our emotions, our passions. After eggs and bacon, it says, “Work!” After beefsteak and porter, it says, “Sleep!” After a cup of tea, it says to the brain, “Now, rise, and show your strength. Be eloquent, and deep, and tender; see, with a clear eye, into Nature and into life; spread your white wings of quivering thought, and soar, a god-like spirit, over the whirling world beneath you, up through long lanes of flaming stars to the gates of eternity!”

(I don’t know about you, but I don’t think I have ever been quite that inspired by a cup of tea!) He then goes on for another entire paragraph delineating the effects of muffins, brandy, and so on, and concludes with this thought:

“We are but the veriest, sorriest slaves of our stomach. Reach not after morality and righteousness, my friends; watch vigilantly your stomach, and diet it with care and judgment. Then virtue and contentment will come and reign within your heart, unsought by any effort of your own; and you will be a good citizen, a loving husband, and a tender father—a noble, pious man.”

And thus it goes, with the conversation moving from the positive effects of a good meal to the discussion of whether they would be happier away from the world living on a desert island, to fears about damp and drains, to the recounting of an anecdote about sleeping in the same bed with a stranger at a crowded inn…

This book is not one I would unreservedly recommend that everyone should read, but it has a certain reminiscent air for me of the beloved antics of Bertie Wooster, Jeeves and Co. in the tomes of P. G. Wodehouse and, if you like that kind of story where the characters are disingenuous and rather simple-minded while the writing itself is quite clever, then you might enjoy Three Men in a Boat. But even if you don’t read it, do have a go at To Say Nothing of the Dog, by Connie Willis.

Fictional memoir

A Piece of the World, by Christina Baker Kline, is in a special category: Although the overall story is fiction, it is based on facts about real people, and reads like memoir.

The book is based on Andrew Wyeth’s painting called Christina’s World, pictured here. People have always noticed something slightly odd about the figure in this one—she’s not just reclining in that field, she looks like she’s wanting to get to that house, or perhaps even pushing or dragging her body along in the attempt. This is the germ of the idea for the entire book, which, although it does showcase some of Wyeth’s career, is primarily about the subject of the painting, Christina Olson of Cushing, Maine.

The book documents Christina’s entire life, which turns out to be a small one except insofar as she serves as muse to the famous painter. Christina suffers some kind of illness at age three (they never state what, but my thought was polio) that twists her legs up and makes her awkward and clumsy in all her movements. This and her own pride and self-reliance make her an outsider, both in her family and in her community, with the result that the chances others have for happiness seem to pass her by, no matter how hard she tries to grasp them. She grows up in the house previously occupied by generations of her ancestors; she cares for her brothers and her aging, ailing parents as her disability gradually worsens; and she is finally left with one brother to live out her days in an ever-diminishing daily routine circumscribed by her physical condition…until one day Andrew Wyeth’s young wife, Betsy, a family friend, brings him to visit, and he becomes fascinated with Christina, her brother Alvaro, and their house and farm in all its aspects. No detail is too large or too small for him to tackle in his art—he paints the rusty padlocks and spiderwebs, the sheer curtains blowing in the breeze from an upstairs window, Alvaro smoking his cigar—and this begins an almost 20-year relationship between himself and the two remaining Olsons, resulting in possibly his most famous picture/portrait.

“Later he told me that he’d been afraid to show me the painting. He thought I wouldn’t like the way he portrayed me: dragging myself across the field, fingers clutching dirt, my legs twisted behind. The arid moonscape of wheatgrass and timothy. That dilapidated house in the distance, looming up like a secret that won’t stay hidden.”

CHRISTINA OLSON

In some ways this is a dark, dour portrayal, but it is rescued from being too depressing by Christina’s will and strength of spirit, and by wanting to know what happens next. The book deals with complex issues; resentment, shame, lost dreams, family challenges, and social classes are explored, and the writer makes us realize that there is depth and intensity to even such a simple existence devoid of major events. There are some fine lyrical moments of expression, and Kline paints pictures with the words she chooses. I didn’t expect to like this book as much as I did—it kept me reading through one sleepless night, and I was a little sorry when it ended. It’s a great example of what an author can do with the kernel of a story, some thorough research, and a vivid imagination to bring them both to life.

A classic based on a classic

I feel like I need some kind of reward for having finished, just as the author deserves an award for having written! I enthusiastically and optimistically started Demon Copperhead, by Barbara Kingsolver, two days after Christmas, thinking it would be my first read of 2023, but my count is now up to 11 books, and I just finished it. I took two breaks, one motivated by wanting to be able to read on my Kindle in the dark of night in my bed (I bought the hardcover of Demon Copperhead, knowing that I’d want to keep it on my shelf), and the other by realizing that the depressing nature of the story was having such a profound effect on my mood that I needed to read something else for a while! But I was determined to finish, and the wink-out of my Kindle battery mid-sentence day before yesterday sent me, finally, back to the last 13 percent of this tangible book.

It’s not that I didn’t want to read it—it’s an amazing story of a quirky, irrepressible, sad, endearing red-headed boy who nobody wants, and it’s also both a literary masterpiece and a stern indictment of America’s marginalization of the disadvantaged. For all those reasons, it is worth my time and yours. But lordy, is it depressing! Damon Fields (the protagonist’s real name) is a logical (though still incredibly unlucky) product of his surroundings, growing up in the foster care system after his junkie mother leaves him an orphan in a single-wide at a young age. But he is not an anomaly—there are plenty of unfortunates in the culture of Southern Appalachia who contribute to the dour mood. One of the most powerful understandings comes towards the end of the book, when Tommy, one of Demon’s former foster brothers, crafts a philosophy of America that pits the “land” people against the “money” people, and the land people—those who hunt and fish, farm tobacco, and share what they have with their family and anyone else in need, operating outside the monetary system—always lose.

I am somewhat ashamed to say that I have never read David Copperfield, the book on which Kingsolver based this one, although I have a fairly good knowledge of its contents and am in awe of how she translated Dickens’s “impassioned critique of institutional poverty and its damaging effects on children in his society” (Kingsolver, Acknowledgments) into this stunning story of the opioid crisis in Appalachia. But unlike the Jodi Picoult novel about which I blogged last, this book is not preaching about the social crisis but instead is determined to tell the story via the victims and survivors of it in a straightforward, completely realistic manner that guts the reader who is invested in them. Every person in this book (and there are dozens) is vivid, individual, and completely memorable. Even though I broke it up into multiple reading sessions over the course of more than a month, I never once had to think, Um, who is this character again? and backtrack, because every single one of them stood out as a person. I can’t think of a much better compliment you could give to a writer, and Kingsolver deserves it.

But it is the character of Demon who dominates—and sometimes overwhelms. His circumstances are beyond tragic, horrifying when you think of a child having to endure what he does, and yet he is a source of continual hope. It’s not that he’s a falsely optimistic Pollyanna of a character, it’s that he has somehow assimilated a work/life ethic that causes him to put his head down and push through every challenge in his desire to live. And even when he fails—and he does that just as spectacularly—he somehow never gives up on himself. As he loses family, friends, mentors, homes, abilities, he manages to continue focusing on what he does have and what he can use, and keeps hauling himself back to his feet.

One reviewer on Goodreads repeated a quote from a Washington Post book review that said,

“Demon is a voice for the ages—akin to Huck Finn or Holden Caulfield—only even more resilient.”

I couldn’t agree more. Another said “This is a book about love and the need for love, the search for love,” and that, too, is true. And the language, both brutal and brilliant—Kingsolver’s way with words is beyond skillful. I won’t say much more about the book, I’ll leave it to you to discover. But it deserves all the accolades.

Openings

Los Angeles Public Library finally let me have The Ten Thousand Doors of January, by Alix E. Harrow, a book about which I had massive anticipation after having devoured Alix Harrow’s second book, The Once and Future Witches (review here). And while that book was about spells hidden in plain sight and this book was about elusive doorways, in a real sense both books are about openings.

The 10K Doors beguiled me from almost the first page. The language was beautiful, evocative, persuasive. The story begins with a book, which is always a way to my heart. And the door theme carried me back to every beloved tale in which someone found an opening to somewhere else and was brave enough to step through it, from the classics (Alice in Wonderland, The Phantom Tollbooth, Narnia) to more recent works (Mirrorworld, Shades of Magic, Un Lun Dun), but it particularly put me in mind of Wayward Children, the stunningly original series by Seanan McGuire that portrays a group of children who have had the experience of going through a portal to the world of their dreams, only to later be ejected and left longing to return. The Ten Thousand Doors of January is the ultimate portal novel.

Like the protagonists in McGuire’s series, January Scaller is a misfit in her own life. Her childhood has been simultaneously comfortable bordering on indulgent, and immensely restrictive; while her widowed dark-skinned father travels on business for his employer, January lives a sedate, smothering life sequestered in Mr. Locke’s mansion that is filled with the artifacts and treasures her father has brought back to him from all over the world. January spends most of her young life torn between gratitude for Mr. Locke’s guardianship and patronage, and resentful that she is kept like another of his precious objects, locked up in a house with no company save for that of a repressive nursemaid/chaperone. As a person of color, January is ogled and patronized by the lily-white British society within which the wealthy Mr. Locke moves (the story begins in 1901), and she has no friends save an Italian grocery delivery boy and the enormous and fanatically loyal dog with whom he gifts her.

As a solitary child, January naturally seeks out ways to amuse herself, and becomes immersed in certain texts and books not meant for her eyes, writings that reveal a possible escape from her overweening patron. But after her father dies and Locke discovers she may have abilities he and his friends value, January must call upon all her thus-far meager resources to save herself from their plans, and also prevent the doorways she has discovered from closing forever.

Books can smell of cheap thrills or painstaking scholarship, of literary weight or unsolved mysteries. This one smelled unlike any book I’d ever held. Cinnamon and coal smoke, catacombs and loam. Damp seaside evenings and sweat-slick noontimes beneath palm fronds. It smelled as if it had been in the mail for longer than any one parcel could be, circling the world for years and accumulating layers of smells like a tramp wearing too many clothes. It smelled like adventure itself had been harvested in the wild, distilled to a fine wine, and splashed across each page.

Although the book has a somewhat slow start, and the protagonist is initially almost frustratingly passive despite her inner nature (“The will to be polite, to maintain civility and normalcy, is fearfully strong. I wonder sometimes how much evil is permitted to run unchecked simply because it would be rude to interrupt it”), the story within a story of Adelaide (Ade) and Yule Ian Scholar (Julian), who find one another when Yule crosses through a door from his home into a Kentucky wheat field, pulls you first into that world and then into the possible connections with January’s, and after that it’s total fascinated attention to the very last page.

This book is almost haunting in its sadness and yearning for the freedom of a wider world, and a longing for the ability to translate otherness into belonging. The loneliness of January, motherless and separated from a father who wants to keep her safe but believes that can’t happen if she is with him; the solitude of Ade, searching relentlessly for the door that will carry her back to Julian; the alienation of January’s friend Jane, exiled from her homeland because of a promise; all act upon the reader to provoke a desperate wish that these people will get what they want, find what they seek, and in that process make the universe a more fluid place.

Doors become more than just passageways to new experiences; they are also symbols of openness and change, qualities that January considers essential while Mr. Locke deems them threatening to existence. Stagnation is antithetical to those who wish for true freedom for everyone, while to the people in power it is an essential component in consolidating their dominance. January is one girl up against a wall of opposition, but she finds unexpected resources from her past, from her few allies, and finally from within. This story connected with my dogged belief, despite the mundanity of everyday life, that there is both magic and hope out there somewhere, if only the way can be found.

It bowled me over.

Genre confused

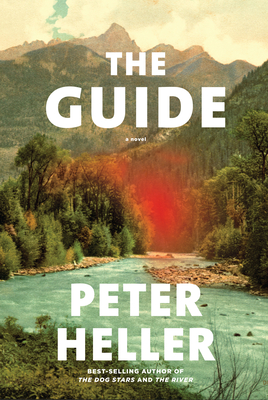

I am a big fan of Peter Heller’s work. I have read all of his novels and haven’t disliked a one of them, although I do have favorites. So I was delighted to discover that he has a “new” book out (almost a year old, now).

The Guide has the trademark lyrical descriptions of nature that one expects from Heller. The theme is fly-fishing, and although I don’t fish and am not a fan of early morning activities, his narrative of the terrain was so lovely that it calmed my breathing as I read it, making me long for wide open spaces with the sound of flowing water in the background and the dawn vista of a still pool with mayflies rising and rings spreading outwards as the sun heats the surface and the fish rise to feed.

Although this book can certainly be read as a stand-alone, it is, in fact, a sequel to Heller’s book The River, in that the protagonist is Jack, a few years on from that tragic adventure. Although it enhanced the experience to know the back story referenced periodically throughout this book, it wasn’t such a direct continuation that anyone would feel the need to go back and review the previous story in order to feel caught up. It’s made plain that Jack has been damaged by an event in his past, and that he sees this term of employment as a guide at one of the most exclusive fishing resorts in the country as an escape from his everyday life, in which he suffers from silence and too much free time.

Jack is taken on by the Kingfisher Lodge, on a pristine stretch of protected waters near the town of Crested Butte, Colorado, to replace a guide who left abruptly. The resort caters to the über-wealthy and the camera-shy celebrity, and provides an all-encompassing interlude of comfortable quarters, gourmet dining, camaraderie, and sport. His first assigned client is Allison K., a woman Jack vaguely recognizes as a hugely famous country western singer (he’s not really into music). She also turns out to be gifted at and dedicated to fly fishing, and the two share what’s described as an almost spiritual out-of-body state as they roam up and down the river, casting their lures.

But there’s something weird going on in this paradise, and soon Jack is nervous and on the defensive as minor violations of some resort rules result in some out-of-proportion reactions and repercussions. He and Allison begin first to speculate and then to research what they’ve been told, as anomalies crop up and their status becomes ever more perilous.

Although I enjoyed this book over all, there seemed to be a profound disconnect between the scene setting and the behind-the-scene activities. Heller’s other books certainly contain elements of mystery and suspense, but for some reason this one didn’t feel organic. For one thing, the “nature documentary” aspect of the book dominates for about 80 percent of the book, with only small hints and incidents thrown in here and there to increase the reader’s feelings of disquiet, and then all of a sudden, in the last 20 percent, it becomes all about the alter ego mystery of the story. Nature buffs will enjoy the setting and melodic language about fishing, while thrill seekers will get their payoff with the bizarre back story, but the genre blending that took place here needed a few more spins of the Kitchenaid to work properly. I was still fairly happy with the book, however, until I reached the last few pages. There are few things I dislike more than a book that shows the entire story, only to punt at the end by “telling what happened” after the significant events occur, instead of taking the reader directly through them, and that’s sort of what happened here.

Primarily as a result of that ending, I would have to recommend Heller’s other books over this one, although the prevailing narrative was the verbal equivalent of the glorious imagery experienced in the 1992 film A River Runs Through It; if you are susceptible to words that so graphically paint a picture, you will enjoy this book no matter what.