Wrapping up

This year it feels more like a winding down than a wrapping up. I read the fewest books in one year since I started doing the Goodreads Challenge 12 years ago. That year I read 75 books; my highest number ever was in 2019, when I read 159 books while working full-time from January to October (I retired from the library in October of that year). You would think it would be the reverse, since I have so much more time now than I did then; but there were some factors at play that ensured I would read a lot more then. First, I was running three teen book clubs, so I had to read one book per month for each club, plus a couple extra books in each age range (the clubs were 6th- and 7th-graders, 8th- and 9th-graders, and grades 10-12) so I would have ideas to propose as the following month’s read. I was also reviewing books for both the teen and adult library blogs (both of which I supervised), so I was heavily invested in spending all my spare time reading new teen and adult fiction to showcase there. And finally, of course, there was a certain amount of reading for my own particular pleasure! I basically worked, commuted, ate, slept, and read, and did absolutely nothing else!

Nowadays there are circumstances that tend to decrease my reading time: With my particular disability, sitting in one position for long periods of time isn’t great for keeping my legs at their best possible condition for mobility. I also watch a lot more on television these days, now that streaming services let you binge-watch an entire five-season show, one episode after another for as long as you can stay awake, as opposed to waiting for one weekly episode for a 12- to 20-week season and then waiting in turn for the following season. And I spend way too much time “doom-scrolling” political stuff online, or keeping up with friends on Facebook. Finally, once I took up painting I started spending at least a few days a week focused on making a portrait or two or a still life featuring items from my antique collection.

Anyway, this year I read a meager-for-me 66 books. Some of them were literary and some of them were chick lit, some were re-reads of beloved stories, and others were authors previously unknown. My statistics include:

23,782 pages, with an average book length of 360 pages

(shortest was 185, longest was 698)

Average rating was 3.6 stars

Some favorite new titles were:

The Unmaking of June Farrow, by Adrienne Young

Starter Villain, by John Scalzi

Vera Wong’s Unsolicited Advice for Murderers, by Jesse Q. Sutanto

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, by Becky Chambers

All the Dead Shall Weep, and The Serpent in Heaven, by Charlaine Harris

Found in a Bookshop, by Stephanie Butland

I felt throughout the year like I was having trouble discovering books that really resonated with me. Although I had some pleasurable reading discoveries, I never found that one book or series or author that really sucked me in and kept me mesmerized for hours at a time. I found myself reading during breakfast or on my lunch break and easily stopping after a chapter or two to go do something else, rather than wanting to settle in for a solid afternoon of reading. I’m hoping to find more compelling books in the new year. But reading continues to be one of my best-beloved pastimes.

Gunnie Rose continues!

At the end of my review of the third book in this series, I devoutly hoped there would be more, and I discovered last week that Charlaine Harris has come through with two more volumes while I wasn’t looking! Imagine my delight at getting to continue this entertaining dystopian historical fantasy mash-up for not one book but two!

You can read my entire review of the first two here, and the third one here, but just to quote myself to give a reaction to those too impatient to do so,

“This series is pure delight, from the elaborate world-building to the laconic Western flavor of Texoma, and the characters are so alive they could step off the page. Harris has written this with just the amount of detail you crave, without drowning you in either description or explanation, and the pace of this mystery/adventure story is perfect. The minute I finished the first book, I jumped without hesitation into the second one.”

You really should read at least my review of the first two, because it gives a thorough description of a rather complicated world-building exercise. But even there, Harris achieves the maximum in understanding with the minimum of detail. She is apparently no more a fan of the info-dump than am I, for which I am thankful.

The fourth book, The Serpent in Heaven, picks up pretty much where the third left off; Felicia is now a school boarder at the Grigori academy in San Diego. She was initially admitted as a sort of honorary student because of the need to keep her safely squirreled away, since she is one of the few blood donors remaining who can save young Tsar Alexei’s life should he have a mishap (he’s a hemophiliac). But in this book, due to some unexpected hazards at the school, Felicia reveals the true scope of her wizardy powers and gets promoted to the “real” classes to learn to control, direct, and expand them, mentored by the curmudgeonly Victor.

This book was told from the first person viewpoint of Felicia herself, which added an extra element to the story, since in the course of her narration you get to know her much better and understand her background, upbringing, and level of skill. Lizbeth (Gunnie) and Eli are mostly missing from this chapter, because they have married and gone off to live in Texoma after the disastrous coup that disgraced parts of Eli’s family in the last book. We get news of them only through an occasional letter or telegram or word-of-mouth message. I thought this would be upsetting to the narrative, but I was completely absorbed in Felicia’s story and didn’t miss them, for the most part, compelling characters though they are.

Harris makes up for this in book #5, All the Dead Shall Weep, when Felicia, accompanied by Eli’s brother Peter, goes to visit Lizbeth and Eli in Texoma, mostly to get away from an ongoing threat of kidnapping by various factions who have figured out her value as a wizard and want to (either voluntarily or forcibly) marry her into their bloodline to amp up their descendants’ talent pool. But bad fortune follows Felicia like a hungry stray dog, and there’s also a new military rebellion beginning to muster, with which the sisters and their men must contend. This book is told by alternating narrators Lizbeth and Felicia, which was initially jarring when I didn’t realize the voice had changed, but actually really helpful in giving all the behind-the-scenes thoughts and feelings you craved from these characters.

And this fifth book ends on a truly ominous cliffhanger, historical in nature, which bodes well for more sequels, though ill for their contents! Still a fan. Check them out!

Dog Day Afternoon

No, this isn’t a post about a 1975 bank robbery movie. But the title seemed appropriate, given that it’s National Dog Day and also that I am getting such a late start that my post won’t be available until after noon, one of those hot, sleepy afternoons when dogs (and people) prefer to lie around and languish (i.e., read!) during the summer heat. I did some pre-planning for this post by making a list of some pertinent dog-oriented books, but then my distracted brain failed to follow up, so a list is pretty much all you’re going to get this time. But don’t discount it just because it’s not elaborated upon; these are some great reads, encompassing fantasy, mystery, dystopian fiction, science fiction, some true stories, and a short list for children.

NOVELS FOR ADULTS (AND TEENS)

The Beka Cooper trilogy (Terrier, Bloodhound, Mastiff),

by Tamora Pierce

A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World, by C. A. Fletcher

Iron Mike, by Patricia Rose

A Dog’s Purpose, by W. Bruce Cameron

First Dog on Earth, by Irv Weinberg

The Companions, by Sheri S. Tepper

The Andy Carpenter mysteries, by David Rosenfelt

The Dog Stars, by Peter Heller

DOGGIE NONFICTION

Marley and Me: Life and Love with the World’s Worst Dog,

by John Grogan

Best Friends: The True Story of the World’s Most Beloved

Animal Sanctuary, by Samantha Glen

James Herriot’s Dog Stories, by James Herriot

A Three Dog Life, by Abigail Thomas

Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know,

by Alexandra Horowitz

CHILDREN’S BOOKS WITH DOGS

Sounder, by William H. Armstrong

No More Dead Dogs, by Gordon Korman

Harry the Dirty Dog books, by Gene Zion

(illustrator Margaret Bloy Graham)

Bark, George, by Jules Feiffer (one of the best for reading aloud!)

And for those who wanted more, here is an annotated list of more dog days books from a previous year, along with some suggestions for dog lovers that go beyond reading about them.

Navola

That was…an experience.

When I was 20 percent in, I actually wrote on Paolo Bacigalupi’s Facebook page that I was enjoying his world-building and the use of language and nuance in his new novel, Navola. (As has been previously commented upon, I am a stickler for authentic world-building.) He responded that he had enjoyed creating them, and I can believe that, because there is a lot of loving detail in this book. As it turns out, maybe too much? At first it reminded me of my best-beloved fantasy series, The Queen’s Thief, by Megan Whelan Turner, and also gave me the feel of Ursula LeGuin’s masterpiece of pseudo-historical fiction, Malafrena. But as it went on, I felt so overwhelmed by the discussion of every niggling detail (and the need to figure out what was meant by all the semi-Italian, sometimes Latin-based lingo) that it almost felt like being back in English class, being forced to read a classic work about which I felt reluctant, since it wasn’t my choice. I couldn’t help but contrast this with Bacigalupi’s excellent Shipbreaker series, in which he masterfully paints the scene using just what he needs, and then jumps full-force into the story.

The world of Navola seems to be based on a loosely historical evocation of city-states from the Italian Renaissance. There is all the intrigue of the Borgias, with both front-facing and behind-the-scenes manipulation of absolutely everyone by everyone else, except by our protagonist, Davico, son and heir to the wealthy and successful merchant banker, Devonaci di Regula da Navola, who is the power behind the titular heads of state of Navola. Di Regulai rules by maintaining a calculated balance between greed and politics, alternately controlling and rewarding his many clients within Navola and in all the surrounding states. But despite Davico’s training in all the arts both physical (knife- and sword-fighting, equestrian, etc.) and mental/political (negotiation, the reading of faces and body language, the subtle acquisition of background information), he remains largely ignorant (or innocent) of the real breadth of knowledge necessary to step up to the challenge presented by his father—to rule Navola as Devonaci has done. Davico is a tragic hero: His honesty and authenticity is a liability in the world to which he has been born, and although he toys with rejecting his heritage, he is not strong enough to stand up to the culture within which he is embedded, nor to the expectations of his father.

Although I have always been a proponent of thorough world-building, I found myself overwhelmed by the sheer volume of the information Bacigalupi attempts to convey throughout this nearly 600-page tome. There are multiple information dumps—my least favorite parts of the book—and even in the course of the sometimes exciting and action-packed scenes, the “behind-the-hand” translations of the language, the explanations about the involved parties, and the setting of context weigh down the actual events to the point where I felt I was constantly digging for the meat of the story.

There is a fantasy element (introduced on the cover by the depiction of a dragon’s eye, an actual artifact Devonaci keeps on his desk in his library), but while its presence is strong in the parts of the story in which it is included, those are few and far between. Its significance to Davico is toyed with early on, and then mostly recedes until near the end of the book, almost past the point where anyone would care.

There is also a grimness to this story that may be disturbing to some; in addition to the mental manipulation, there is no escape from murder, rape, or graphic revenge amidst the noble families’ bloody pursuit of power. It’s not quite as overwhelming as, say, Jay Kristoff’s Nevernight Chronicles, but it has its moments of queasy-making horror.

The real fault I have to find with this book, however, is the complete lack of foreshadowing by anyone—the author, the publisher, Goodreads—that this is merely the opener for a continuing story! I began to realize, at about the 80 percent mark, that this would have to be the case, because the events took such a back seat to the development of the venue itself that there would be no time, unless it was criminally truncated, to resolve the hero’s situation and provide a satisfactory ending, and indeed I was right; it’s one of those cliffhangers where the hero lives to fight another day. It’s not abrupt, but the story is by no means at an end and, if it is, then I would have to say, What was the point of all that? Navola is too well written to give it a bad rating, but if, when perusing the teaser for the book on Goodreads, it had said “volume one,” I would have approached it with a completely different attitude that wouldn’t have left me feeling duped.

Maybe the lack of this was the author’s way of leaving himself an out; if the first book doesn’t go over so well, do you really want to invest the time in writing a sequel? But I am here to say, Paolo Bacigalupi, you owe us all the rest of the story, having made us endure through the laborious stick-upon-stone of the world you built to house it!

Third time continues the charm

I just finished Alix Harrow’s third full-length novel, Starling House, and was nearly as taken with it as I was by her other two (The Once and Future Witches, and The Ten Thousand Doors of January). That’s saying something—if you read my reviews, you will know how blown away I was by every aspect of those two amazing stories.

This one is perhaps not as original an idea as either of the other two; instead, it takes some trope stuff and makes it fresh and interesting. It’s a combination of a Southern Gothic fantasy/horror hybrid and a coming-of-age story, and has a lot of levels.

In some ways it is a commentary on the bigotry and trauma one encounters as an outsider in a small town, particularly a small “company” town in the deep South. This one is Eden, Kentucky, and the town’s reason for existence is the working of the coal mines owned by the Gravely family. The town and its residents are either singularly unlucky or the story of a curse is true, because a sadder and less hospitable place could scarcely be conceived. The supposed origin of the curse is tied up with the history of E. Starling, a 19th-century children’s book author who was married to one of the three original Gravely brothers, wrote a story about a creepy place called Underland, built a mansion for herself after her husband’s death, and ultimately disappeared. Starling House has since been host to a number of owners, all of whom show up just when the previous owner dies or leaves, but such is its unsavory reputation that the people of the town cross the road rather than walk on the sidewalk near its gates.

The book revolves around Opal, a young woman who has never caught a single break. Her mother died in a car crash when she was a child, and she and her younger brother Jasper have continued to live in the motel room where they landed shortly before her death. Opal works a minimum wage job at the local hardware store, trying to save enough money to get her brother, a smart young man with debilitating asthma made worse by the miasma that hangs over the industrial town, into a private high school far from the environs of Eden; but there’s scant hope of that until she gets a job as a cleaner for Arthur Starling. She’s heard all the rumors about both the house and its owner, but she’d do almost anything to get Jasper the chance he deserves in life, so she begins the task of bringing this house full of dust and cobwebs (and other, more sinister things) back to life. But the feeling of sentience she gets from the house and the weird vibes coming off of Arthur, who seems alternatively tortured, coldly aloof, and strangely sympathetic, are getting under her skin, and she’s wondering where it’s all going to end…

You could scarcely find a less likable protagonist than Opal, but she somehow endeared herself to me. Maybe it’s because every small victory she has is so hard-earned that it’s almost not worth it, and you can feel the palpable intensity of her longing for things to change and her simultaneous hopeless conviction that they never will.

The best thing about this book for me was the language. Admittedly, it’s sometimes over the top or overly descriptive, but there are moments that struck me so forcefully that I marked them in my notes on my Kindle. Alix Harrow knows how, with one phrase, to invoke a memory or even an entire phase of life, as with this one, where she is describing some symbols incised into the wood of a door:

The carved symbols are still very slightly luminescent, like glowsticks the day after a sleepover.

I read that one sentence and jumped back to a moment in childhood: We were in someone’s yard at dusk, at the end of a birthday barbecue. We all cracked glowsticks that had been passed out by the birthday girl’s mother, manically waving the neon tubes and dancing around, lighting up the dark. By the next day, most of the chemical inside the sticks had finished its reaction and was subsiding, but there was still a dim glow to them if you turned out the lights in a windowless room.

The biggest flaw in the story for me is the revelation that Opal is 27 years old. Her character, while honestly and intricately drawn, seems more typical of a teenager—16, 17, maybe 18 tops—than of a young woman approaching her late 20s. Honestly, this book works better as a young adult novel, both in its characterizations and in the way the story is couched in a particular kind of gritty magical realism. But since I am a big fan of good young adult literature (note the emphasis on good), that’s fine with me. I simply decided to forget Opal’s age and read it as it reads. There are other problems—unresolved plot points, underutilized characters, unexplained mysteries—but ultimately it all worked for me, with its beautiful prose, interesting characters, and slow-burn sense of menace.

Chefs of the gods

I picked up A Thousand Recipes for Revenge, by Beth Cato, as a bargain book through BookBub. This sometimes indicates that book sales haven’t been that great, but in this case it seems that it was simultaneously published in three formats (paperback, Kindle, and audio book) all on June 1st, so perhaps it was just a promotional gimmick. It’s a fantasy, and as such I found it immediately immersive.

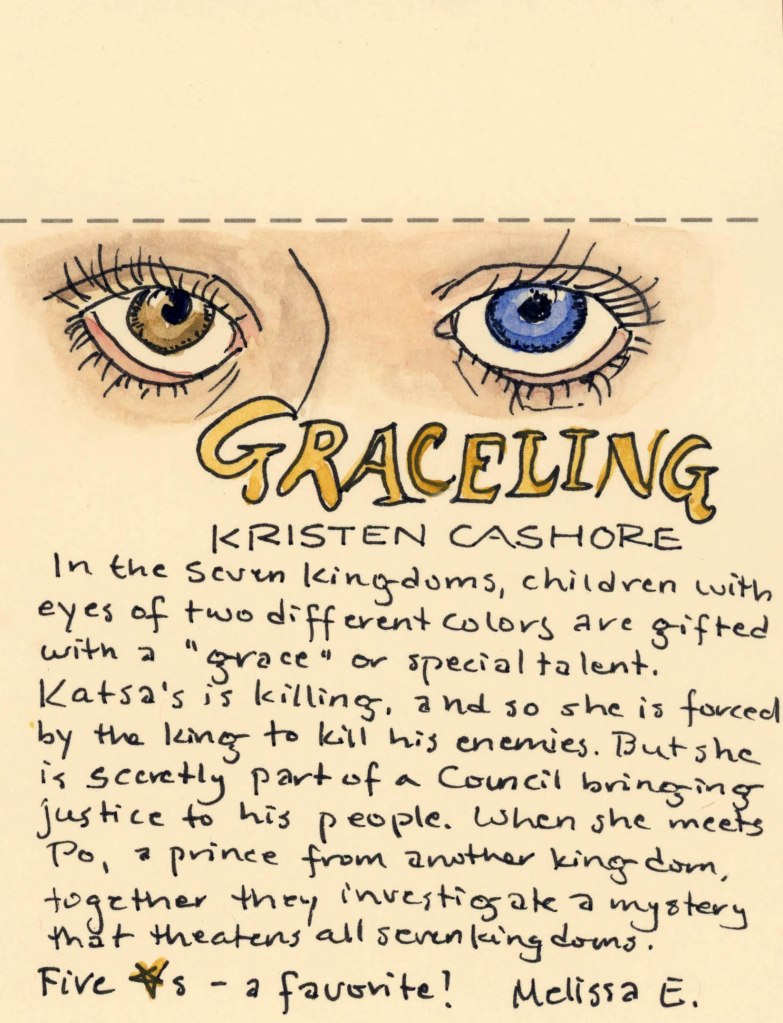

The premise is intriguing: The tag line is “Chefs of the Five Gods #1,” and it’s about people who are born with the special gift of an empathic connection to food and wine—a magical perception of aromas, flavors, and ingredients and, in special cases, the actual ability to intuit what dishes, with what seasonings in kind and quantity, would best please the palate of the diner with whom they are confronted. Needless to say, this ability is highly prized, with the result that while the Chefs, as they are known, are treated like royalty, they are also constrained in their freedom. There are several kingdoms in this story, and in one of them (Verdania) the chefs are “in service” to the gods-ordained rulers of the country, another way to say they are virtual prisoners, not allowed to go elsewhere or work for anyone but the crown. (This is reminiscent of the children born with two different colored eyes and some innate gift in the world of Graceling, by Kristin Cashore.)

The story is told from two points of view, the first being that of Adamantine Garland, who escaped 16 years ago from the position forced upon her, and is living under the radar with her grandmother, both of them rogue Chefs. Since the punishment for abandoning the post of Chef is either death or to lose your tongue (and therefore your gift), they have good reason to take care not to reveal themselves, especially by cooking too well! But circumstances that transpired just before Ada disappeared from the court of Verdania are about to bring her perilously out of hiding.

Solenn is the princess of Braiz, a neighboring land to Verdania, and a marriage has been arranged between her and Verdania’s prince, a 14-year-old boy still more concerned with his friends and amusements than with girls and weddings. It is hoped by the union of these two children and countries that together they will be able to withstand the greater might of another nearby more powerful kingdom, Albion. Something unexpected happens, however, during Solenn’s ceremonious and extended welcome to Verdania—her own magical perceptions awaken (this usually happens at a much younger age), and make her aware that there is a plot by Albion to kill the prince. This unexpected kindling of power (as far as she knows, there are no Chefs in her ancestry) sets in motion several plot twists that will bring together unlikely players in the attempt to save civilization from destructive forces.

I enjoyed the story for several reasons. I liked the world-building: The background felt like a French court from the 17th Century, with musketeers, fancy dress, and court intrigue. But the principle characters who played things out against this backdrop were refreshingly ordinary in their thoughts, actions, and priorities. I liked that there was a wide span of age groups represented in the participants—a few teenagers, some middle-aged adults, and elderly relatives with infirmities that must be regarded. I enjoyed the set-up of the Five Gods of these kingdoms, their various affinities connecting to both food and the greater world (for instance, Selland is associated both with salt and with the sea), and the relationships people maintained with a specific god they considered their patron or guardian. The gods were also refreshingly arbitrary and human in their behavior, which made things more interesting. I enjoyed all the plot twists and, although I’m not sure this was intended as a young adult novel, I felt like this was an example of a book that would appeal equally to teens and to grown-ups who enjoy fantasy. I did not enjoy the somewhat abrupt ending with the realization that I would have to wait for the sequel!

It seems the plan is for the next book to come out in the same three formats next January. This one has been nominated for a Nebula Award, and Beth Cato has apparently also written another duology and a trilogy that I will have to check out. She also has a blog called “Bready or not” (I love a good pun, I used to have a bread-baking business called “Friends in Knead”), and an Instagram page (@catocatsandcheese) featuring gardening, bread, cheese, and cats. I could definitely be friends with this person!

Fictional Food

I guess that should really be “food in fiction,” because there’s nothing fictional about the food except that it appears in a novel.

Are you one of those readers who has to ration your supply of cozy mysteries because every time the author describes some sumptuous treat in the pages of your book, your tendency is to fetch some to enjoy yourself while reading? It’s all too easy to put on a pound or two if you let fiction be your guide, and the food to which I am specifically referring on this Hallowe’en day is, of course, that treat traditional to Thisby Island, the infamous November cakes created by Maggie Stiefvater for the pages of her book The Scorpio Races.

Every October on the island of Thisby, the capaill uisce, or water horses, emerge from the sea like foam made flesh. The giant horses are a danger to anyone who comes near, being both predatory and carnivorous, but the islanders have a yearly tradition of capturing and training them to run a race along the beach on the first day of November. Winning the Scorpio Races yields both fame and substantial fortune, but the races also take many lives. Katherine (called Puck) has decided to enter her land mare in the races to earn the money to save her home, while Sean Kendrick is competing for the right to buy the water-horse stallion Corr. The two teens, both orphaned by capaill uisce, become both allies and competitors in this race for glory or death.

In the cold and damp that is a Thisby November (think Wales or Ireland climate), there is nothing more welcome than a cup of salted butter tea (thanks, I’ll stick to English Breakfast) and a hot, sweet, buttery November cake. Here is a link to the recipe, created by Maggie. They are not simple to make, nor are they cheap, but they are well worth the trouble. The description from the book:

Finn finds my left hand, opens my fingers, and puts a November cake in my palm. It oozes honey and butter, rivulets of the creamy frosting joining the honey

The Scorpio Races

in the pit of my hand.

It begs to be licked.”

Maggie Stiefvater

If your food plan doesn’t allow for such treats, at the least you can make a yearly tradition of reading The Scorpio Races, one of my favorite books by Maggie Stiefvater and perhaps soon to be one of yours as well.

Openings

Los Angeles Public Library finally let me have The Ten Thousand Doors of January, by Alix E. Harrow, a book about which I had massive anticipation after having devoured Alix Harrow’s second book, The Once and Future Witches (review here). And while that book was about spells hidden in plain sight and this book was about elusive doorways, in a real sense both books are about openings.

The 10K Doors beguiled me from almost the first page. The language was beautiful, evocative, persuasive. The story begins with a book, which is always a way to my heart. And the door theme carried me back to every beloved tale in which someone found an opening to somewhere else and was brave enough to step through it, from the classics (Alice in Wonderland, The Phantom Tollbooth, Narnia) to more recent works (Mirrorworld, Shades of Magic, Un Lun Dun), but it particularly put me in mind of Wayward Children, the stunningly original series by Seanan McGuire that portrays a group of children who have had the experience of going through a portal to the world of their dreams, only to later be ejected and left longing to return. The Ten Thousand Doors of January is the ultimate portal novel.

Like the protagonists in McGuire’s series, January Scaller is a misfit in her own life. Her childhood has been simultaneously comfortable bordering on indulgent, and immensely restrictive; while her widowed dark-skinned father travels on business for his employer, January lives a sedate, smothering life sequestered in Mr. Locke’s mansion that is filled with the artifacts and treasures her father has brought back to him from all over the world. January spends most of her young life torn between gratitude for Mr. Locke’s guardianship and patronage, and resentful that she is kept like another of his precious objects, locked up in a house with no company save for that of a repressive nursemaid/chaperone. As a person of color, January is ogled and patronized by the lily-white British society within which the wealthy Mr. Locke moves (the story begins in 1901), and she has no friends save an Italian grocery delivery boy and the enormous and fanatically loyal dog with whom he gifts her.

As a solitary child, January naturally seeks out ways to amuse herself, and becomes immersed in certain texts and books not meant for her eyes, writings that reveal a possible escape from her overweening patron. But after her father dies and Locke discovers she may have abilities he and his friends value, January must call upon all her thus-far meager resources to save herself from their plans, and also prevent the doorways she has discovered from closing forever.

Books can smell of cheap thrills or painstaking scholarship, of literary weight or unsolved mysteries. This one smelled unlike any book I’d ever held. Cinnamon and coal smoke, catacombs and loam. Damp seaside evenings and sweat-slick noontimes beneath palm fronds. It smelled as if it had been in the mail for longer than any one parcel could be, circling the world for years and accumulating layers of smells like a tramp wearing too many clothes. It smelled like adventure itself had been harvested in the wild, distilled to a fine wine, and splashed across each page.

Although the book has a somewhat slow start, and the protagonist is initially almost frustratingly passive despite her inner nature (“The will to be polite, to maintain civility and normalcy, is fearfully strong. I wonder sometimes how much evil is permitted to run unchecked simply because it would be rude to interrupt it”), the story within a story of Adelaide (Ade) and Yule Ian Scholar (Julian), who find one another when Yule crosses through a door from his home into a Kentucky wheat field, pulls you first into that world and then into the possible connections with January’s, and after that it’s total fascinated attention to the very last page.

This book is almost haunting in its sadness and yearning for the freedom of a wider world, and a longing for the ability to translate otherness into belonging. The loneliness of January, motherless and separated from a father who wants to keep her safe but believes that can’t happen if she is with him; the solitude of Ade, searching relentlessly for the door that will carry her back to Julian; the alienation of January’s friend Jane, exiled from her homeland because of a promise; all act upon the reader to provoke a desperate wish that these people will get what they want, find what they seek, and in that process make the universe a more fluid place.

Doors become more than just passageways to new experiences; they are also symbols of openness and change, qualities that January considers essential while Mr. Locke deems them threatening to existence. Stagnation is antithetical to those who wish for true freedom for everyone, while to the people in power it is an essential component in consolidating their dominance. January is one girl up against a wall of opposition, but she finds unexpected resources from her past, from her few allies, and finally from within. This story connected with my dogged belief, despite the mundanity of everyday life, that there is both magic and hope out there somewhere, if only the way can be found.

It bowled me over.