Significant relationships

I picked up The Marsh King’s Daughter, by Karen Dionne,

with the misconception that it would be a fantasy retelling of an obscure fairy tale. But although the author makes creative episodic use of the Hans Christian Andersen story of the same name by revealing it gradually in chapter headings, the tale told here is all too real.

Helena Pelletier is revealed as a former “wild child,” one of those who has been raised in the wilderness outside of society, under no one’s influence but that of her parents. Even that statement is misleading; her mother played no real role (except that of passive housekeeper and provider of meals). Her Anishinaabe nickname, given to her by her part Native American father, was Little Shadow, and Helena became, as she grew, a miniature version of him, learning all he was inclined to teach her—including a basic disdain for her weak and ineffective mother. Under his tutelage she learned to track, trap, hunt, gather, and survive in the combination of forest and marshland in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan where their cabin was situated.

The truth that she finally discovers at age 12 rocks her world and skews all her perceptions: Her father kidnapped her mother off the street when she was 14 years old, brought her to his cabin in the marsh, and held her prisoner. At age 16 she became pregnant and gave birth to Helena, who spent the next 12 years in ignorance and freedom, being raised by the victim and her captor.

The story is compellingly told in alternating chapters of present day and past tense. After eluding arrest for two years, Helena’s father spent 13 years in prison for his crimes. But now he has managed to escape, killing two guards and supposedly heading off into the heart of a wildlife refuge. But Helena, now in her late 20s and with a husband and two daughters of her own, knows him well enough to believe that this is misdirection to get the manhunt going in that area while her father will make his way to the land he knows best, part of which is now the site of Helena’s family home. She also believes that since no one knows him and his skills the way she does, she is the only one who can track him down.

Each revelation in the present day leads to a chapter about her life in the past, and as the book moves to its conclusion, the picture of what that was like grows deeper, broader, and more fascinating. This is a cat-and-mouse thriller full of suspense: Although we know from the outset that Helena’s father is “the bad guy,” the tension of seeing how her life plays out as she grows up and becomes self-aware enough to recognize him for who he is—a dangerous narcissist, a psychopath—gives agency to some truly compelling character development. The conflict experienced by Helena, who goes from idolizing her father to questioning his authority to the major revelation of his actions, followed by an uncomfortable and protracted adjustment to her new life in society, shows all the nuances of parent-child relationships and how they help and harm as children achieve adulthood. I’m so happy to finally have read a book this year that I can unequivocally endorse! Five stars from me.

One of the attractive parts of this story is the wealth of detail about the marshes and wetlands of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan in which it is set; but I should also note that there is a fair bit of detail about the trapping and killing of animals for food that may disturb some readers. I am a vegetarian for compassionate reasons and managed to get through it, but some of it was more graphic than I would have liked.

Faerie tale magic

Spinning Silver, by Naomi Novic, is so exquisite, both in the writing and in the telling, that after having spent three days reading at breakfast, lunch, and bedtime, I stayed up from 2:00 until 4:00 a.m. this morning to finish it; and when I got up at 9:00 and made my breakfast, rather than starting a new book I opened Spinning Silver

to page one and began reading again, to remind myself of all the reasons why.

I purposely used the alternate spelling of “fairy” in the title because, although this book is billed as a fairy tale retelling, it is light years away from most of those. It borrows a couple of basic concepts from “Rumpelstiltskin,” turns them completely on their heads, and goes on with a story nothing like that mean little tale. There are actual faerie in this book, but they have more to do with the fey creatures of Celtic lore than with any relatively prosaic fairy godmother from the Grimms’ tales.

I purposely used the alternate spelling of “fairy” in the title because, although this book is billed as a fairy tale retelling, it is light years away from most of those. It borrows a couple of basic concepts from “Rumpelstiltskin,” turns them completely on their heads, and goes on with a story nothing like that mean little tale. There are actual faerie in this book, but they have more to do with the fey creatures of Celtic lore than with any relatively prosaic fairy godmother from the Grimms’ tales.

This is, above all, a character-driven story, and so you have to be patient as a reader for the first little while until you are sufficiently acquainted with the three protagonists. As a readers’ advisor, I am always one to tell a reader that if they aren’t enjoying a book in the early chapters, by all means drop it and find another. I’m not saying that this book isn’t good from page one—it is. And things begin happening from fairly early in the story; but it takes about 120 pages (which is a pretty big commitment out of 480) to complete your introduction to the pivotal characters and provide some action that really moves their joint story forward in a significant way.

As a person who loves character development, that didn’t matter to me in the least, because I was so fascinated with the way the first protagonist, Miryem, morphs from a cold, hungry, desperate girl into a tough, confident one who, once she decides that she is the one who will have to take care of her family, shows no hesitation.

Miryem and her parents, the Mandelstams, are Jews living on the outskirts of their little village near the forest. Miryem’s mother’s father is a moneylender in the larger town of Vysnia, and a hugely successful one; but Miryem’s father, who decided to take up the same profession based on the dowry from his wife, is too gentle to make a living the same way. When he attempts to collect on the money he has lent, his customers jeer at him, shout racial epithets, and chase him from their doorsteps, or else make excuses that they know will touch his soft heart and cause him to give way. All around the Mandelstams, the other people in the village are benefiting from the money they have borrowed, with their investments in more livestock, better farm tools, warm clothing, and fields of crops, while the Mandelstams starve. Finally, with her mother ill and her father helpless and discouraged, Miryem decides that she will have to be the moneylender of the family and, taking up her basket, she treks from door to door insisting on her just desserts. Soon there is a new thatched roof, warm clothing, and meat in the pot, but her parents weep that she has become cold inside from this “unladylike” profession.

Meanwhile, six miles away, Wanda lives with her Da and her brothers, Sergey and Stepon. Her mother is dead, buried in the yard under a white-blossoming tree with her six miscarried baby boys, and her father is a drunkard and a wastrel who has borrowed six gold kopeks from the moneylender, more than he will ever be able to repay. When Miryem comes calling asking for payment on the debt, he reviles her and tries to drive her away. She knows that if she lets him win she will confront the same problem at every turn, so she tells him that his daughter, Wanda, may pay off his debt a half cent a day by working for her and her parents. Although Miryem believes this will be a hardship, Wanda is secretly delighted, since it gets her out of the house and away from her father’s constant abuse; so Wanda becomes a fixture in the Mandelstam household, and soon becomes the debt collector in Miryem’s stead, while Miryem pursues other business.

Finally, after an ill-advised boast by Miryem about being able to turn silver into gold attracts the attention of the king of the Staryk, who comes to her with a bargain she is unable to refuse, we meet the third leg of the stool of this story: Irina, daughter of a duke and a quarter-breed Staryk “witch” and, up to this point in life, a plain and silent girl with no expectations. But the advent of Staryk silver alters her worth in the eyes of her ambitious father, and she suddenly finds herself betrothed to the dashing Tsar Mirnatius, who is both less and a lot more than he seems, with dire effect. Although the men in the book play pivotal roles, it is this triad of women whose thoughts and actions control the progression of their layered, interwoven lives, and who end up saving the kingdom of Lithvas from powerful enemies.

The themes in this book—agency, self determination, pride, empathy, duality, the embracing of family wherever you find it—are pervasive, and poignant but also raw. Watching each protagonist rise to her challenges with ingenuity and quiet determination was a joy. And the best praise I can give is that the quality of the character development, the language, the scene-setting, everything you would want from a story like this were maintained from beginning to end. The final sentence was as satisfying as all the rest, and was the perfect ending to a gripping and entertaining tale. It’s been a long time since I read a book that I loved with as much fervor as this one. I wish I hadn’t waited so long to read it after I heard about it. I was and am thoroughly beguiled.

ADDENDUM: I must address one issue with this book that was brought up to me by a friend on Goodreads. Although the author otherwise goes out of her way to be inclusive and expansive in her representation of characters of different religious and economic status, she is not similarly sensitive when it comes to the one gay character in the book. There is a courtier who makes it obvious that he is smitten with his cousin the Tsar, and Novik has the protagonist Irina scheme to marry him off to a woman for her own political gain, and is mocking and dismissive of his true preferences, actually threatening him to get him to comply with her plan. Novik needs to recognize that gay people merit the same sensitivity of treatment as her other represented groups. She should know that bad gay representation is worse than no gay representation. Yes, it’s two pages out of 480, but it continues a precedent and a prejudice that should not be present in this jewel of a book. I’m sorry to see it here.

Another chance

If you have been a reader of the Book Adept blog for a while, you will perhaps recall my review of Diane Setterfield’s Bellman and Black, and the depth of disappointment I experienced on reading it.

It took me a while to be willing to assay another of her books, but I found the description of Once Upon A River, published in 2018, to be too enticing to resist, so I bought a copy and read it this past week. I am happy to say that it fulfilled my expectations, which included the lyrical language of her previous books but also contained a satisfying story arc, with a beginning, a middle, and an end, and resolution for the varied and mysterious characters involved.

As its title promises, the book is framed as a fairy tale, or at least is fairy tale-like. The river in question is the Thames, and the river is the central character of the book, as it affects everyone who comes in contact with it—those who live along its length, in pubs, villages, towns, and isolated huts, those who punt along in its shallows or ride its currents on barges or private yachts, and those who end up drowned in its depths.

“They sat on the bank. It was better to tell such stories close to the river than in a drawing room. Words accumulate indoors, trapped by walls and ceilings. The weight of what has been said

can lie heavily on what might yet be said and suffocate it. By the river the air carries the story on a journey: one sentence drifts away and makes room for the next.”

This is the story of three children, and the impact of their disappearances (and possible reappearance) on the people close to them, as well as on the inhabitants of one small town who are caught up by chance in the events that restore one of them to life.

Amelia is the daughter of the Vaughans, a wealthy couple, who gladly pay the ransom when she is boldly kidnapped right out of her bed, but don’t receive her back again after their payment. Alice is the child of a desperate mother who, abandoned by her ne’er-do-well lover and unable to care for herself or her little girl, ends it all in a jump from a bridge above the roiling waters of the Thames, after first dropping her daughter in to drown. And Ann is the sister of Lily, a poor unfortunate who makes her way by keeping house for the local parson, but who isolates herself in a hovel by the river because she is making amends for something dreadful she did as a child that lost Ann to her forever.

Along the borders of this world lie others. There are places you can cross. This is one such place.

On the night of the winter solstice, the regulars at The Swan, an ancient inn at Radcot along the Thames, are occupied in their usual pursuit of telling stories. The door bursts open to admit a stranger, badly wounded and scarcely able to keep to his feet. He is carrying what everyone present at first identifies as a doll or a puppet, but after calling for the local nurse to examine and treat his injuries, someone realizes that it is actually a child, a little girl, already dead.

Hours later, however, the girl stirs, takes a breath, and comes back to life. No one can account for her previous deathlike state, but all are happy to have a child returned to life, against all odds.

But whose child is she? Helena Vaughan, who has been deranged with grief over her daughter’s kidnapping, is ready to embrace her as the missing Amelia, even though two years have passed. Someone else recognizes her as Alice, the granddaughter of another local family, who would be happy to welcome her although she is the love child of their wayward son. And Lily is convinced her sister Ann has returned to life. The girl herself is mute and unable to answer the questions of who she is, where she came from, and to whom she belongs. Both the principals and the villagers who were present at her dramatic denouement involve themselves in theories and possible solutions, and under all runs a dark current of deceit and, some would say, evil.

This is a compelling, thoughtful, and engaging read. The ins and outs, the possibilities, the theories and discussions encompass not only the fate of one small child but the bigger picture, the issues of life and death—how much they are worth, how they arrive, how they depart, what is the best way to pursue them. The discussion includes the new theories of a man called Darwin, who posits that man comes from water and from animals and is therefore related to and also responsible for all life, not just that of humankind. The historical details included in the occupations of some of the characters are engrossing (farmer, charlatan, photographer). And all of it is entertwined with the constant presence of the river, the giver of life and death to so many who move along its banks and in its depths. The fairy tale quality is palpable but the archetypal nature of fairy tales doesn’t dominate the story, which is individual and unique.

I think perhaps Diane Setterfield has, with this book, surpassed The Thirteenth Tale, as wonderful as that book was. But it’s hard to compare them, for although they both have literary language and a timeless feel, they are completely different stories, sharing only the theme of magical realism. Now that I have regained my confidence in her work, perhaps I will return to that book for another look—it’s been a decade since I read it.

Lost

Someone recommended Jane Harper to me as an author I might enjoy, so on my last virtual library visit, I downloaded The Lost Man to my Kindle. I forgot it was there and read other things, then realized I only had seven days left before it disappeared back into the library catalogue, so I put aside the Christmas-themed stuff for a minute and started it at 3 a.m. on Monday.

To quote another reviewer on Goodreads, this is less a novel and more an experience in which you lose yourself. And when you read it unencumbered by expectations, the power of its prose jumps out at you and grabs every bit of your attention.

The landscape, the Queensland (Australia) outback, is the most powerful character in the story. The landscape pares people down into either the essence or the caricature of themselves. Setting a mystery there is like creating a locked room puzzle (once you get in, there appears to be no way out), except that the room is an endless, airless, boiling plain of sand. The setting has dictated the style and pacing—spare, dry, concentrated.

The characters, three brothers, run livestock on land that, while adjacent to each other’s holdings, is hours apart in travel time, from each other and from “town.” Nathan Bright, the eldest and the protagonist, works alone and lives alone on his land (a backhanded gift from his former father-in-law), a scandal in his past making him a pariah with everyone but his family, and uncomfortable even with them. Divorced and bitterly intent on prying some form of joint custody of his son, Xander, from his ex-wife, Nathan is inturned and enigmatic. Cameron, the middle son, a “hail fellow well met” type, and “Bub,” the youngest brother, a bit lost in the shuffle and wishing for other options, live and work together on their father’s former holdings, with Cameron’s wife and two children, the boys’ widowed mother, and various stockmen and itinerant workers.

The characters, three brothers, run livestock on land that, while adjacent to each other’s holdings, is hours apart in travel time, from each other and from “town.” Nathan Bright, the eldest and the protagonist, works alone and lives alone on his land (a backhanded gift from his former father-in-law), a scandal in his past making him a pariah with everyone but his family, and uncomfortable even with them. Divorced and bitterly intent on prying some form of joint custody of his son, Xander, from his ex-wife, Nathan is inturned and enigmatic. Cameron, the middle son, a “hail fellow well met” type, and “Bub,” the youngest brother, a bit lost in the shuffle and wishing for other options, live and work together on their father’s former holdings, with Cameron’s wife and two children, the boys’ widowed mother, and various stockmen and itinerant workers.

At the beginning of the story, there is a small gathering at the stockman’s grave, a landmark headstone out in the middle of nowhere, so old that no one remembers who is buried there. Various legends remain about this eerie place, and it’s about to acquire one more: Cameron’s body has just been discovered in the slight shade cast by the stone.

Questions abound: How did he get there? Something had been troubling him—did he choose to meet his death by this unpleasant method? This is the premise of local law enforcement, and also of most of those who knew him…because if he didn’t, then the incredible isolation in which these people live leaves room for only a few suspects. The questions begin to prey on Nathan’s mind….

The mood and the tone of this book fascinated me. The characters remain enigmas for much of the story, their demeanors an exercise in taciturnity. Even the children are opaque. Likewise, the stark factors of living in the outback—reminding yourself to drink 10 times a day, attending the School of the Air via radio because the closest “local” school is 20 hours away in Brisbane, never leaving the property without noting down your destination and the expected time of return so a search party can be sent out if you miss your mark…all speak to a daily tension already so high that adding any sort of drama to it could spark a wildfire.

If you enjoy inhabiting an environment nothing like your own and learning what kinds of people are challenged by it to make a life there, this book will pull you in. If you are fascinated by the interplay of emotions between characters who have known each other forever and yet now doubt they know anything at all, this book will keep you guessing. Slow pacing and immaculate plotting give you questions and doubts just as the characters arrive at those same thoughts. It’s an emotionally charged but quietly told story that is probably my favorite read of 2019.

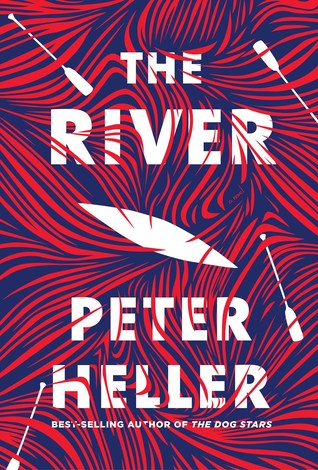

READERS’ ADVISORY NOTES: I’m trying to dredge up from my subconscious some other books that might share the appeals of this one. Perhaps The Road, by Cormac McCarthy, although it is such a stylized kind of work compared to this…. The River, by Peter Heller, has certain similarities. Maybe The Round House, by Louise Erdrich? or Bluebird Bluebird, by Attica Locke? The Lost Man gives me sort of the same feeling as reading “King Lear,” with the twisted family dynamics, the ugly lies and truths, the suspicions and doubts and manipulations.

Bellman & Black

As I mentioned in my Hallowe’en/ Samhain post,

I have been reading Bellman & Black, by Diane Setterfield. I anticipated enjoying this book greatly, based on my experience of The Thirteenth Tale. Unfortunately, that anticipation was misplaced. In most book reviews, I hesitate to give away too much, but in this instance it doesn’t make a difference in your experience of the story. I will reserve the ending.

You get the highlights in the book description on the dust cover. When he is a boy, William has three other friends—all born in the same month of the same year—with whom he runs and plays. As boys did in Victorian England, one of their pastimes is to shoot at things with slingshots. One day William lines up an impossible shot aimed at an immature rook perched in a tree and, against all odds, he hits and kills it. Then there are ominous pronouncements about how rooks never forget, rooks are smart, rooks will avoid you if they perceive you as evil, etc.

Drawing of slingshot © 2019 courtesy of Mishu Bogan

William grows up, forgets about this incident, is taken on at his uncle’s mill, and discovers that he has an uncanny sense of how to better a business. He revamps everything about the mill, endearing himself to both his uncle and the workers. When his uncle dies, the heir, his cousin Charles, an amateur painter and art collector who prefers to spend his time in Italy, lets William get on with running the business for a large share of the profits. He does well, takes a wife, has four children, and then…everyone starts to die.

After his uncle, it’s the three boys with whom he grew up, who drop one by one for various reasons; then a fever comes to town and takes away all of his family but one. And at each funeral, he sees the same man, dressed in black, hovering around the churchyard, giving him significant looks, winks and smiles, but somehow eluding him whenever William tries to engage the man. Finally, at the last funeral, William, desperate to save his daughter Dora, talks to the man, and seems to think they have struck a deal to keep Bellman’s one remaining child alive. From this man (supposedly), Bellman gets the impetus to open a large emporium in London that deals with every aspect of the death industry, from coffins to mourning clothes to stationery to gravestones. It is to be a magnificent edifice, five stories high and boasting its own live-in staff of seamstresses, and Bellman regards the elusive Mr. Black (as William has christened him) as a sleeping partner.

End of part one. Although it’s taken a long time (and a whole lot of details about running the mill) to get there, you’re thinking oh, this is where William Bellman starts interacting with and attempting to placate Mr. Black, who is somehow the nemesis who has brought all these deaths into William Bellman’s life. Hmmm.

End of part one. Although it’s taken a long time (and a whole lot of details about running the mill) to get there, you’re thinking oh, this is where William Bellman starts interacting with and attempting to placate Mr. Black, who is somehow the nemesis who has brought all these deaths into William Bellman’s life. Hmmm.

This is supposed to be a ghost story. There are no ghosts. Bellman is indeed haunted—by his numerous dead, and by Mr. Black—but he manages not to realize it, because he keeps himself so frantic with establishing and running his businesses that he evades every thought in his head not involved with inventories, displays, products, sales figures, and improvements. You keep reading, and waiting. You get more tidbits of information about rooks. You get more descriptions of William’s evasive actions that keep his business thriving but deprive him of all self-knowledge. You finally get to the end, and…what?!

I don’t know what to say about this book. It is beautifully written, and it is obviously about life and death and grief, and yet its main character does not grieve, scarcely acknowledges either the living or the dead, and manages to live in a psychological wasteland of his own contriving. You could call it Victorian gothic, or psychological fiction, or literary fiction, but in the end, it’s 300+ pages of description about the processes, not the thoughts or feelings, of one man’s life. And while I found the technical details of both the milling process from shearing to finished dyed cloth, and even the conception and set-up of the Bellman & Black emporium to be fascinating from an historical perspective, it’s not enough to carry the rest. Bellman is basically running from both death and grief, but it isn’t particularly ominous, or powerful, or poignant, or cathartic. It is lyrical, but it is slow, and its conclusion, for me, was incredibly disappointing and somewhat vague. I can’t say it was a bad book…but I honestly couldn’t recommend it. Which makes me sad.

In my previous review, I mentioned another book with the same feel as this one, in terms of the lyrical narrative and kind of weird premise. The book is Far Far Away, by Tom McNeal. In that story the protagonist, Jeremy Johnson Johnson (his parents both had the same last name) is guided in life by a voice in his head. It is, specifically, the voice of Jacob Grimm, one of the two renowned Brothers Grimm who collected the fairy tales. Jacob watches over Jeremy, protecting him from an unknown dark evil that is being whispered about in the space between this world and the next and apparently threatens him. But when town troublemaker Ginger Boultinghouse takes an interest in Jeremy, a grim (pardon the pun) set of events is put into motion. Many fairy tales don’t have happy endings…

This was such a strange, fanciful, weird, interesting book. Because it’s mostly told from the viewpoint of Jacob Grimm, the narration has an old-fashioned quality that makes you feel like you’re in a fairy tale taking place in the 1800s, but it is in fact set in a 20th-century small town, with electricity, television, and all the amenities. It’s an odd mix, but it works, and the story has an arc with a satisfying ending. I offer it as an alternative.

This was such a strange, fanciful, weird, interesting book. Because it’s mostly told from the viewpoint of Jacob Grimm, the narration has an old-fashioned quality that makes you feel like you’re in a fairy tale taking place in the 1800s, but it is in fact set in a 20th-century small town, with electricity, television, and all the amenities. It’s an odd mix, but it works, and the story has an arc with a satisfying ending. I offer it as an alternative.

New from Heller

I never bypass the chance to read a novel by Peter Heller. I love that I never know what to expect—each book is so different from the one before, but all are gripping; his prose is both spare and lush in its evocations; and on top of that, the guy can tell a story. Once having read both The Painter and The Dog Stars, I would have been hard pressed to choose a favorite between them, and although I liked Celine less, it was, again, such a departure from previous works that both its characters and its mystery intrigued me.

His new book, The River, is similarly powerful. The sense of uneasiness evoked from the very first page builds to a cascade of climactic moments, each overpowering the previous one, until you wash into the ebb tide of the epilogue and realize you’ve been holding your breath for a good part of the book.

His new book, The River, is similarly powerful. The sense of uneasiness evoked from the very first page builds to a cascade of climactic moments, each overpowering the previous one, until you wash into the ebb tide of the epilogue and realize you’ve been holding your breath for a good part of the book.

Two college friends, Dartmouth classmates Jack and Wynn, are taking a much-dreamed-of trip together, setting aside a few weeks to canoe a series of lakes into a northern-flowing river up into Canada. Jack, who was raised on a ranch in Colorado, is the more experienced of the two at camping and hunting, but Wynn, a gentle giant from rural Vermont, has his share of skills. They plan a leisurely trip of trout fishing, blueberry picking, and a slow trek through a route that alternates between smooth, flat water idyllic for paddling and rapids that must either be run or portaged around.

All of this changes one afternoon halfway through the trip, when the two climb a hill and see the glow of a massive forest fire about 25 miles off but clearly headed directly across their path. The lakes up until now have been completely empty of humans, and the two boys have enjoyed the cry of the loons and the spectacle of moose, bear, and other wildlife, but as they paddle upstream with new urgency, they encounter first a pair of men, drunk on whiskey and lolling in their campsite with no awareness of their peril, and then, as fog drops down and obscures the shore, they hear the voices of a man and woman, arguing passionately, their voices bouncing across the water. They warn the men about the fire, but can’t catch a glimpse of the contentious couple, and paddle on to their next campsite.

The next day, burdened with a sense of guilt for not searching harder, Jack and Wynn agree to turn back and warn the couple, if they can be found. This turns out to be a fateful decision that burdens them for the rest of their trip with unexpected responsibilities, dangers, and crises over and above the dreaded wildfire, which approaches ever closer.

Heller always delivers on atmosphere, and even if you have never camped out, paddled a canoe, or caught a fish, you are right there with his characters on the bank of the lakes and river, looking at the stars, watching the raptors in their nests at the tops of the tallest trees, or reeling in a line with a brown trout on the hook. The reader also gets quickly inside the heads of both protagonists, as well as tapping into the quiet and solid friendship between the two, which nonetheless becomes strained as events ramp up to catastrophe and their differing temperaments emerge.

As with his other books, I read this one in a day and a half, only deterred from one continuous sit-down by a traitorously depleted battery in my Kindle. In an interview for Bookpage, Heller said that he writes…

“…a thousand words a day, every day, and I always stop in the middle of a scene or a compelling train of thought. Most writers I know write through a scene. But if you think about it, that’s stopping at a transition, a double-return, white space. That’s what you face the next morning; it’s almost like starting the book fresh. If you stop in the middle, you can’t wait to continue the next day.”

That same sense of urgency pervades me as I read any of his books.

Books about the queen

Although I included The Uncommon Reader, by Alan Bennett, in a previous list of “books about books,” I hadn’t actually had the pleasure of reading it.

Although I included The Uncommon Reader, by Alan Bennett, in a previous list of “books about books,” I hadn’t actually had the pleasure of reading it.

I finally got around to it recently, and felt I had to follow up with a little more detail about this delightful story.

A certain generation of us were raised with a particular consciousness of England’s royal family, because the abdication of Edward VIII from the throne (in favor of marrying a divorceé, Wallis Simpson, which simply wasn’t “done” at the time) catapulted his brother, Albert, to the throne as George VI. The key ingredient to this story for girls, however, was that George VI had two daughters, Elizabeth (the next heir) and Margaret Rose, who were instantly in the limelight, and we were fascinated with their every move—their dress, their hobbies, their education, their pets….

Already predisposed towards the love of princesses,

Already predisposed towards the love of princesses,

I came to know about the real ones through a book my mother bought me, called The Little Princesses, by Marion Crawford. The initial events took place in the 1930s when “Lilibet” and Margaret were five and two years old, respectively (well before my time), but the book, written by the princesses’ long-time governess, “Crawfie” (as she was nicknamed by Elizabeth), was published in the 1950s, and it crossed my path when I was seven—able to read its grown-up text but probably not able to understand some of it until re-reads years later. I was nonetheless fascinated with the whole story, and particularly the photographs of the princesses and their governess, dogs, ponies, and so on that were included in the book, and over which I pored at length.

The book explores the inner life of the royal family from the girls’ childhood up through Elizabeth’s wedding and the birth of her son, Prince Charles. It does so lovingly and without a hint of scandal or any lack of respect, but Crawford was nonetheless banned from the family (and from her employment) for writing it, despite her claim of having been given permission to do so. The rumor is that the Queen Mother felt the intimacy of the narrative would detract from the mystique of the holder of the throne.

Cut to the recent past, when Queen Elizabeth’s early reign has been explored by the Netflix series “The Crown.” In it, Elizabeth is portrayed as deeply uncertain and vulnerable on the inside but formal, traditional, and almost staid in her mannerisms (particularly for a young woman) on the outside—ever conscious of her image and her duty to uphold a certain appearance. For those who had read the account by Crawford of her formative years, the portrayal was spot on, and continued a sense of exactly who Elizabeth II is in the world (even to the uncanny similarity of appearance between the actress, Claire Foy, and the young queen).

Cut to the recent past, when Queen Elizabeth’s early reign has been explored by the Netflix series “The Crown.” In it, Elizabeth is portrayed as deeply uncertain and vulnerable on the inside but formal, traditional, and almost staid in her mannerisms (particularly for a young woman) on the outside—ever conscious of her image and her duty to uphold a certain appearance. For those who had read the account by Crawford of her formative years, the portrayal was spot on, and continued a sense of exactly who Elizabeth II is in the world (even to the uncanny similarity of appearance between the actress, Claire Foy, and the young queen).

I preface my comments about The Uncommon Reader with all this simply to say that Alan Bennett also has an extraordinary grasp of both the woman and the office, and portrays her as a somewhat elderly woman who has pursued exactly the life Elizabeth II has lived, only to find that something has been missing that, upon its discovery, changes everything.

A short synopsis of the book: Queen Elizabeth, wandering outdoors in search of her beloved corgis, stumbles upon a bookmobile near the palace. She feels compelled by good manners to check out a book, which she struggles through, returns, and feels compelled to take out another. But this one she enjoys! This behavior is out of character for the Queen, who has previously allowed herself few hobbies or interests that express a preference for anything, and now here she is, preferring books, which habit begins to influence the person she is and how she reigns and interacts with her subjects. Not everyone approves, however; politicians and staff collaborate to steer her away from this selfish, isolating, alienating addiction!

In his tiny volume (shown here in my gargantuan hand just to convey size and scale), Bennett absolutely nails the personality, the inner thoughts, and the outer habits of the Queen, along with the judgments and expectations of those intimates of her court who are always on the lookout for aberrant behavior from their monarch, with the desire to neatly nip it in the bud. But Elizabeth isn’t going to be ruled by their expectations (after all, who is the queen here?) and quietly pursues her new hobby to an astonishing and humorous end. If you are a person who loves books about books, and you also have a sneaking fascination with England’s monarchy, don’t miss out reading this charming but also revelatory and even mildly subversive novella.

In his tiny volume (shown here in my gargantuan hand just to convey size and scale), Bennett absolutely nails the personality, the inner thoughts, and the outer habits of the Queen, along with the judgments and expectations of those intimates of her court who are always on the lookout for aberrant behavior from their monarch, with the desire to neatly nip it in the bud. But Elizabeth isn’t going to be ruled by their expectations (after all, who is the queen here?) and quietly pursues her new hobby to an astonishing and humorous end. If you are a person who loves books about books, and you also have a sneaking fascination with England’s monarchy, don’t miss out reading this charming but also revelatory and even mildly subversive novella.

Morton does write with a certain formulaic reliability: Each of her books contains some kind of perpetuating event that sends a person from the present day searching back into the past, whether it’s their own, that of a mother, aunt, or grandmother, or the history of someone who has at some point become significant in their lives. Most palpable in all her books is the sense of place—as focused as she is on character development and interaction, those characters operate from within a distinctive location—usually an old house, a garden, a bend in the river near a country town—and without that place, the lives and events about which the story turns would be greatly diminished.

Morton does write with a certain formulaic reliability: Each of her books contains some kind of perpetuating event that sends a person from the present day searching back into the past, whether it’s their own, that of a mother, aunt, or grandmother, or the history of someone who has at some point become significant in their lives. Most palpable in all her books is the sense of place—as focused as she is on character development and interaction, those characters operate from within a distinctive location—usually an old house, a garden, a bend in the river near a country town—and without that place, the lives and events about which the story turns would be greatly diminished.

If I didn’t know better, I would believe that Kate Morton has found some incantation or charm, during all her researching, that has interrupted the aging process; she has both a degree and a masters, acted on the stage for a while before settling down to write, has a husband and three sons, and has written six books, with either two- or three-year intervals between the publication of each, and yet in her pictures and videos she looks like she’s about 30 years old. I’m hoping that the sole secret is that creative expression keeps one young!

If I didn’t know better, I would believe that Kate Morton has found some incantation or charm, during all her researching, that has interrupted the aging process; she has both a degree and a masters, acted on the stage for a while before settling down to write, has a husband and three sons, and has written six books, with either two- or three-year intervals between the publication of each, and yet in her pictures and videos she looks like she’s about 30 years old. I’m hoping that the sole secret is that creative expression keeps one young!